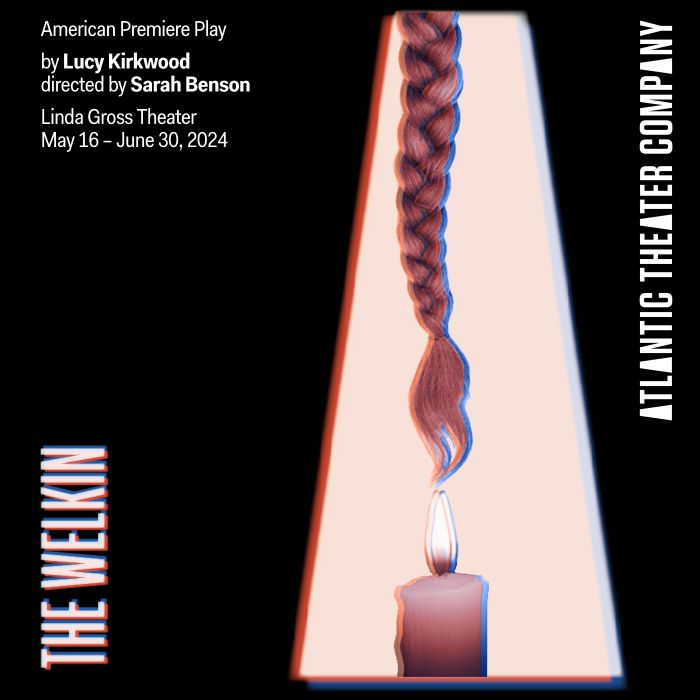

Though set in rural England in 1759, The Welkin, a new dark comedy written by Lucy Kirkwood and now making its Off-Broadway debut at Atlantic Theater Company, is filled with heavy-handed anachronisms, an array of inconsistent accents and speech patterns, over-the-top plot points and character revelations, and segments of surreal absurdism that unduly belabor the point that women are still universally stereotyped, treated with inequality, and only valued for doing housework and giving birth (and appearing nude on stage). Or can it just be blamed on the effect of Halley’s Comet (the old English word “welkin” means the firmament) and recurrent cycles in history?

Directed by Sarah Benson with ferocity and a high decibel level, Haley Wong appears naked, bloody, mean, loud, foul-mouthed, and unabashedly post-modern as Sally Poppy, convicted of brutally murdering a little girl from a wealthy family in the community, for which she is to be hanged. But her claim of being pregnant necessitates a jury of twelve local women to determine unanimously if she’s lying and to decide her fate. They are led by Sandra Oh (who was having trouble remembering her extensive lines at the press performance I attended) as the intelligent and more compassionate proto-feminist midwife Lizzy Luke, who believes and defends her, and has a big secret from her past that ultimately comes to light and explains her determination to try her best to save the antagonistic Sally, whose lover was already executed for their joint crime.

Others of the twelve angry women on the jury, of different ages, classes, opinions, and fecundity (Tilly Botsford as Kitty Givens, Hannah Cabell as Sarah Hollis, Paige Gilbert as Hannah Rusted, Ann Harada as Judith Brewer, Jennifer Nikki Kidwell as Ann Lavender, Nadine Malouf as Emma Jenkins, Mary McCann as Charlotte Cary, Emily Cass McDonnell as Helen Ludlow, Susannah Perkins as Mary Middleton, Simone Recasner as Peg Carter, and Dale Soules as Sarah Smith), initially seen doing household chores, then introduced individually by giving statements about their mundane lives as they are sworn in and “kiss the book,” also have their own highly contrived backstories and hidden agendas that are exposed in the drawn-out second act (each of which seems to be the conclusion but still isn’t). And after disagreeing, insulting, and battling with each other throughout the deliberations, the unlikeable characters join together for a group rendition of the female pop band The Bangles’ 1986 hit “Manic Monday” (the year in which Halley’s Comet last reappeared and a title that refers to the traditional belittling of women as being prone to hysteria – though the song was written and originally intended to be sung by the male artist Prince).

In addition to the women are the men in charge of the patriarchal society: Glenn Fitzgerald as Mr. Coombs, the bailiff overseeing the prisoner and the jury of women; Danny Wolohan as Sally’s controlling, abusive, and cuckolded husband Frederick Poppy, who turns her in, and as The Doctor, who’s called in to examine her (the extremely heavy metal instrument he invented for ob-gyn exams is one of the most effective sight gags in the show; props by Noah Mease) and to diagnose the pregnancy, even though Lizzy, the longtime midwife, has already given her professional determination; and Sally’s unseen hanged lover, for whom she’d do anything (including being an accomplice to murder). Along with the adults, MacKenzie Mercer appears as the young Katy Luke, representing the next generation of women churning butter, and there are strange apparitions of eerie figures that add an otherworldly element to the melodramatic comedy, in a messy mash-up of unsympathetic characters and overblown theatrical devices that detract from the underlying themes of the subjugation of women throughout history and men’s greater knowledge and interest in the workings of the universe than about women’s bodies and minds.

An historicizing set by dots, with wooden furnishings, a large stone fireplace, and a leaded glass window that opens to the jeers of a bloodthirsty mob outside the jury room, is enhanced with a creepy soundscape by Palmer Hefferan, dark lighting by Stacey Derosier (often so dark that’s it’s difficult to see what’s going on in the scenes), with bright illumination from the passing comet and spotlights on the women speaking, and special effects by Jeremy Chernick, which include a fiery explosion that saturates some of the drawn evidence of Sally’s pregnancy with soot. An anachronistic mix of then and now, costumes by Kaye Voyce, hair and wigs by Cookie Jordan, and make-up by Gabrielle Vincent help identify the general circumstances of the characters, with movement by David Neumann, fight direction by Sean Griffin and Gerardo Rodriguez, and intimacy direction by Crista Marie Jackson that define their interactions and show them at odds.

What The Welkin lacks in subtlety it over-compensates for in length. Everyone has a different sense of humor and taste in comedy, but for me, this was overloaded, unfocused, and in need of some serious editing. And if you’re looking for a laugh-out-loud happy ending, you should go see a musical.

Running Time: Approximately two hours and 30 minutes, including an intermission.

The Welkin plays through Sunday, July 7, 2024, at Atlantic Theater Company, performing at the Linda Gross Theater, 336 West 20th Street, NYC. For tickets (priced at $56.50-121.50, including fees), call (646) 452-2220, or go online.