Too many Shakespeare reinventions hang on costume overhauls or time travel. But Endangered Species (theatre) Project’s Romeo and Juliet is not your garden-variety redo. This ambitious gender-bending, mind-bending treat puts patrons at the center of the re-interpretation. Designed for Deaf and hearing audiences to partake together, with complete parity through simultaneous voicing and signing, it’s a feast for the eyes and ears.

Deciding where to look, though — there’s the rub. This show is the crowning jewel of the Frederick Shakespeare Festival for good reason: It’s festive! Take the frolicsome ensemble players, who stretch their skills by signing (and fencing and dancing). Or train your eyes on two of the hardest-working ASL interpreters in town, Patrick and Alecia Cole, who don’t sit in the pit on stools telescoping lines for one small swatch of audience. Instead, they rightfully share the stage, exhaustively popping up as every character like seasoned “act-a-moles.” (Also on opening night, one leg of the set’s platform gave way, and a quick-thinking crew member joined the melee, displaying improvisational skills to make repairs without pausing the play.)

It’s a tempered three-ring circus. Even the love scenes, at first blush, threaten to form love triangles: Romeo, Juliet … plus Shadow Romeo Joe Mucciolo.

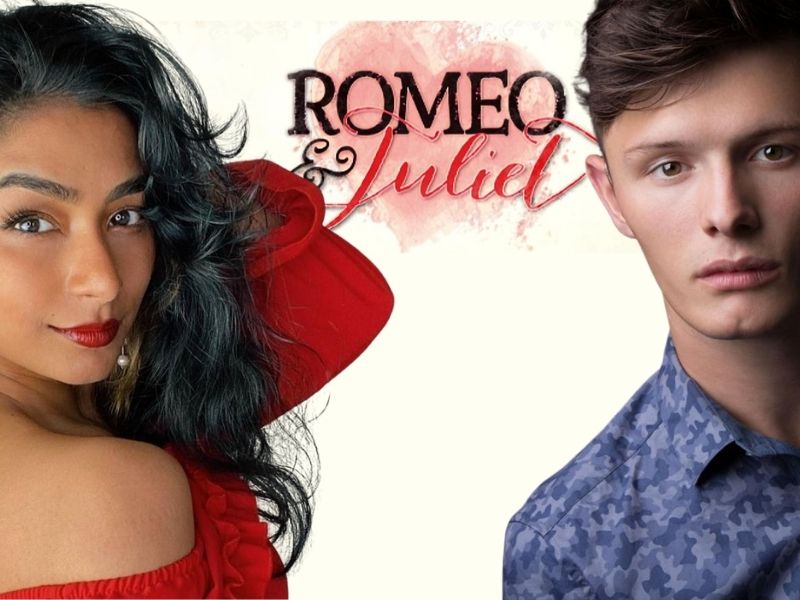

But I’m here to help. Fix your eyes, peasants, on one transfixing Romeo. It would be enough for Deaf actor Joshua M. Castille to wow with mad gesticulations and limber body language. Yet it’s his audible exhales, chest-thumping and slaps, sighs, screams, and sobs that breathe new life into this play’s DNA.

ESP’s other notable twist is the shattering of gender barriers in casting. Part of artistic director Christine Mosere’s mission is to elevate women on stage, and the results are liberating. As a female Tybalt, Juliet’s cousin who raises a family feud into a cascade of fatalities, Mallory Shear is more menacing — and memorable — than any male counterpart. Friar Lawrence, who devises the scheme for Juliet to feign death so she may escape with her Romeo, is not a bumbling opportunist when seen as a woman of the cloth. Deaf actor Jules Dameron radiates beneficence. Her friar becomes tenderly omniscient and omnipresent, partly because her voice pings from speaker to speaker — not only does her assigned shadow, Greta Boeringer, who doubles as the Duchess (erstwhile Prince Escalus) speak the friar’s lines, but so does Friar John (Darren Marquardt), an ad-hoc role that creates complicity in their deception — making it somewhat less condemnable.

Mosere also tinkered with time, but not in the way most directors do. She efficiently fuses two scenes into one so they occur simultaneously instead of consecutively. Actors freeze from frame to frame. Overall, a rack-focus effect of mini-tableaus is carried throughout the show, making audiences feel they’re getting at least two shows in one.

Performed outdoors in a grove of whispering pines and exotic hardwoods, the cast — about 20 versatile players — manages to populate an entire village of Verona through its own biodiversity: size, shape, age, ability, ethnicity. Mosere doesn’t flinch at injecting sight gags and pure goofiness. There’s as much comedy here as tragedy, especially with jesters like Jacob Urtes (Benvolio) in the mix. (How Shakespeare drama ever got labeled “high-brow” entertainment beats me — although Frederick, Maryland, Mayor Michael O’Connor attended the opening, much as dignitaries would receive command performances in the Bard’s day.)

The accessibility of this lively production may be just what Shakespeare intended.

That’s not to say elegance doesn’t reign. Robert Leembruggen as Lord Capulet conveys the classic Shakespearean vibe without coming off as Jon Lovitz’s master thespian. Portly and balding, with wispy silver curls, he looks the part in vintage velveteen vest, perhaps pulled from a trunk collection. With tremulous fingers and mellifluous tone, he caresses the literature; perhaps in a stuffier venue, each of his grand exits might have summoned applause. Meanwhile, Lady Capulet (Anika Harden) blends regal bearing with an earthy compassion so rare for the character. Her lyrical bedtime-story voice soothes even her harshest pronouncements.

While dwelling on voicing seems off-point for Deaf theater, vocal quality can make or break this hybrid form. The linchpin holding together what otherwise veers toward fractured storytelling is Mucciolo. Billed as Shadow Romeo, he’s no stand-in. With perfect poise and elocution, he’s the dream portal for hearing patrons, multitasking as narrator, troubadour, and Greek chorus (with a rock star quality).

Which brings us to the sonnet, the scene in which party-crashing, fickle-hearted Romeo first lays eyes on Juliet, then corners her and confesses his budding love.

I confess I couldn’t wait to see how the line “let lips do what hands do” would play out in a mixed Deaf-hearing production. What I didn’t expect: a song. Composer Garth Kravits has made Shakespeare’s poetic prose pop-chart worthy. OK, I’ll buy it. Who doesn’t binge on love songs when lovesick, especially as teenagers? Still, the effect proved not so transporting as it transported me into what felt like a Disney movie. (Original music by Kravits underscores the play throughout, performed by musicians Andrew Nixon and Nora Farahat, an incoming Hood College freshman, on cello and violins. On opening night, a pre-recorded version of the sonnet song, with vocals by Kravits and Lindsay Nicole Chambers, substituted for a live performance by Michael Mason and Allison Bradbury that others might be lucky to witness firsthand.)

Unfortunately, Surasree Das, while strikingly beautiful, does not strike the right note as Juliet. She approaches blue-blood loftiness: a tad shrill, scolding, sounding too mature for what should bespeak ardent adolescence. She stands as if on a pedestal in the balcony scene, atop a five-level platformed set, her nightgown kissed by the breeze, and we do finally see what Romeo sees. But for most of the evening, for me, it was ASL interpreter Alecia Cole who best embodied Juliet’s conjoined innocence and flowering womanhood. It was hard to take my eyes off her — then again, there is so much to absorb in this production it begs for a repeat viewing.

Some notes on costumes, designed by Tiffany Freeze. Juliet’s entire look is breathtaking. Her undergarment gown gets overlaid in salmon and meringue fabric, a silk bow in back, and glittering snood to hold in her braided hair.

Shear’s hotheaded red-haired Tybalt is also a standout dressed as what can best be described as a gothic polka-dotted buccaneer — with a large black belt symbolizing her fighting prowess and a cinched flame-color scarf draped as a half-kirtle, tying both her and Juliet into the “orange for Capulet” vs. “purple for Montague” theme. Shear, a pillar of the fight choreography team and resident intimacy coach, goes all in during her pivotal duel with the mocking Mercutio (Mani Yangilmau), whose long hair and uniquely colored sea-foam tunic set them apart from the other ruffians. Lighting design by Tabetha White enhances the battle — glints of red reflect in the sword blades. Moonlight, supplied by nature after sunset (along with ambient cricket sound), is enhanced with White’s purple haze.

Ensemble members echo Mercutio’s look in Viking shirts, tall laced boots, and coxcombs or porringer hats, sporting either orange or purple sashes to show which side they’re on. Refreshingly, though, Freeze also colors outside the lines. The delightful ragtag wardrobing reaches peak voltage with nurse Gillian Shelly’s pillowed pantaloon-like dress under a mustard shawl, our first clue that Shelly’s a consummate comic.

And the laughter? Epic. Laughter from both hearing and Deaf attendees erupts, interestingly at different times. The experience is both unifying and mysterious: What cryptic subtext is being conveyed in one channel and not the other? It’s an important reminder that we each bring our own perspective and capacity to theater, and that communication barriers can be bridged but never fully conquered. Obviously, a main goal of this production is to deepen our understanding of one another by improving communication — not just by hearing, but by internalizing the message, all senses firing.

To that end, cast members were taught ASL and rotate into signing or voicing other characters, including one wicked turn by phantom-player Stephen Kime, who speaks for Mercutio as they relate their nightmarish omen. Gives new meaning to “interpretive dance.” Nay, not a dance, this is an interpretation relay, as ESP actors hand off duties or maniacally race around the courtyard for scene changes. The action is quick-paced, underlining the rash decisions not only of star-crossed lovers but of those too quick to anger.

In a production nuanced and layered in duality, one of the most powerful scenes comes between Dameron’s friar and Castille’s Romeo: they milk pregnant pauses between lines, the silence deafening. Castille and Shelly, the nurse, also display great acting chemistry. It’s crystal-clear Shelly is “listening” and reacting directly to Romeo and not Shadow Romeo.

But the most masterful moment, hands down, is when Romeo discovers Juliet, lifeless, in her chamber. Castille’s writhing, wrenching performance needs no elaboration, yet violinists Nixon and Farahat exquisitely interpret his pain. Unspeakably moving, and so quiet you could hear a tear drop.

Running time: 2 hours and 15 minutes with a 15-minute intermission

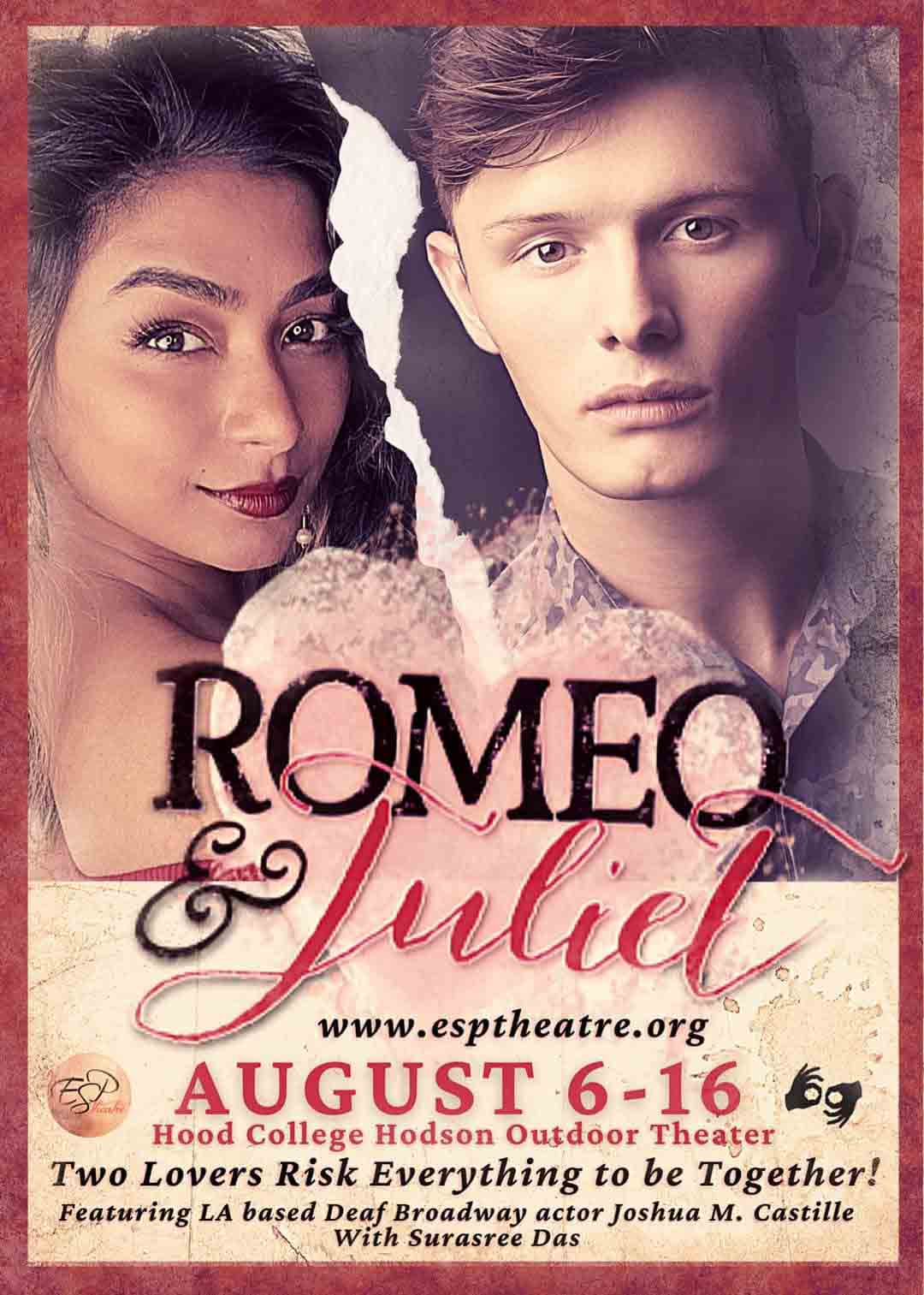

Romeo and Juliet plays August 6, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, and 16, 2021. Shows start at 7:30 p.m. except for on August 14 at 8:30 p.m. Performance venue is the Hodson Outdoor Theatre on the Hood College campus, 410 Rosemont Ave., Frederick, MD. Rain/weather location: Rosenstock Building. Tickets are pay-what-you-can and available at esptheatre.org. Each performance will have ASL interpreters. Call 301-305-1405 or email [email protected] for more information.

Romeo and Juliet — directed by Christine Mosere with assistant direction by Deaf artist Neil Sprouse — stars Deaf actor Joshua M. Castille as Romeo and Surasree Das as Juliet with other cast members including Deaf actor Jules Dameron as Friar Lawrence, and Greta Boeringer, Jeffrey Fleming, Kailey Azure Green, Anika Harden, Marina Jansen, Stephen Kime, Charlotte Leembruggen, Mallory Leembruggen, Robert Leembruggen, Sarah Leembruggen, Robert Lewandowski, Darren Marquardt, Joe Mucciolo, Mallory Shear, Gillian Shelly, Daniel Summerstay, Jacob Urtes, and Mani Yangilmau.

SEE ALSO: On directing R&J with a Deaf Romeo: A Q&A with Christine Mosere interview by Terry Byrne

______

A note to readers: This review has been revised to remove three isolated descriptions that careful readers called to our attention as offensive. The author, herself a woman of color, deeply regrets inadvertently choosing words that could be perceived as targeting anyone’s ethnicity, hairstyle, or gender. DC Theater Arts and all its staff members are committed to a spirit of inclusivity, celebrating the diversity and beauty of all artists.

I don’t appreciate the way you portrayed the women of color in this article. Using the terms “Charcoal mane” and “horse tail hair” is incredibly racist. I would’ve expected a woman of your age to know these things. I don’t know how you can call yourself an objective critic when you painfully inserted your preconceived notions of how women are supposed to act, especially when you weren’t even paying attention to the person you were criticizing. Shame on you.

Comparing a POC actor’s performance to Aladdin and Jasmine is a bad look. They didn’t work this hard for that kind of disrespect.

What about your response to “revision” gives reassurance to Surasree or any Black, Brown, Indigenous or POC actors?

Will the author/critic Terry Byrne and DCMTA be directly and PUBLICLY apologizing to Surasree? What will you do to take accountability for this and what you plan to do to make sure this won’t happen again? It’s very easy to post a “we didn’t mean it” / “it wasn’t our intention”-type response and hide away from the person who has truly been harmed by this racism.

I’m deeply concerned about: “Descriptions some readers found offensive?” Does that mean DCMTA *did not* find those descriptions racist? Why the need to include that Terry Byrne is a “woman of color” in your response? What was the reason behind mentioning that?

The response to the “revision” has a lot more defense for DCMTA and Terry Byrne than compassion and accountability toward Surasree.