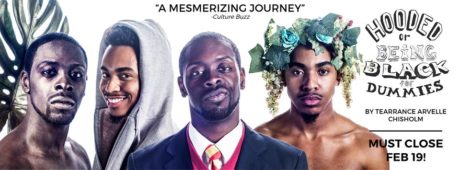

I first encountered Hooded, or Being Black for Dummies five months ago, when it was presented at The Kennedy Center’s Page-to-Stage Festival.

Hearing the play at that first public reading was an electrifying experience.

Now this dark comedy—the third in a series about coming of age in America—is having its world premiere as a fully-staged production at Mosaic Theater Company of DC. And it is even more riveting today as it descends, fully nuanced and multi-dimensional, through the layers of sitcom into an underworld that is mythic in its contradictions and conclusions.

While the previous plays in the series (Milk Like Sugar and Charm) focused on African-American kids living in urban settings—fenced in by poverty and bias—this one looks at the racial and cultural divisions that separate the worlds of the mostly-white suburb and the entirely-black ‘hood.

The play begins in the affluent suburb of Achievement Heights, where Marquis, an ambitious preppie, meets Tru, a presumed dropout from Baltimore. Both boys are African-American, but Marquis wears the uniform of privilege while Tru sports the outlier’s hooded sweatshirt.

Tru tries to straighten out his “white niggah” friend by writing Black for Dummies, a guide to behavior and speech in the “real” Black world. The manual, a guide to inner-city ritual and racial identity, is a mishmash of stereotypes, some hilarious, and some scary.

The production has the power of fireworks, exploding the complacency that has most of us—on both sides of the cultural border—locked in our own perceptions.

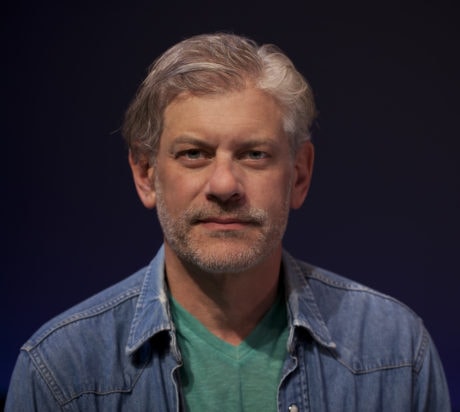

Curious to find out what went into creating this extraordinary production, I joined Serge Seiden, Mosaic’s seasoned Co-Founder and Director of the play, and Vaughn Ryan Midder, its Associate Director, at one of the final rehearsals.

Ravelle: What attracted you to this play?

Serge: I was drawn by its complexity, both in what it has to say—about growing up black in America—and by the difficulty of producing it so that the issues come alive.

On the surface, Hooded may look simple. There’s a cast of eight, a narrator—Officer Borzoi, a Simon Legree in blackface—and a handful of scenes. But it’s a huge show. There are many elements that have to be incorporated into the overall design to make it work.

In fact, it’s like a musical. There are major scene changes, dream sequences, fight scenes and love scenes, lighting and sound cues. Even the things that sound superficial—such as the surtitles and the video projections—are enormously complicated.

Technically, the play presents many challenges.

Thematically, the biggest challenge is establishing a balance between the comedy on the surface and the potential tragedy that’s just below.

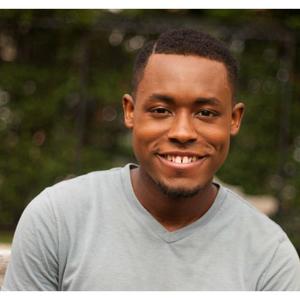

Vaughn: What drew me is the similarity to my own life, and to that of so many African-American young men. I can relate to both boys, since I’ve lived in both worlds. My parents were college-educated and I grew up in a beautiful, mixed-but-mostly-white town in Connecticut.

But when I was 14, we moved to Baltimore, to a neighborhood that was entirely African-American. So I experienced the same culture shock as Marquis. And I could have benefited from a guide like Black for Dummies, since I wanted to fit in, but didn’t know how to do it.

Have you worked together before? How did the two of you connect?

Serge: I’ve been been involved in theatre since 1988, and have been on and off stage—as a professional actor, a stage manager, a literary director and now managing director—ever since.

I met Vaughn when I was directing him in When January Feels Like Summer at Mosaic last year. I knew then that he was very talented. And I knew that I wanted to work with him again.

Vaughn: I graduated from the University of Maryland three years ago. Although I did some directing at The Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage, I thought of myself principally as an actor. But on the final night of When January Feels Like Summer, Serge took me aside and said, “You’re an amazing director.” It was a tribute I was not expecting.

A few months later, he called me in to do a cast reading of Hooded. I was so taken by the play—and by the extent to which it mirrored my own experience—that I asked for a directing job. And to my amazement, I got it!

How does the collaboration work?

Serge: Theatre is collaboration as an art form. We collaborate on everything. There’s no sense of “ownership” between us. Vaughn and I work together on every aspect of the production. Our job is to tease out what makes sense. And to trust our instincts.

Vaughn: Trust is the most important element in any collaboration. One of the greatest discoveries for me was finding that Serge actually trusted what I had to say. And I in turn have learned tremendously from him.

Does collaboration mean the prima donnas and impresarios of the past are gone?

Serge: Although there are still some theatres where prima donnas rule, Mosaic is not one of them. In fact, Hooded demanded more ensemble acting and design than most plays I know of.

Vaughn, what’s your take on the central characters?

Vaughn: I find the two mothers—one visible and one not—the most interesting.

The white mother, Debra, thinks of herself as a “white saviour.” She has adopted Marquis, an African-American child, but assumes that all other black boys are dirty and deprived.

She assumes that Tru, the inner-city black, is a high school dropout and the son of a single mother who works multiple jobs and is too ignorant to be a good parent. In fact, Tru’s unseen mother is really a hard-working woman who has raised a smart kid. And she’s probably married.

Marquis and Tru may sound like polar opposites, but in fact they’re just 14-year-olds. Tru has more street smarts, but he needs to learn a lot more.

In a way, the manual, Being Black for Dummies, is a rough draft. Both kids need to learn the rules of each other’s worlds. But even then, both will be subject to other people’s ideas about who they are, rather than their own.

Was there a lot of wizardry in this production?

Serge: This play demanded a lot of magic behind the scenes. We were very lucky to have Brayden Simpson as our chief magician and company manager. Brayden brought everything together, helping to bring Vaughn into the production and working with the incredible designers—David Lamont Wilson on sound, Brittany Shemuga on lighting and Ethan Sinnott on sets—who set new standards in collaboration.

Vaughn: Some people might be uneasy about the surreal moments in the play, the smoke and mirrors and noise and sheer physicality that makes much of the play so funny. But it’s the comedy—the ability to reach for laughs at the most awful things—that allows the conversation about race and identity to take place.

Serge, Looking backward—I know you went from politics to theatre, unlike our current national leader, who went the other way. How did that happen? And is politics still part of your life?

Serge: I came to Washington in 1985 to work as a legislative correspondent for Senator George Mitchell, but I had always found the theatre exciting and mysterious. When I mentioned this to my upstairs neighbors—the actors Isabel Keating and Michael Russotto—they suggested that I usher at Studio theatre, where they were both training. I did.

Two years later I quit my job on the Hill for a docu-musical called Dance Against Darkness: Living with Aids, produced by DC Cabaret. That led to a career in theatre, much of it at Studio.

I joined Ari Roth in the founding of Mosaic in 2015, with the express goal of combining my love of theatre with the pursuit of social justice. So yes, I’m still involved in politics, though practicing on a different stage.

Vaughn, Looking forward—You’ve just come off a major role in Milk Like Sugar, which is bound to reap awards. Are you still interested in acting? Or is directing your new career?

Vaughn: Right now, I enjoy both. I’ve just gotten my Equity card, and I’m very excited about what the future holds. Directing is more work—longer days, weeks and months—but it’s over once the play opens.

I’ve learned a tremendous amount from Serge, and am very grateful that I had the opportunity to direct a play that literally spoke to me from the heart, and echoed my own life.

Running Time: One hour and 40 minutes, with no intermission.

Hooded, or Being Black for Dummies plays through February 19, 2017, at Mosaic Theater Company of DC performing at the Atlas Performing Arts Center – 1333 H Street NE, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 399-7993 ext. 2, or purchase them online.

LINK:

Review: Hooded, or Being Black for Dummies at Mosaic Theater Company of DC by John Stoltenberg.

The play will have its world premiere in a fully-staged production in January 2017, when Mosaic Theater Company of DC will bring it to life as the fourth play of its second season.

The play will have its world premiere in a fully-staged production in January 2017, when Mosaic Theater Company of DC will bring it to life as the fourth play of its second season.