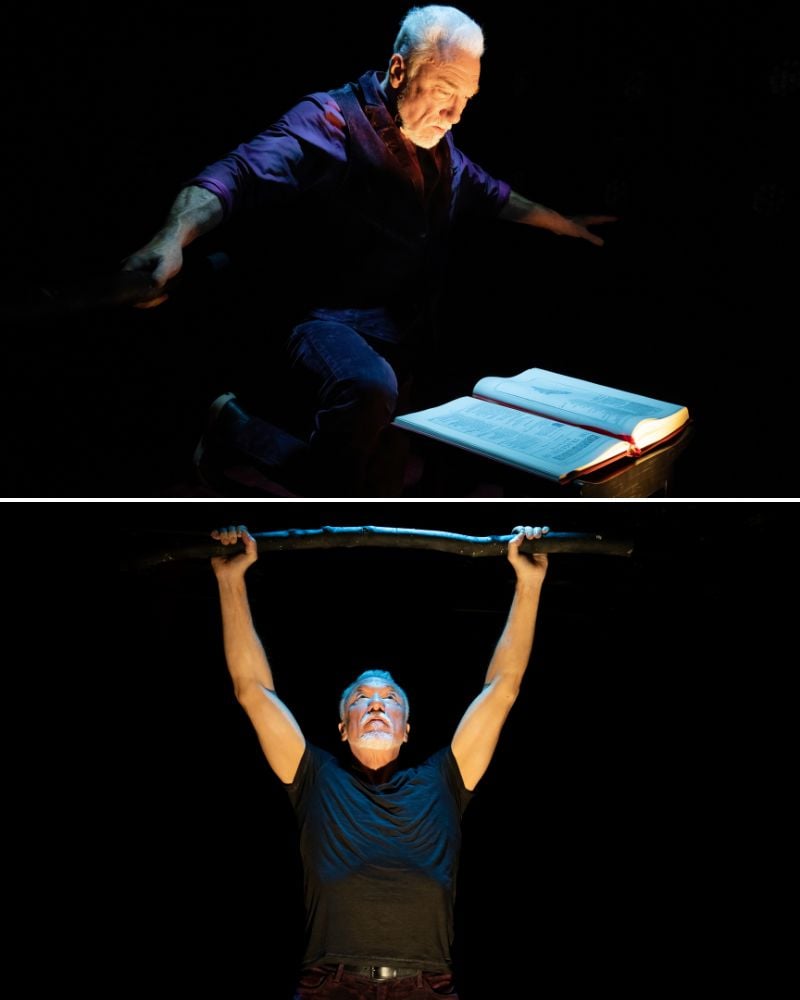

Anyone who saw Patrick Page in the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s magnificent 2023 production of King Lear would expect nothing less than a spectacular performance by Page in his one-man show about Shakespeare’s villains, All the Devils are Here. Page delivers.

Directed by Simon Godwin, Page displays all the astonishing tools at his command: vocal power and variety, endlessly variable physicality, and exquisite timing, including the ability to transfix the audience with a pause. No movement or inflection is wasted in a taut 90-minute chronological tour of the evildoers Shakespeare created between 1590 and 1611.

The production is aided by strong sound and light designs created by Darron L. West and Stacey Derosier, respectively. Precisely aimed and timed, and with due attention to the emotional effects of color, the lighting not only keeps focus on what matters most at a given moment but sets the mood in each sequence of the play. Red is often the predominant color, but during the Iago scene, for example, green lights come to the fore as the “green-eyed monster” takes charge. The sound design at times is puckish — “Bad Bad Leroy Brown” is a major part of the pre-show and curtain call music — but generally serves to underline the ominous tone of the material or highlight dramatic changes, for example as Macbeth goes about his homicidal business.

Page created the show, and he uses its scenes as an occasion for educating as well as entertaining his audience, in a way that reminded me, in a very different style and medium, of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts. His thesis is that as Shakespeare’s art evolved over 21 years, the psychology of his villains became more layered and complex.

To illustrate this viewpoint, Page selects often brief scenes highlighting the psyches of his characters. There’s Richard III’s bitter hatred of his treatment as someone with a disability, Shylock’s cruel response to the antisemitic cruelty shown him, the ambition of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, etc. Some of the scenes are monologues, but several times Page plays a pair of characters: Antonio and Shylock, Iago and Othello, Macbeth and his Lady. With subtle changes in body position, voice, or use of a small prop, Page switches seamlessly and impressively between characters in the conversation.

Not all the villains get equal time. We get only a glance of Edmund from King Lear, while the regicides of Macbeth have an extended time to strut and fret upon the stage, backed by the evening’s most striking technical effects. Some of the vignettes are particularly touching: Shylock expressing the pain of antisemitism and Claudius experiencing the futility of prayer to express remorse while he continues to benefit from the fruits of his crime were particularly poignant.

In discussing Iago, Page makes the interesting point that this villain checks all the boxes for being a sociopath (in the process making an analogy to a certain unnamed current leader, eliciting a rueful laugh from the audience). I wonder. Diagnosing Iago as a sociopath may well be an accurate description, but does it have explanatory power, like ambition for Macbeth? Need there be a diagnosis or explanation at all? There’s an argument to be made that the impact of Iago as a villain comes precisely from the fact that his evil is not capable of explanation, it just is.

Page bookends the show with references to The Tempest, ending with Prospero letting go not only of his captives but of his long-harbored desire for revenge. How better to conclude an exploration of the terrible things people do in service of their darker drives than with the choice of a major character not to be a villain but to accept that, in Prospero’s famous line, “We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.”

Lovers of Shakespeare will enjoy Page’s survey of some of Shakespeare’s most fascinating characters, along with his intellectual work in understanding how they fit into the Bard’s development as a playwright. Even those without extensive familiarity with Shakespeare will appreciate the crystal clarity of Page’s characterizations. And anyone with a theatrical bone in their body will be thrilled by experiencing this genuinely great actor at the height of his powers.

Running Time: 90 minutes, with no intermission.

All the Devils Are Here: How Shakespeare Invented the Villain plays through December 29, 2024, at Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Michael R. Klein Theatre (formerly the Lansburgh) – 450 7th Street NW, Washington, DC. Tickets ($59–$131) are available at the box office, online, or by calling (202) 547-1122. STC offers discounts for military servicepeople, first responders, senior citizens, young people, and neighbors, as well as rush tickets. Contact the Box Office or visit Shakespearetheatre.org/tickets-and-events/special-offers/ for more information. Audio-described and ASL-interpreted performances are also available.

The Asides program for All the Devils Are Here is online here.

COVID Safety: All STC spaces are mask-friendly — meaning all patrons, masks and unmasked, are welcome. Read more about Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Health and Safety policies here.

All the Devils Are Here: How Shakespeare Invented the Villain

Created and performed by Patrick Page

Directed by Simon Godwin

An Octopus Theatricals Production

SEE ALSO:

O villainy! Patrick Page slays in ‘All the Devils Are Here’ from STC (review of the original online-only production by Sophia Howes, February 3, 2024)

Understanding and embodying Shakespeare’s villains in ‘All the Devils Are Here’ at Off-Broadway’s DR2 Theatre (review of the production Off-Broadway by Deb Miller, October 16, 2023)