Mention Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and some of us instantly, tragically, get an earworm. Especially if you grew up on Zeffirelli’s 1968 film version. (Pipe in the love theme with weepy violins, soaring appassionato.)

But Joshua Castille, who assumes the heavy mantle of Romeo for Endangered Species Theatre Project’s production in this summer’s Frederick Shakespeare Festival, has no such point of reference. Nor has he been subjected to Leo DiCaprio’s lazy twang as a mawkish, brash Romeo in Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 MTV-style adaptation.

As a Deaf actor, Castille must summon all the passion and poetry of Romeo’s serenades from within.

He more than delivers, attests Christine Mosere, director of this production and founder of the regional theater troupe, which goes by the shorthand ESP.

“Of course, there are lines we had to reinterpret,” she said. “There’s a line about Romeo hearing the lark. Well, Romeo’s Deaf; he’s not going to hear the lark.”

Castille is a Broadway veteran, having played Ernst in Deaf West Theatre’s 2015–16 Spring Awakening, which was performed simultaneously in English and American Sign Language. “Josh has just been a dream to work with,” Mosere said. “I wouldn’t be doing this if I didn’t have somebody of Josh’s caliber.”

As in Spring Awakening, Castille is paired with a hearing actor, Joe Mucciolo, who voices the role of Romeo. Assistant Director Neil Sprouse is a Deaf artist in charge of the sign language direction, and another Deaf actor plays the friar, with a shadow actor onstage. And Mosere, who is not fluent in ASL, has an interpretation team, Patrick and Alecia Cole, to help during rehearsals.

Part of ESP’s mission is to spotlight forgotten works and “increase representation of historically excluded artists,” Mosere said. The Maryland School for the Deaf has a campus in Frederick, and “we have a thriving interpretation community here, but you don’t really see Deaf artists on stage,” she said. Because a tragic misunderstanding is at the heart of this tragedy, she conceived this production, designed for mixed hearing and Deaf audiences, as a way to bridge communication barriers — much in the way “love conquers all.”

Gender equality is also a goal. “The largest underrepresented class in theater, especially in classical theater, is older women,” Mosere said. “They’re the true endangered species of theater.” In this production, the prince is a duchess; Tybalt, Juliet’s impetuous cousin, is female; and Mercutio, Romeo’s best friend, is played by a nonbinary actor.

DC Theater Arts chatted with Mosere this week as a prelude to Friday’s opening.

What drew you to this project?

Christine Mosere: I have always wanted to direct Romeo and Juliet because, having seen numerous productions throughout my life, I always feel it’s missing the urgency, the pace of the boom, boom, boom! Shakespeare wrote this three-hour play but said it’s a two-hour show. Of course, ours is not three hours, we had to make cuts. But I’ve never seen what I see as the energy of the show played out — and I’ve seen amazing performances, so it’s not a judgment, it’s just that another director saw it differently. Another thing I haven’t seen much in other productions is enough hate. Although it’s a love story, the hate between the Montague and Capulet families must be well presented. If the hate isn’t deep, you don’t understand why Romeo and Juliet didn’t find another solution to their predicament.

Why the urgency now?

This beautiful play is more timely now than ever because we feel like a country divided. And there’s a generational divide as well. That’s what I love about this show: you see more than one generation on stage in significant roles.

I understand your production timeline created some behind-the-scenes urgency as well.

Yes, Actors’ Equity didn’t release actors until after July 7, and Josh didn’t come in until July 11. We were originally planning an August 15 to 30 run, but collaborating with Hood College [providing the outdoor venue] meant we had to shift the show earlier. It’s obviously easier for the campus if it’s the first two weeks of the month, before all the students arrive.

How about the monkey wrench of COVID? Did you rely on Zoom?

We held auditions by Zoom. In some ways, it’s delicious, because you don’t know how tall somebody is next to somebody else. You could just pay attention to their acting and get the best cast available. I wasn’t judging on height, because normally, subconsciously, you do judge on those things. Breaking stereotyping and casting is so important to me. I love casting a taller woman with a shorter guy, or a female love interest who is a little older than the male love interest, visually — I don’t care how old they actually are.

When auditioning for the hearing Romeo, the goal was for Romeo to be one voice, someone to be Romeo’s inner voice. When playing back those auditions, I’d close my eyes, just to focus on the sound. Josh and Joe have such great chemistry. As do Josh and his Juliet [Surasree Das]; their chemistry is off the charts … and that is just luck.

How do the Deaf and hearing Romeos relate on stage?

There’s kind of a theme developing in which Joe, the “inner voice,” will move much closer to Josh when Romeo’s depressed, and a bit farther away when he’s happy. It’s magical to watch.

Besides casting and pacing, what freshness do you bring to this production?

There’s no such thing as an original idea with Shakespeare, right? “Nothing new under the sun.” But in the scene when Juliet finds out Romeo is banished, and then the next scene when Romeo himself learns he’s banished … it’s Juliet with the nurse, and then Romeo with the friar, right? Well, those scenes are really happening at the same time. So, I thought, shouldn’t the audience see it happening at the same time? I put it together in such a way — and we had to tweak it a couple of times to make sure there was enough on this side or that — to create a back-and-forth feel, so people can see how they’re reacting at similar times. Now I can’t guarantee that’s not something I read about before trying. But it popped into my head as I was reading the script: How can we give the audience that simultaneous experience?

Have you toyed with the time period or setting?

I wanted to keep it in the time period, but because of COVID, we needed to have flexibility. In keeping with Equity rules during the planning process, we were restricted to one costume because nobody was able to help actors put it on or take it off. So, I thought, let’s make it a little more abstract. It still has a Renaissance feel, but we’re not being specific. I like that, because it’s really an abstract show, anyway — basically “a long time ago.”

What are some of your favorite lines or scenes from this play?

It’s so stereotypical to say it: the balcony scene. Although seeing it with a Deaf Romeo and a hearing Juliet, it’s really powerful. I enjoy watching that every time. One thing that was so fun for me was discussing with the actors: When do they actually understand each other, and when don’t they? Because that scene is about the delirium of falling in love, you don’t need the other person to understand all the lines. And that’s where we went through the script and said, OK, there’s more freedom on this line, if you two aren’t clear with each other, because of whatever the response is, then the exchange works even without that line. We delved into things like that.

Also the back-and-forth banishment scene I very much enjoy because Juliet first thinks, when the nurse comes in, that they’re talking about Romeo being dead, when they’re really talking about Tybalt. And that was an interesting thing in our production, because Tybalt is played by a female actor. The original line is, “He’s dead. He’s dead. He’s dead.” And everybody usually understands why Juliet thinks they’re talking about Romeo instead. But when Tybalt is a female, we had to have a conversation with the actors — and I have quite a few actors in this play who like to talk it out: “Let’s have a moment. Let’s figure this out.” So, Gillian [Shelly] changed it to: “Is Dead. Is dead,” explaining, “It’s like, I can’t even get the name out.” And I said, I love it! You can’t even speak the name Tybalt because you love him, or her, so much. Some people might think she’s still saying “he’s dead,” because it sounds similar, but we’ve maintained the integrity of the work. And since Juliet had just asked a question about Romeo, it’s still clear why she thinks the nurse is talking about Romeo.

Suicide occurs 13 times in Shakespeare’s plays out of the approximately 39 he wrote, and most famously in this one. Given the protagonists are young and today’s suicide rates are alarmingly high, especially among our youth, do you ever worry about romanticizing suicide?

Of course, that’s an important conversation to have, a definite concern. And especially with today’s sensibilities, we really want to be aware of mental health issues. I did a show entirely on mental health, which I helped devise for SHIP of Frederick County, the Student Homelessness Initiative Partnership. We did three months of improv with people in the community who had some form of mental illness who wanted to be part of it. It was fascinating. We put together a show with a lot of information packed in. That’s where I learned, for one thing, how we shouldn’t say “he’s bipolar” or “she’s bipolar” but that they have this condition. After all, we never say to somebody: “You’re cancer.” It was also where I discovered the term “died by suicide” and not “committed” suicide, which involves a judgment.… So, going into this, I knew we had to put the suicide prevention hotline in the program. You do think about it. I’m grateful, though, that everyone coming to see this show knows how it ends. They’re prepared, rather than having the shock.

What’s next for you after the Shakespeare festival?

Sleep.

[Seriously] Depending on how the pandemic and winter goes, I think we’re just going back to our roots, doing actively staged readings of forgotten plays by female playwrights — plays from the 1870s to 1930s–’40s. There was some fantastic stuff written by women playwrights that nobody knows about. One of them, Rachel Crothers, had a play on Broadway every year for, like, 30 years, from 1907 to 1937. They were more popular than [George S.] Kaufman and [Moss] Hart, and nobody has heard of them, and our fans love them.

Also, we got shut down when we were in the middle of rehearsals for a stage adaptation of The Awakening by Kate Chopin — and it has opera and jazz — and we want to bring that back.

On Twitter, you describe yourself as a writer, director, and social activist. How do you apply that last role to your work in theater?

I lived and worked in New York City for 18 years. And, you know, back in the ’80s and ’90s the AIDS epidemic really hit theaters like nobody’s business. You would go to a rehearsal, and suddenly your director was gone. I was super young and it was a devastating time. That impacted me, to realize there was not enough being done, even with the nonprofit ACT UP around. That helped transform me into what I call a social justice warrior. Oh, I fail plenty of times, I don’t want to pretend I don’t. But I’m learning all the time. For me, being a social justice advocate means I’m willing to admit when I’m wrong. I was raised in a place of privilege. So, if somebody calls me out on something, a subconscious phobia or bias, I try not for my first instinct to be, “What are you talking about? Me?!” My reaction should be to say, “Well, why not me?” I was raised in this society, so how would I not be affected? Even when I was young, my mom used to say, I just gave away my lunch money; we weren’t rich. But I used to give it to somebody who didn’t have anything, because I got to eat breakfast that morning. I was worried about them. I just thought it wasn’t fair.

Is that why you don’t charge admission for your shows?

I’m kind of an extremist, but I feel theater should be free. All of our shows are pay-what-you-can, only — all of them. Theater is supposed to be accessible, and a production company needs donations either way. But we’re a nonprofit, so part of our job is to write grants and have people fund the work so that nobody has to come only on a Thursday night if they don’t have money — what if they’re busy that Thursday night? They can come any night they want and pay whatever they can. We always have a zero price.

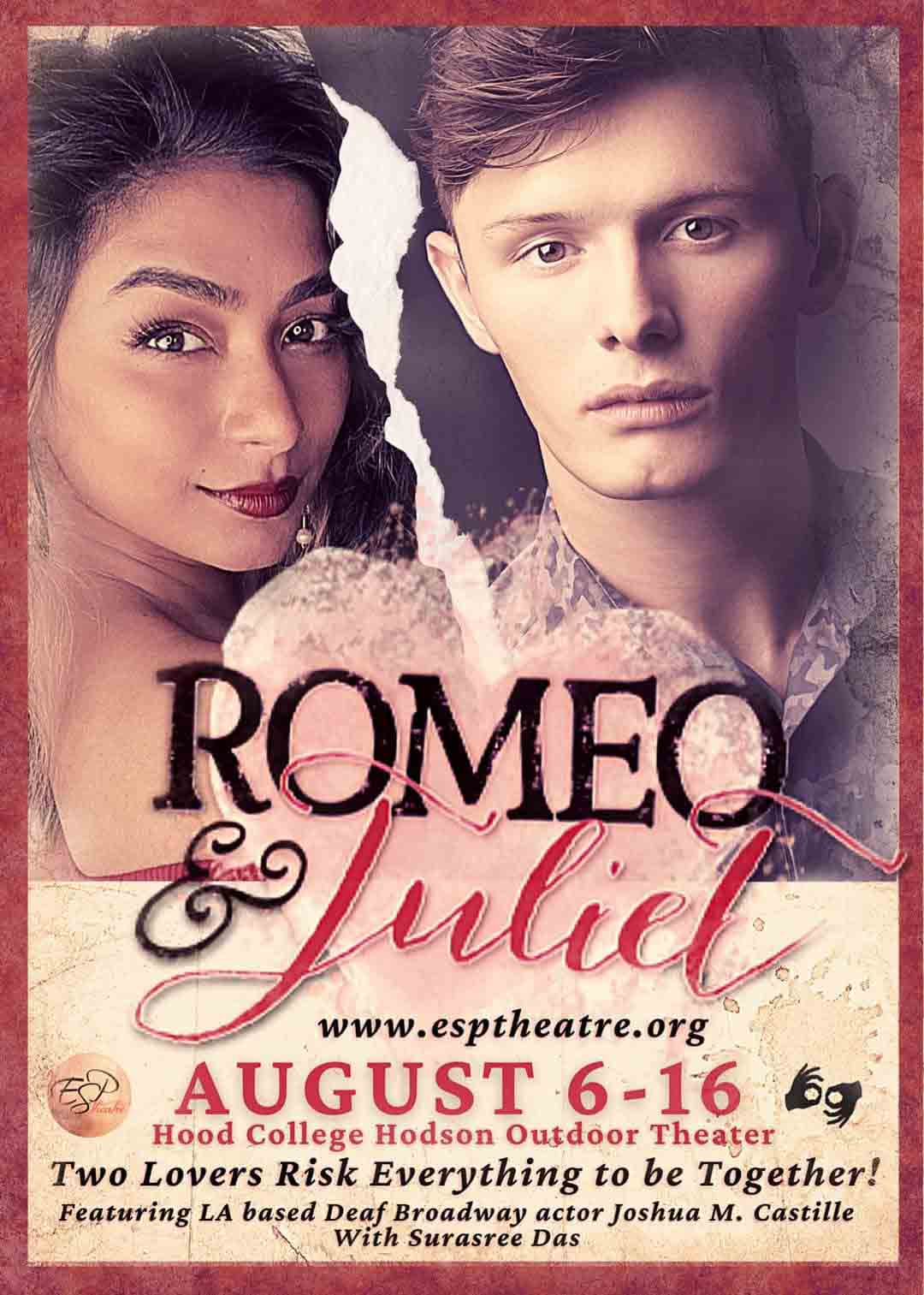

Romeo and Juliet — directed by Christine Mosere with assistant direction by Deaf artist Neil Sprouse — stars Deaf actor Joshua M. Castille as Romeo and Surasree Das as Juliet with a cast of 15 including Deaf actor Jules Dameron as the Friar, and Greta Boeringer, Jeffrey Fleming, Kailey Azure Green, Anika Harden, Marina Jansen, Stephen Kime, Charlotte Leembruggen, Mallory Leembruggen, Robert Leembruggen, Sarah Leembruggen, Darren Marquardt, Joe Mucciolo, Mallory Shear, Gillian Shelly, Daniel Summerstay, Jacob Utes, and Mani Yangilmau.