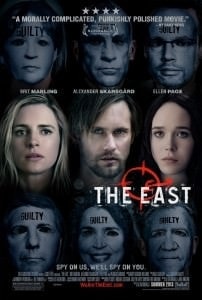

Georgetown Filmmakers Offer a Vision of Freedom

There is another way to live.

Page plays Izzy, a young woman who has traded the Ivy League and the life we all agree is so much to be desired for a pallet on the floor of an abandoned villa, a diet of discarded apples and carrots, and a purpose: to sabotage corporations that don’t mind poisoning the planet while they earn another billion dollars.

Someone has to do that work, but it wears Izzy out. You’d think, in fact, that Page had somehow increased the weight of the flesh on her face to make this movie: in every shot it sags with weariness. The corners of her mouth are always pointed down, and her eyes are always more open on the bottom than on the top. She moves and speaks with the measured energy of someone who expects to be exhausted for the rest of her life.

In a movie that’s fraught with anxiety, much of which swirls around Page’s character, that weary face is like a boggled sentence: it stops you, backs you up, and makes you ask, ‘wait, what?’

Betrayal, that’s what.

The weight in her face does not look like betrayal at first glance, or at second glance, and for a while you wonder where it came from. Devotion to lost causes? Rich-girl disaffection? You know that she’s chosen the life that she leads, which is a blessing in itself, so you’re inclined to ask where she gets off looking worn out by her blessings — would that all of us could live with such exhaustion!

But if you let your thoughts be guided by the immobility of Page’s face, especially as the story shifts into the phase that makes it most look like a thriller, you realize that you don’t want to share her weary plight — and that you share it anyway.

Betrayal is of course the stock and trade of thrillers. That’s what Sarah, the movie’s main character, does for a living: she infiltrates eco-terrorist groups, wins the confidence of their members, and then betrays them. Her real name is Jane, but Brit Marling plays her as a woman who’s not sure she wants to be her self, so even the film’s promotional material refers to her as Sarah. In the process of doing her job, Sarah realizes that the people she’s preparing to betray have been betrayed already — one of them is deaf, one of them is homely, two of them are gay — and that they’ve found a different way to live, one that deliberately increases the sense of vulnerability that conventional culture tries to eliminate but never does. They feed each other, they bathe each other, they dare to ask each other for exactly what they want. They practice rituals that have no purpose other than to make sure everyone feels vulnerable all the time.

Sarah falls in love with how they live, and so do we. That’s what makes the movie work so well. For Sarah it happens gradually, but for most of us it happens all at once, in the movie’s most beautiful scene, which is the scene when Ellen Page’s face comes to life.

“The way it works,” she tells Sarah, “Is you spin the bottle, and when it stops you ask the person it points to for something you want. If the person doesn’t feel comfortable with that, she might make a counter-suggestion. Like you might ask can we shake hands, and she might answer how about if we high-five?”

The requests are all the same: will you let me touch you in some way? Hugging first, then will you let me kiss your belly-button, then simply can we kiss. Once Luca makes the kiss request and it’s accepted, no one asks for anything else, because that’s what everybody wants. The version of this game we played as children skipped the request — you kissed the person that the bottle pointed to automatically — because we didn’t have the nerve to ask for kissing if the answer might be no. But this game’s purpose is to make you find the nerve.

When Izzy asks to kiss Sarah, whose loveliness is an oasis, her face shows hunger, and reluctance, and imminent exhilaration: her eyes lift and her cheeks lift and she’s ready. And after she has moved Sarah’s mouth toward the second stage of kissing integration, with a shift of the jaw that opens both of them a little wider, and makes Sarah pull away, the flicker you see in Izzy’s eyes is not affront, or rejection, but acceptance: she asked for what she wanted and she got as much as Sarah was prepared to give. No woman with the nerve to ask would expect any more or accept any less.

Nothing’s going to happen that you don’t want, they’d told Sarah, and they would make good.

When Sarah spins the bottle and it points to Benji, the charismatic leader she can hardly look away from, and when she makes the same request that everyone has made, we think that she’s about to get what Izzy wanted. But Benji knows how much can be surrendered in a kiss, and how much can be taken. When he asks if it would be all right if they just hugged, Sarah realizes that there’s really no protection.

Neither does there need to be. That’s the subtext written underneath the surface of this movie.

In an email explaining how the movie was born, Director and co-writer Batmanglij said that he and Marling spent a summer living vulnerably, in places beyond the pale that most of us will never see. “We encountered tribes across the country,” he wrote, “bands of young people living communally,… People who came from different places and had different backgrounds but believed in the power of the tribe.”

People who could no longer dwell even on the fringes of the culture that created Global Warming and the Great Recession, people who had made a culture of their own, who fed each other, bathed each other, dared to ask each other for exactly what they wanted.

“By the time Brit and I returned to LA,” said Batmanglij, “a fear in us had died. We weren’t afraid of how hot the kitchen gets, or of rejection, or of not being given permission.”

The last shot of Ellen Page’s face, when it’s nearly covered with dirt, looks like a warning about what becomes of people who say things like “nothing’s going to happen that you don’t want,” and believe them. That’s not true. It’s just not. But that’s no reason not to live as if it were. Batmanglij and Marling know that. Izzy knows it too.