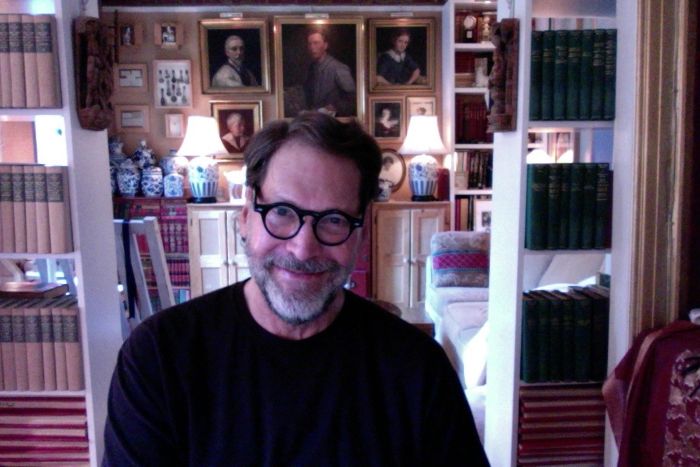

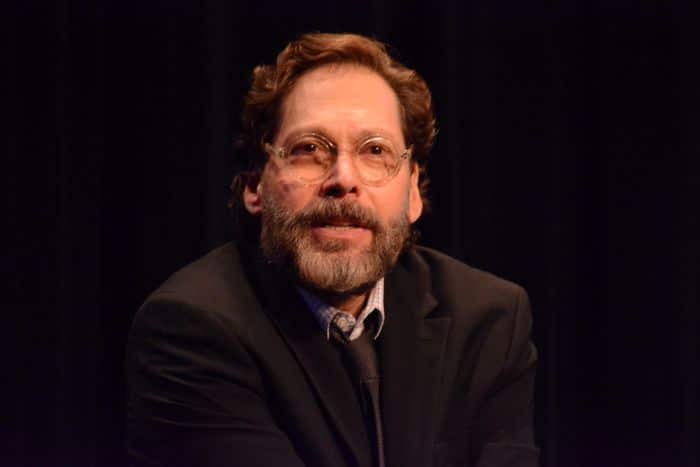

As the Founding Artistic Director of NYC’s Gingold Theatrical Group, named for British actress Hermione Gingold (his godmother) and created in 2006 to champion human rights and free speech using the work and humanitarian precepts of Irish playwright (George) Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), David Staller is the first person to have directed all 65 of Shaw’s plays, including his last unfinished work, Why She Would Not, for GTG, with the company’s full Off-Broadway productions of eleven of Shaw’s plays filmed by The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. Staller also oversees the monthly series Project Shaw, now in its 20th year, at Symphony Space and New York’s legendary club The Players.

Creating Gingold Theatrical Group was not designed as a career move for Staller; as he put it, although he had never heard of himself, he was never out of work as an actor, director, or writer. He was, in fact, starring in a New York production of Shaw’s Mrs. Warren’s Profession opposite Dana Ivey when he and some friends decided to create an activist theatrical organization to “promote peaceful discussion and activism” with the work of GBS as their guide. He has also created academic partnerships with several NY schools, including the Barnard, Columbia, Marymount, The New School, Regis High School, the Broome Street Academy, and SUNY Stony Brook, in addition to GTG’s new play development program Speakers’ Corner, and has personally spent years researching all of Shaw’s published versions of plays and has adapted all of Shaw’s works, often using the playwright’s original hand-written manuscripts, letters, production scripts, notes, and in-person interviews with many of those who knew and worked with him, including Maurice Evans, Robert Morely, Wendy Hiller, Rex Harrison, and Deborah Kerr.

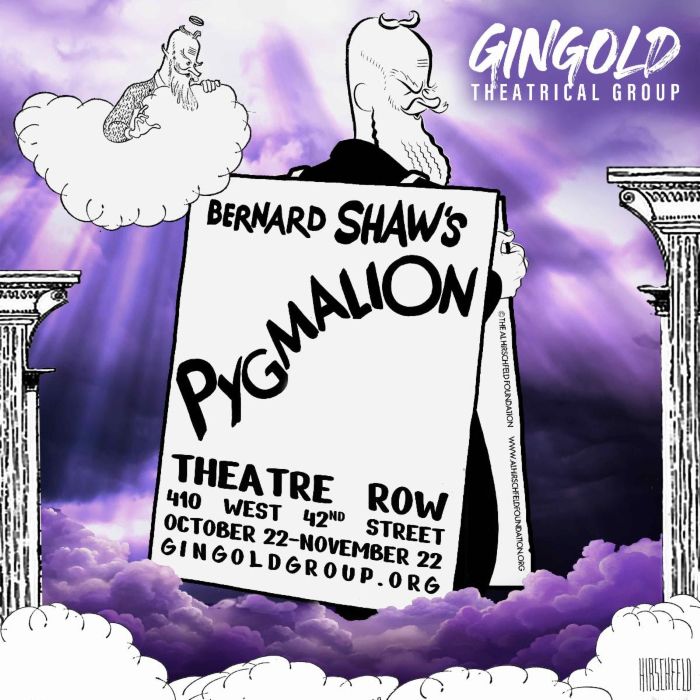

GTG’s latest production, directed by Staller, is Shaw’s most famous play of 1914, Pygmalion, a rollicking comedy set in pre-WWI London that lampoons the rigid British class system of the day with themes of identity, power, transformation, and women’s independence, which inspired Shaw’s 1938 Oscar-winning film adaptation and the 1956 Tony-winning musical My Fair Lady. During a busy week of rehearsals, David made time to answer my questions about the playwright, the show, and his production’s unique design.

How did you come to specialize in the work of Shaw?

David: Exploring the landscape of George Bernard Shaw’s contributions to society has unexpectedly become a sort of life’s work for me. My introduction to Shaw came from my godmother, the acclaimed if eccentric British actress Hermione Gingold, who had revered and even known Shaw. By the time I was ten, we were engaging in a robust correspondence in which she patiently responded to the usual questions children might ask until she finally wrote, “Darling, I love you but you have got to start asking more compelling questions.” This letter was accompanied by a copy of Shaw’s monumental Man and Superman. “Just read it,” she wrote, “Take your time and let me know where it takes you.” I still recall the joy of discovering how accessible and funny the play was, and how it triggered an endless number of new ideas. It was the beginning of my understanding of Shaw’s bold humanitarian precepts, the notion that challenging everything was not only acceptable but was a step toward forging our own unique opinions and points of view. I continued these Shavian exploration by reading all of Shaw’s works, which helped to broaden and deepen my exposure to Shaw’s core principles and ideas.

Central to my basic interest was by learning of Shaw’s early struggles in Dublin, as a troubled and lonely child who never finished school, and that Shaw determined never to allow anyone to diminish him. Shaw’s journey inspired me to face my teen years with an empowering confidence I might otherwise have lacked. By the 1970s, while still a questing teenager, Hermione and I were both living in New York City. Her Manhattan sitting room became a Sunday salon of actors and playwrights who gathered to discuss their fascination with Shaw’s plays and, even more compellingly, Shaw’s overt socio-political activism. Many had actually known and loved the man, sharing Shaw’s deeply rooted commitment to social welfare. At these Sunday afternoon gatherings, the group would allow me to choose a play, from which they’d claim roles to read aloud, and always featured in-depth discussions of the characters and their journey, even stopping in the midst of the readings with animated comments, questions, and observations. Though these little parties generally began at teatime, they’d often careen into cocktail hour with unexpected and robust approaches to performing the plays.

The first play I chose, to general delight, was Pygmalion. Hermione’s agent, the legendary Milton Goldman, called with the lighthearted report that many of his clients were interested in joining the party and he promised to send them over to lend a hand. On the appointed day as the clock tolled three, the doorbell rang and in walked Anita Loos, Lillian Gish, Helen Hayes, Garson Kanin, Ruth Gordon, Marian Seldes, Maureen Stapleton, and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. Just as the roles were being claimed, Laurence Olivier and Joan Plowright waltzed in and gleefully announced that they would take the roles of Higgins and Eliza. Midway through, once the cocktails had arrived and glasses had been sufficiently refilled, the cast decided to enliven the proceedings by reversing their roles to spectacular effect – for example, Olivier as Eliza and Plowright as Higgins. This started a tradition of non-traditional casting in the group. Other readings lured many other luminaries, including Louise Rainer, George Rose, Rex Harrison, Wendy Hiller, Denholm Elliott, Robert Helpmann, Roddy McDowall, Claudette Colbert, Elaine Stritch, and even Myrna Loy. The greatest gift of this, for me, was the lesson provided that there was no right or wrong, no one way to approach any artist’s work, and that Shaw’s plays were a living organism open to any artist’s interpretation. To blow the dust off traditionally Victorian staging of these plays with fresh approaches became one of my greatest joys while working with them. Though I was already a professional in the theater, having danced in the apprentice company of the Joffrey Ballet Company, studied cello with Rostropovich, and performed on Broadway, I had always assumed I’d one day be a part of running an arts organization, guided by Shaw’s belief that artists have a responsibility beyond themselves, that serving the community was part of the gift they were given.

What are the main differences between My Fair Lady and Shaw’s original Pygmalion?

People seem to love to compare these two works, which stand wonderfully on their own independent terms. It helps to remember that the brilliantly crafted musical My Fair Lady is based on Shaw’s Oscar-winning 1938 screenplay for the film and not his play. The musical meticulously follows the film’s structure. Journalists are quick to point out and scoff at the ending of the musical, in which Eliza returns to Higgins for a less ambiguous final fade-out. This is, in fact, one of the three versions of the ending written by Shaw. It wasn’t his first choice, but he didn’t have final say in the film’s creation. All that considered, the most powerful difference between the two are the portrayals of the two major characters. As usually played in the musical, Higgins is a harsh, aloof, judgmental, unkind man of advanced years. As Shaw imagined him, Higgins is a quirky and eccentric 40, deeply passionate and excited about his work. He has, however, used this obsession to hide from him emotional life, being afraid of having to deal with people, women in particular. He’s like a little boy with a tremendously fertile and imaginative brain but has limited social skills. He gives Eliza the tools to become the person she longs to be through education; Eliza teaches Higgins to connect to his own humanity and heart.

Eliza, as Shaw wrote her, is never a victim and very clearly is not looking for “someone’s head restin’ on my knee,” as sung in “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly.” She is no more than 20 and driven to rise in the world that has been closed to her given her socio-political circumstances. She desperately needs the tools to accomplish her dream of becoming “a lady in a flower shop.” She’s not looking for companionship and has absolutely no interest in dancing all night. She strives for the ability to create a life in which she can exist as a self-sustaining independent woman in a determinedly male-dominated society.

Using the title of the play, Pygmalion, as my guide in researching this work, I discovered that Shaw saw the Higgins journey as far more profound than Eliza’s. When we meet Eliza, she is already a fully formed, intensely bright and aware woman. All she needs are the tools of education to proceed. The Pygmalion myth introduces a brilliant sculptor in ancient Greece; afraid of life and connecting with anyone, he pours all of his passions into his work, finally sculpting the “perfect companion” in marble. Praying to the gods to bring her to life, they decided to have fun with him; they granted his wish, realizing that she would have her own will, her own thoughts, her own needs. This, they rightfully assumed, would force him back into the world.

Will your production be set in its original locale and will the cast be assuming English accents?

As Shaw’s Pygmalion is firmly set in London’s pre-WWI world, I’ve always felt the play resonates with its greatest impact by honoring that intent. So, yes, we’ll be telling Shaw’s story set in London, 1912, using all appropriate accents as he dictated.

Can you tell us a little about the set design and how you decided on it?

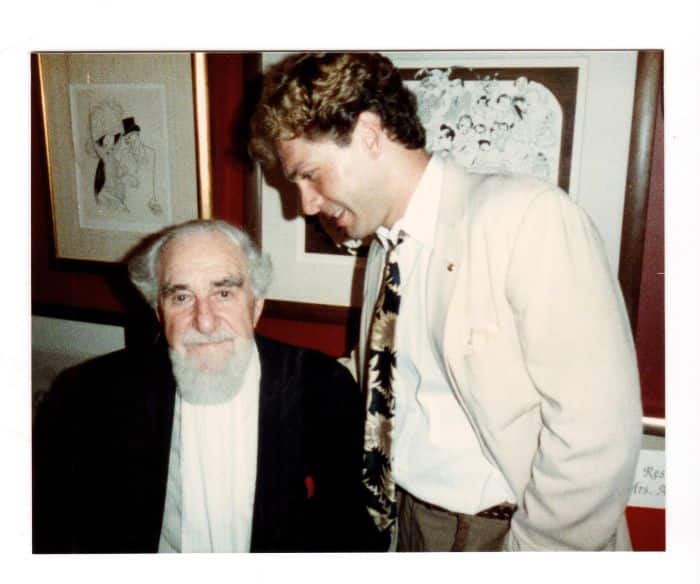

The brilliant artist, Al Hirschfeld, was a lifelong pal of mine. Our shared passion was George Bernard Shaw. Al relished Shaw’s work and activist humanitarianism, drawing images of Shaw throughout the many years. It was Al’s notion of one day designing a production of Pygmalion that haunted me over the years. So, when we decided to celebrate Gingold Theatrical Group’s 20th anniversary by presenting this play, the idea of celebrating Shaw through Al’s work became a joyous possibility. As a result, our scenic designer Lindsay Genevieve Fuori has created a set as if drawn by Al. So, we have the honor of partnering with the Al Hirschfeld Foundation, courtesy of their Creative Director David Leopold, to use Al’s work in the production and our key art! It’s a loving tribute to both Hirschfeld and Shaw.

What do you hope people take away from the show?

Shaw wrote this play as a form of self-analysis. As a poor uneducated kid in Dublin who was completely disenfranchised and unwanted, with a speech impediment, he escaped his dreary life at 19, to arrive in London to create a new world for himself. He was, in fact, like his Eliza Doolittle; he desperately needed a mentor, a Henry Higgins. Not finding one, he became his own Higgins. He self-educated, studied everything possible, and created a persona as a protection to feel more confident. He called his persona G.B.S., and eventually the man and the persona became one. This duality explains a great deal about who he was and how he created his works. It’s generally assumed he wrote the play for his beloved actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell, which is not the case. He was an incredibly clever businessman and wisely pursued her, as she was a great star on the London stage at the time. Once she accepted the role, he continued to adapt the play around her and it became a great success. But he created the play as a gift to us, as a reminder not to shut ourselves off from life, to keep our heart open and never to hide, either from the world or from ourselves.

Thank you, David, for giving our readers a sneak peek at Pygmalion. I look forward to seeing it at Theatre Row!

Pygmalion plays October 22-November 22, 2025, at Gingold Theatrical Group, performing at Theatre Row, Theatre 5, 410 W 42nd Street, NYC. For tickets (priced at $36.50-92.50, including fees), go online.