When I finished James Lapine’s new book about the making of the musical Sunday in the Park with George, my first reaction was to channel another Sondheim/Lapine collaboration, Into the Woods:

What was that?!

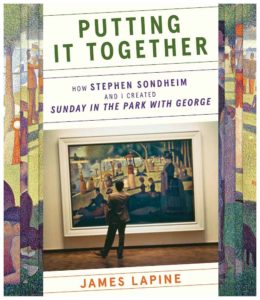

The title of Lapine’s book — Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created “Sunday in the Park With George” — promised a memoir by the book writer and director of the 1984 Broadway musical about George Seurat. Or at least a traditional narrative.

So I was stunned that after a few introductory pages that take us from the Mansfield, Ohio, native’s first trip to Broadway at age 11 (to see Dick Van Dyke in Bye Bye Birdie) to his early directorial experiments in New Haven and New York, the author vanishes.

One of those early experiments, Photograph, a theme-and-variations play based on photographic images, formed the protomatter of a musical that he and composer/lyricist Steven Sondheim would labor over a two-year period from 1982 to 1984 to create: The story of French pointillist painter Georges Seurat’s own struggle, 100 years earlier, to create his masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

We are just beginning to hear Lapine’s version of that story when the book transforms into something resembling a deposition in a civil lawsuit. I initially felt confused by this, even a little cheated.

Why am I reading 200 pages of transcribed interviews about a musical that received a Tony nomination for Best Musical, and won the 1985 Pulitzer Prize for Drama? Was the process of making this musical so traumatic or tortious as to warrant a legal investigation?

To answer that question, Lapine presents transcribed interviews with some 40 players involved in the making of Sunday in the Park with George, from original cast members (including Mandy Patinkin and Bernadette Peters, who played George Seurat and his aptly named mistress, Dot) to producers to musicians to costumers and even the graphic designer who made the poster.

You can’t quite call this approach journalism. In journalism, you marshal your interviews into a story. As Patinkin’s George Seurat might say, you have to bring order to the whole.

Lapine describes his book as a “mixed salad” consisting of memoir, oral history, and a primer on how to make a musical. He defends this unusual structure by pointing to the unreliable nature of memory and by arguing that, in memoir writing, “emotional recall often wins the day over fact.”

He may be right about both points, but does any of us really read memoir for the literal, objective truth? Isn’t emotional recall — how the author felt about the events he’s describing — always more interesting than a mere recitation of facts?

Perhaps Lapine didn’t trust himself to write a memoir about a show for which he feels such ambivalence.

“Working with Sondheim was a dream come true,” he writes. “On the other hand, my memories of directing the production remain complicated and occasionally painful. At least, that’s the feeling I have carried with me all these years.”

I agree that viewing this book as an oral history is essential to understanding what it’s attempting to do. Judged by that standard, it’s a grand succès.

Putting It Together is not, however, a passive pleasure. Wading through these transcripts and keeping track of dozens of interviewees, with only intermittent patches of narration and sparse, Kubrickian chapter titles to orient you (“1983”), isn’t easy. Then again, as Sondheim tells us, neither is art.

The story of how Sunday in the Park With George came to be is fascinating.

In 1982, Lapine was a hot new item in New York theater, having made his debut by directing an avant-garde production about Gertrude Stein in a SoHo loft, funded by Jasper Johns (moral: you never know until you ask, so ask). Sondheim, already a legend in musical theater, was in a rut after the critical shellacking he had received over Merrily We Roll Along.

Sondheim invited the younger Lapine to his Turtle Bay townhouse, perhaps hoping to be reinvigorated with a little of Lapine’s downtown energy. Despite their generational and geographical divide, the two men instantly bonded over their shared interest in Buñuel films and blunts. They shared a joint, tossed photographs on Sondheim’s Persian carpets, and somehow came up with the idea to make a musical about Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

Lapine immediately started writing the book, unsure of where he was heading, only knowing that the first act would end with a recreation of the painting.

The two men made a pilgrimage to the Art Institute of Chicago for an up-close-and-personal look at the painting, where museum staff showed them X-ray photographs that had been taken of the canvas, revealing the many revisions Seurat made to his masterpiece during the two years it took him to complete it. “We were really able to get a sense of Seurat’s obsessional nature: the exactitude of his work and the precision of every brushstroke on the canvas,” Lapine writes.

Remind you of anyone?

The musical, directed by Lapine, with music and lyrics by Sondheim, opened off-Broadway in 1983, with Patinkin as George, Peters as Dot, and a young Kelsey Grammer, pre-Cheers, as Young Man/Soldier. At the first preview, audience members fled.

I’ll let Lapine and Sondheim describe the scene:

LAPINE: It was not a good start.

SONDHEIM: It was terrible. I remember the look on your face. You had never been walked out on before. You had never experienced that because you had been writing for off-Broadway, where nobody ever walks out because the weirder or more boring the show is, the happier they are to be there. I wanted to say, or maybe I did, “It happens to me all the time, James. Get used to it.”

LAPINE: The actors could feel the resistance of the audience. They were also pouring sweat onstage. I really thought I was going to have a heart attack that night, and I was kind of hoping I would so I wouldn’t have to come in the next day.

SONDHEIM: Welcome to commercial theater . . .

The best parts of Putting it Together read like this, funny and brutally honest. Occasionally, these recollections transport you. There is one scene, in which Patinkin describes meeting Sondheim for the first time, that is so perfectly composed, it almost approaches art.

PATINKIN: In ’78, while I was doing Evita, I was at a party at Hal Prince’s house, and there was a back room that had a baby grand piano. I didn’t want to hang out with the crowd, so I went into the room and sat on the couch next to a lady. I didn’t know who the lady was at first, and we started talking. It turned out it was Angela Lansbury, and it was an extraordinary conversation. And, as I’m talking to her, I realize it’s the wrong guy sitting there—it should have been my late father. How he loved this woman. The first time I visited New York — my bar mitzvah gift — my dad took me to see her in Mame. And as I’m having this thought about my dad, a guy walks in the room and Angela stands up and says, “Mandy, I’d like you to meet Stephen Sondheim.” And at that moment, I did not have it together in my head that he was the guy who wrote West Side Story, but a click went off, because my roommate Ted Chapin had shown me this album he had of a Sondheim benefit concert where Sondheim’s name was spelled out with Scrabble tiles. “Well, you’re the guy on the Scrabble album, aren’t you?” and Steve said, “Yeah.” I said, “You performed that amazing song ‘Anyone Can Whistle’ on that recording, right?” and he said, “Yeah.” And then I asked, “Could you play that for us now?” So he sat down at the piano for just Angela and me, and sang “Anyone Can Whistle.” That’s the first time I met Stephen Sondheim.

The book wisely avoids paeans to Sondheim’s brilliance, but if it has a fault, it’s that it contains too many professions of insecurity. Peters is afraid to play an old woman. Lapine intimidates Patinkin. Lapine is afraid to work with Patinkin. Everyone is afraid to audition for Sondheim. The insecure actor has become a cliché at this point.

What’s more interesting, and worth the price of admission here, are the scenes in which actors reflect on their struggles with the material, a piece of art about a piece of art.

In one standout scene, Brent Spiner, of Star Trek: The Next Generation fame, who played Franz in the Off-Broadway and Broadway productions, remembers confronting director Lapine, saying, “I don’t have a character. Where is my character?” Lapine said, “You’re not a character, you’re a color.” And Spiner replied, “Oh, well, would you mind telling me what color?”

At its best, Putting It Together is not just a book about the making of Sunday in the Park with George. It is also a book about the art of making art. And that journey, we learn, can be chaotic.

But from that chaos, Lapine manages to assemble a tableau vivant. After 200+ pages of interviews full of kvetching and catharsis, Lapine ends with the full script of Sunday in the Park With George, and the book, just as the show and painting that inspired it, snaps firmly and forever in place.

Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created “Sunday in the Park with George” by James Lapine is published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and on sale now.

SEE ALSO:

Putting It Together – ‘Something Wonderful: Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Broadway Revolution,’ by Todd S. Purdom book review by Geoffrey Melada

The Baron of Broadway, ‘Unmasked: A Memoir’ by Andrew Lloyd Webber book review by Geoffrey Melada