When Lorraine Hansberry’s classic A Raisin in the Sun opened on Broadway in 1959, I was a child in an all-white suburb on the north side of Buffalo, New York, a city with a significant Black population. To the best of my knowledge, there were no Black families in this town of around 100,000 people. I had no non-white classmates in my schools. I hadn’t yet learned about racially restrictive covenants and redlining, but even then the situation felt strange and ominous.

I don’t know whether a family like Hansberry’s Youngers ever tried to buy a house in my town. If they had, a combination of legal, financial, and community obstacles would likely have stood in their way. Having personally grown up on the other side of racial line-drawing that affects the Youngers in the play, so pervasive in American life at that time, and persisting through today in a variety of forms, I’m struck with the continuing vitality of what Hansberry has to say.

While finding that new home is a central plot point in Hansberry’s story (reflecting her own family’s experience with restrictive covenants in the 1940s), A Raisin in the Sun, as shown in Sterling Playmakers’ moving production, is far more than simply a play about housing discrimination.

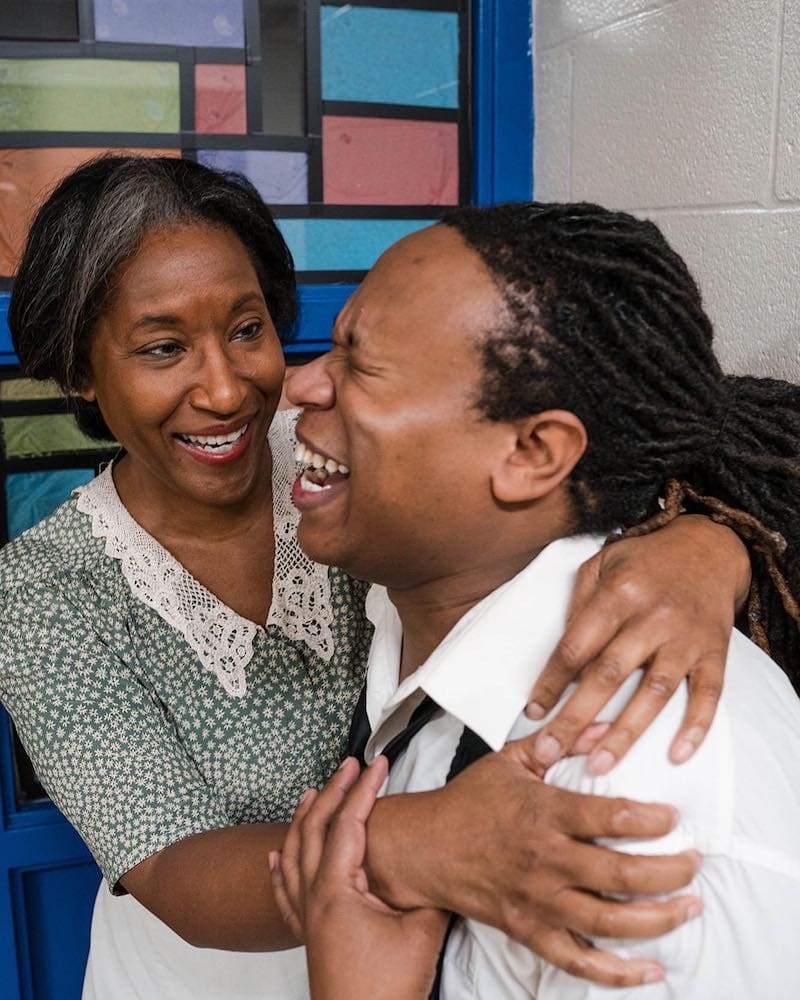

At the center of the family, and of this production, is Lena Younger, the matriarch of the family. In a powerful, varied, nuanced performance, Robin Lynn Reaves gives us Lena’s realism, hope, traditionalism, and endurance, bred of five generations of her family through slavery, Jim Crow, and the Great Migration. The insurance payment she receives following her husband’s death offers a way out of the family’s financial problems while triggering conflict among its members. The one moment when Reaves’ Lena cries out in anger and despair is harrowing.

Lena’s two children markedly differ from each other. Tyrus Sanders portrays her son, the mercurial, immature Walter Lee Younger. Sanders’ Walter Lee can be weak, drunk, angry, wounded, and demanding, insisting on using his mother’s inheritance to fund his dream of opening a liquor store. As he imagines the store’s success, he brims with happiness as he tells his young son Travis (Caleb Dawkins) how wonderful and rich their new life will be. He is also both deceitful and gullible when it comes to the family’s money. It is not until the very end of the play, when things are most dire, that he acts as a responsible man. Sanders handles the character’s mood changes effectively, though at times he could better modulate the speed and volume of his line delivery.

Walter Lee’s sister, Beneatha (Angela Whittaker), a college student with aspirations of becoming a doctor, is all enthusiasm and energy, frequently expressed through broad gestures, quick movement around the stage, and ebullient poses. She cares not only about her own future but also about learning and the circumstances of Black people here and in Africa. Beneatha embodies some of Hansberry’s vision of what it means to be young, gifted, and Black. As a kind of preface to Act 3 of the play, Whittaker sings a strikingly beautiful rendition of “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.”

Beneatha’s interest in Africa is sparked by a Nigerian man she is dating, Joseph Asagai (Evan Carrington). He is wholeheartedly and idealistically committed to the anti-colonialist cause in mid-20th-century Africa. Beneatha insightfully asks him whether British and French oppression might simply be replaced by home-grown oppression, but that is something that, given the uncertainty of the future, he says he will confront later. He gives her a beautiful Nigerian robe, so she can have a sense of what his culture feels like. He talks of marrying her and their moving to his country.

The other man interested in Beneatha, George Murchison (Curtis Lewis), is an affluent “assimilationist,” someone who seeks success by meeting the expectations of white society. A humorless stuffed shirt, he has no chance with Beneatha.

Walter Lee’s much put-upon wife, Ruth (Marguerite Driessen), is often tired, not only from having to deal with the family’s strained financial circumstances but from her husband’s mood changes. Troubled by an unexpected pregnancy, her hopes are buoyed by the prospect of being able to move from a roach-infested apartment to a real house.

The villain of the piece, of course, is the entire system of white supremacy and its corrosive effects on Black lives. Its representative in the play is the most awkward and nerdy of racists, Karl Linder (John Geddie), an official of the civic association of the neighborhood into which the Youngers want to move. “You people,” as he calls the Youngers, just wouldn’t be welcome, he explains, so he offers to buy them out at a premium. The Youngers, finding him ridiculous, initially throw him out, but then reconsider when their financial circumstances take a disastrous turn.

By the way, Linder’s sentiments are not merely relics of the past. Just last week, Scott Adams, creator of the popular Dilbert comic strip, said on a livestream quoted in the HuffPost and other media sources, “The best advice I would give to white people is to get the hell away from Black people…You just have to escape. So that’s what I did, I went to a neighborhood where I have a very low Black population.” Several publications dropped the strip as a result.

Two cameo roles merit mention. Eleanor Tapscott appears as a particularly annoying neighbor, Mrs. Johnson, while D’Andre Stewart plays Walter Lee’s friend Bobo, who brings bad news to the family. Both provide well-defined characterizations in their brief moments on stage.

The realistic set design (Scott Ruegg and Terry DiMurro) spreads across the broad Seneca Ridge Middle School stage. With neat blue wallpaper and serviceable furniture, it looks less decrepit than the script’s description of the Youngers’ apartment. Probably the result of limited resources in the facility, Marie Casey’s lighting is mostly either switched on or switched off, with occasional dimming and the use of a special for Beneatha’s third act monologue. With African-themed outfits and a couple pretty dresses, Beneatha wears the highlights of costume manager Shirlyn Baker’s efforts, though the sheer weirdness of Linder’s costume, argyle sweater and all, made the appropriate impression for the character.

In contrast to the current trend of 90-minute, small cast one-acts, Hansberry’s longer, three-act structure and the play’s often brilliant words allow leisurely development of characters — full portraits, not just sketches — giving the actors and the director Lauren Baker the opportunity to create the complete world of the Younger family. They do not miss the opportunity. This is a cohesive production that combines Hansberry’s commentary and the human feelings of its characters in a way that cannot but affect the minds and hearts of those who view it.

Running Time: Two hours 45 minutes, including one intermission.

A Raisin in the Sun plays through March 5, 2023, presented by the Sterling Playmakers performing at Sterling Ridge Middle School, 98 Sterling Ridge Road, Sterling VA. Tickets ($18) are available online and at the door.

The cast list is online here.

COVID Safety: Masks are recommended but not required. Sterling Playmakers’ Pandemic Policies and Procedures may be found here.