When Henry James wrote What Maisie Knew at the turn of the twentieth century, little did he dream that more than a century later it would form the basis for a screenplay that would speak with equally corrosive authenticity to filmgoers of the twenty-first. Although the latter part probably wouldn’t surprise the man who enjoined us: “Observe perpetually!”

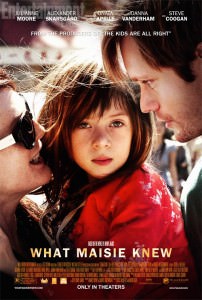

In Scott MacGehee and David Segal’s film of the same name, the eponymous heroine surely does, and tries to make sense of what she sees. What we see is that Maisie (the preternaturally adept and utterly adorable Onata Aprile) has had to inhabit two worlds, and—at least on the surface—has become skilled at navigating them. As the film begins, we see Susanna (Julianne Moore), a tenaciously ambitious, heavily mascaraed, fiftyish rock star still on the road whose glam days are more of a glimmer, gently lay her fully clothed daughter—socks and shoes included—on the bed to sleep.

At the child’s request, Susanna, eyes shining with maternal love, sings her one of her favorite songs as a lullaby. And we begin to realize, as Moore conveys with her usual raw and unapologetic, yet irresistibly appealing honesty, that while Susanna’s maternal skills are still embryonic, perhaps because she’s never given them a chance to fully develop, her love for her daughter is real. But so is her inability to connect it to, or to correct, her own behavior, seeming not to think how it might affect the child. Her art dealer husband Beale (Steve Coogan) is no better, but, given that he’s British, does it with a charming, cultivated accent.

We soon see that second world of Maisie’s when no one answers a persistent banging on the front door, and the sleepy six-year-old asking her mom for a lullaby switches swiftly to self-reliant, quasi-adult mode Her parents otherwise occupied, insulting each other in a loud, no-holds-barred argument, she scampers down the long flight of stairs to answer the door, then back up to retrieve and count out money (exact change, plus a tip) from her mom’s purse for the pizza delivery guy.

It is the quiet agony in her face as she watches them, half-hidden behind a door, that betrays the toll the thoughtlessly visceral, egocentric behavior of these nominal grownups is taking on their thinking, observant child. (Aprile’s performance chops have been justifiably lauded in just about every review of the film). She loves them, as they, in their way, love her. But not enough to consider what’s best for her, or to shield her from the worst in themselves.

There is a caring adult in Maisie’s life: Margo, her Swedish nanny (Joanna Vanderham). As luck (and lust) would have it, she is also young, blonde, and attractive, and quickly catches Daddy’s eye—and, soon upon, the man himself. As Beale and Susanna engage in ever more heated mutual accusations with divorce the inevitable next step, the child becomes a pawn whose affections are treasured possessions to be used as weapons. Margo, however, loves her for who she is. So although heartbreaking for the little girl, it’s not entirely untenable when Susanna loses custody, and Maisie moves in with Dad and Margo.

As the sages tell us, the only constant is change; thus, even this state of affairs (not to mention state of marriage) will have the half-life of one of Susanna’s party-ready false eyelashes: as honest as his affection may be at any given moment, Daddy is incapaBeale of commitment. Or forgiveness: when Susanna sends Maisie flowers, he disparages the dark-hued bouquet with visible distaste as “entirely inappropriate,” and slams it into the trash can. It is for Margo to comfort the grieving child by suggesting that she select a few of the flowers to press: You’ll have them forever.

Which is a good thing, in that Susanna’s reliability is about as ephemeral as the blossoms. On her first day post-divorce to pick up Maisie from school, she’s nowhere to be found. After a series of frantic phone calls, both Margo—who was on her way to the airport for a long-delayed honeymoon with Beale—and Susanna’s new black-T-shirted bartender boyfriend (no, wait! now new husband) Lincoln (Alexander Skarsgård), show up to claim the child.

Clearly, Margo can’t, and Lincoln… what school official would even think of letting a little girl go with a tall, blond, handsome young stranger—a bartender to boot—despite an aw-shucks, Gary-Cooper-like demeanor, complete with captivating smile? (Remember: this is supposed to be real life. Or an approximation thereof). But Margo’s done the necessary verification, or at least enough to allow her to feel marginally less of a heel for abandoning the tearful child, whose heartbreaking visage may well haunt her (already problematic) honeymoon.

If Maisie feels hopeless, Lincoln is, his contact with children apparently having ended with his own childhood: striding into the traffic and expertly dodging the oncoming cars, he realizes something—someone?—is missing, and looks back to see Maisie on the curb, waiting for him to take her hand. Lincoln will make up for his cluelessness by connecting with Maisie on a level her parents never did: playing games with her with the enthusiasm of a child, but the warmth and nonjudgmental patience of an adult.

This does not sit well with Susanna, who greets her daughter after every extended absence with exaggerated hugs, sloppy kisses and declarations of love that Maisie returns (or feels compelled to return), and seethes with jealousy at both Lincoln’s ease in showing genuine affection and Maisie’s spontaneous response. Feeling rejected, Susanna calls her daughter into the sound booth she’s set up and invites her to listen to her record a new song. The message is clear, and hits home: Maisie is mine.

That said, to her credit, and that of co-writers Nancy Doyne Carroll Cartwright and the seasoned directorial team of Segal and MacGehee—and of course, Henry James—in her better moments, Susanna recognizes and regrets her petty vindictiveness. Just as in his, Beale wants to be there for Maisie, and even proposes taking her with him to England, where he has decided to return. But neither of them has the strength of character to be capable of a long-term commitment, or to be accountable for a child they brought into the world, who wants only to be loved and valued, and to belong.

Two people do, though; and, through an improbable couple of coincidences that will prove providential, they will connect with each other as they have connected with Maisie. The film has more of a feel-good ending than the book. But perhaps the author would not have disapproved. “Sorrow comes in great waves . . . but rolls over us,” wrote Henry James, “and though it may almost smother us, it leaves us. And we know that if it is strong, we are stronger, inasmuch as it passes and we remain.”

Which Maisie learned; what Maisie knew.

______

Running Time: 99 minutes.

Rated: R

Playing at these DC area theatres.

LINK

What Maisie Knew website.

https://youtu.be/WQ5ea24Rn-A