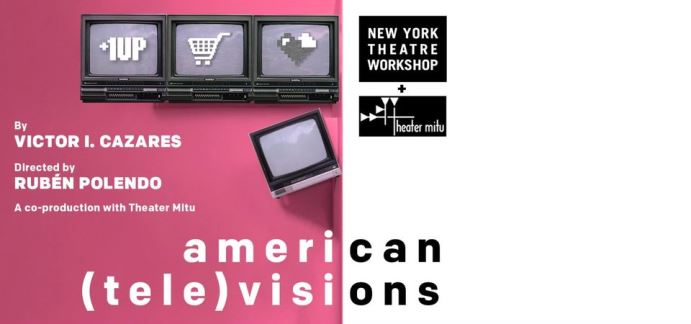

In the nonlinear multimedia memory play american (tele)visions, now playing a limited engagement at New York Theatre Workshop, Tow Playwright-in-Residence Victor I. Cazares relays how it might have felt for one child to be an undocumented Mexican immigrant growing up in America in the 1990s. Directed by Rubén Polendo, the challenging experimental work, which has been in development since 2007, is a co-presentation of NYTW and Theater Mitu, where Polendo serves as Founding Artistic Director.

Overwhelmed in youth by familial conflict, sexual identity, low income, and consumerism, and bombarded with the TV and video tech of the era, Erica navigates through a fever dream of recollections, revelations, and emotions, as the hope for living the “American Dream” too often becomes a nightmare. Inspired and informed by four dozen textual and artistic sources (the list of referenced materials is included with the printed program), Cazeles combines direct-address narration, poetic passages, and live performance re-enactments with pre-recorded videos, live camera feeds, and voice-overs, in styles that encompass everything from absurdism, surrealism, and abstraction to comedy, fantasy, melodrama, and realism. The stylistic disparities and multisensory overload can be distracting and the achronological segments are sometimes redundant; even if intended to be indicative of the character’s flooding thoughts, the show could use some tightening and focus.

Central to the story are the family outings to Walmart, where they disperse to their favorite aisles (Erica’s is the toy section, with gay and disabled friend Jeremy, who prefers Barbie dolls to the traditional boy toys Erica loves), meet around their filled shopping cart, and argue over what they can afford to buy (one of the most affecting lines is the realization that “dollars are only better than pesos if you have them”). Other scenes take place in the family’s cramped living room, where the father Octavio spends most of his off time on the sofa watching television, and in front of the truck driven by Stanley, the unseen lover of his wife Maria Ximena – both locales set inside the double-stacked cargo containers that flank the stage and are opened manually by the cast (set design by Bretta Gerecke).

Additional key episodes, including imagined video games that reflect their lives and a secret sex tape of Alejandro and Jesse – the couple’s gay son and the Asian boy they took in – are projected on the storage blocks, the backdrop, and the high side walls of the stage that surround the actors and dominate the space (technology design by Theater Mitu: Kelly Colburn, Alex Hawthorn, and Justin Nestor), much as they dominated American culture in the ‘90s. The cast of five shifts from one disparate style and format to another, giving glimpses into their characters’ personalities and stories through the memories that permeate Erica’s mind, with discordant sound, sudden blackouts, and flashes of light between (lighting by Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew).

Bianca “b” Norwood stars as Erica, the young tomboy reflecting on the experiences of America, capitalism, dysfunction, infidelity, death, sexuality, and relationships, who at times screams, at times laughs, when dealing with life’s struggles and the escapism of video games, which here provide no real escape, just transference and amplification of the issues. Raúl Castillo as Octavio is angry about his low-paying job, his cheating wife, and gay son and friend, to the point of his outrage and homophobia turning physical (fight direction by David Brimmer). Elia Monte-Brown displays the frustration, grief, desire, materialism, and trauma of Maria Ximena, bearing “2500 tons of sorrow” for leaving her country (though her appearance as the personification of Walmartina, in a tight-fitting black-and-white gown printed with bar codes, is one of the show’s most over-the-top funny scenes).

The charming Clew does double duty in the parts of both Jesse and Alejandro (after being asked by Maria Ximena to assume the role of her son in the re-enacted nostalgic recollections), who we soon discover, is no longer alive (nor is another member of the divided family, as also comes to light). And Ryan J. Haddad’s Jeremy adds touches of flamboyant humor in his identification with Barbie and his donning of a princess dress and crown (costumes by Gerecke, with Mondo Guerra providing the specialty costumes).

In general, the motivation for american (tele)visions is important and meaningful, especially in these current times of embattled immigration rights and the call for increased inclusivity. But I found its presentation to be too overloaded, repetitive, and gimmicky, scattered and disjointed, to deliver a fully satisfying and coherent experience and message.

Running Time: Approximately 95 minutes, without intermission.

american (tele)visions plays through Sunday, October 16, 2022, at New York Theatre Workshop, 79 East 4th Street, NYC. For tickets (priced at $25-65, plus a $4.00 service fee), go online. Everyone is required to wear a mask while inside the building.