To inaugurate its new “Unplugged” programming – a format focused on simplicity in design to decrease production costs and to prioritize actors’ pay – Playwrights Horizons, committed to championing the voice of American writers, selected Jacob Perkins’ The Dinosaurs (originally commissioned by Clubbed Thumb during the pandemic) for a limited Off-Broadway world-premiere engagement directed by Tony nominee and multiple Obie winner Les Waters, whose approach is compatibly minimalist and centered on the cast’s performances.

Staged in a stark and simple meeting room illuminated with bright fluorescent ceiling lights (lighting by Yuki Link), with a folding table and chairs, a stopped clock on the wall (a visual clue to the show’s confusing inconsistency in time), a door marked with an exit sign, and a passage into an unseen adjoining room where supplies are stored (set by dots; props by Matt Carlin), a cast of six, dressed in casual everyday clothes that suit their characters’ ages (costumes by Oana Botez), enters one by one for a meeting of the “Saturday Survivors” – with the purpose to “stay sober and help other alcoholics achieve sobriety.”

In a program note, Perkins reveals his personal impetus for the play (the targeted homophobia of his hometown church in Appalachia that led to his excessive drinking) and its theme (a Saturday support group he later attended in a NYC church basement that resulted in his life-saving sobriety and a feeling of community). It’s an important message, though the presentation of its characters (all but one of whose names begins with the letter J – as does Jacob – and two of whom are named Joan/Joane) and their backward-and-forward chronological progression (with successive unbroken references by the same woman to widely different lengths of time she’s been sober), often seem gimmicky and unclear, without any transitions of scene, shifts in lighting, or changes of costume. Here, the minimalist approach is intentionally bewildering, leaving us to wonder if the narrative presented is a memory of what the group was over the years or an imagined idea of what it could be in the mind of Jane, who is the first to enter the room and silently stares off into the distance, lost in thought for an extended period, and occasionally hears the sound of chirping (sound by Palmer Hefferan), which, she acknowledges, may be in her head.

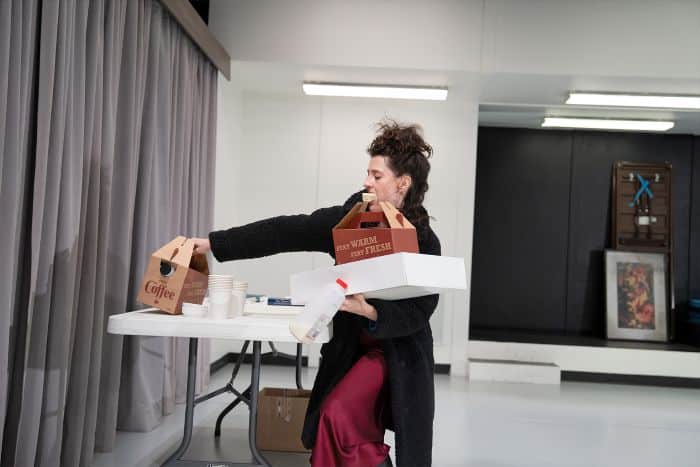

Much of the women’s conversation and action consists of laughably mundane talk (e.g., Jane and Buddy’s sudden understanding of the meaning of “Dunkin Donuts” and the compound word “cupcake;” the octogenarian Jolly’s mistaking the names of the women and using surprisingly foul and frank language about sex) and performing their “commitments” of setting up the room, coffee, and pastries, and looking for a missing coffee urn. There are nervous moments (Buddy, later wishing to be called by her given name Rayna, suffering from anxiety and leaving; the late arrival of Janet, which delays the start of the session – there are specific rules, timing, and topics for sharing) and tension (in their gossip about an unidentified teacher/friend and one of her 17-year-old students, which raises the issues of criminality and empathy). But as the show progresses, they become increasingly bonded and thankful for each other, come together in community and healing, recognize that the road to recovery is “not a solo journey,” and that “it always takes the time it needs to take.”

An excellent cast – April Matthis as Jane, Keilly McQuail as Buddy/Rayna, Kathleen Chalfant as Jolly and later as June, Elizabeth Marvel as Joan, Mallory Portnoy as Janet, and Maria Elena Ramirez as Joane – embraces the characters and delivers their distinctive personalities, voices, and demeanors, and, in the three longest monologues of the play, Janet shares with the group a cryptic dream of letting go, Joane a defining occurrence with her son that she never addressed with him again, and Joan her parents’ attitudes towards her. But the script’s overall lack of information about their backgrounds and the events that triggered their alcoholism is a hindrance to our understanding of them and the other characters, who would benefit from more fleshing out, to make them fully three-dimensional, comprehensible, and relatable to the audience.

In the end, we are left with many questions and few answers about their alcoholic motivations and the time-shifting narrative (near the conclusion of the play, Rayna sings “Who Knows Where the Time Goes”). But what we take away are women who “just wanted to be seen and heard and loved,” who are “learning to accept love and generosity,” and who, like the playwright, reaped the rewards of connection and support. And his program bio indicates that he has, since the original drafts and workshops of the play, experienced a catharsis through his writing about it, relocating again from NYC to Virginia to become a clinical mental health counselor and researcher, specializing in addiction and recovery in the queer and trans populations of Appalachia, where he grew up.

Running Time: Approximately 70 minutes, without intermission.

The Dinosaurs plays through Sunday, March 8, 2026, at Playwrights Horizons, 416 West 42nd Street, NYC. For tickets (priced at $63.50-103.50, including fees), go online, or find discount tickets at TodayTix.