No doubt about it: this is not your father’s (not to mention your English teacher’s) Shakespeare. Joss Whedon’s Much Ado About Nothing opens with a close-up of a man’s bare feet inserting themselves into his trouser legs. He glances over to the sleeping woman on the bed, her head turned toward the window, the small of her slender bare back visible beneath the covers. The camera cuts to a view of her face; as he tiptoes out, we see that she is awake.

The play’s actual opening scene, set outside Leonato’s house—Leonato, governor of Messina, is Hero’s father and Beatrice’s uncle—here takes place in a kitchen. The conversation between Leonato (Clark Gregg), Beatrice (Amy Acker) and the messenger is observed by Leonato’s daughter, Hero (Jillian Morgese), peeling potatoes by the sink as she helps prepare a meal, while Beatrice whacks away at a variety of veggies with a gleeful, almost vengeful determination.

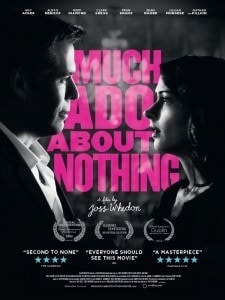

That last point is an eye-opener (pun intended) that makes Whedon’s Much Ado worth much ado by virtue of divergence alone. After his action-packed, color-saturated, Dolby Digital, Marvel Comics-inspired, $220,000,000 blockbuster, he shot the Shakespeare more or less on a lark, between contractual obligations, in black-and-white, in his own home, in less than a dozen days. Inspired by his longstanding love of the Bard’s words (he and his wife and co-producer Kai Cole have enjoyed holding Shakespeare readings with friends and colleagues there for years), Whedon invited a few of them plus some promising newcomers, and made a modern-day Much Ado on the fly.

Making it, financially anyway, “about” as “nothing” as you can get, for a feature film.

Fran Kranz’s earnest Claudio, whose palpable yearning for the fair maid is almost painful to watch, has so clearly given his heart over to Hero, we are not surprised when he falls for The Bastard (a Shakespearean wink, the name alludes to his illegitimate birth) Don John’s sinister machinations to convince him she’s a whore. (In what may be a Cole-Whedonian wink, one tense and ultra-masculine scene is shot incongruously in what must be their daughter’s bedroom, replete with ruffled bedspreads, pouffy pillows, dolls and stuffed animals; cameraman Jay Hunter also was DP for Whedon’s TV series Dollhouse).

Despite the ostensibly “retro” look of black-and-white, Hunter used a lightweight high-resolution digital camera to, alternately, achieve a searing intensity and clarity when focusing on faces (as with Claudio), or capture more informal moments with New Wave caprice. In one such memorable scene, Alexis Denisof’s Benedick, in “the lady”(here read: gentleman) “doth protest too much” mode, shows his comedic, balletic and calisthenic chops as he enumerates the indispensable and unattainable qualities a woman would have to possess to possess him, all the while jogging, running, leaping and bounding as he attempts to appear la-di-da nonchalant.

But as we all know, pride goeth before a fall: here, a literal one. The camera switches gears and begins following him in a hilarious tracking shot as, rather than effortlessly graceful, he suddenly resembles nothing so much as a character out of Commedia dell’Arte, tripping over his own feet, tumbling down inclines, bumping or banging into or wrapping his Gumby-like limbs around every stationary object in sight. It all ends only when he reaches the home’s sliding glass doors where, desperate to hear the conversation behind them, he grabs a large, leafy branch as (pricelessly unconvincing) camouflage.

For her part, later on inside the house, Acker’s Beatrice, as blasé as she would like to seem, is as risibly (and visibly) determined to conceal her feelings. Seizing a full laundry basket with cool detachment, intending to take it downstairs, she instead, in a Chaplin-worthy pratfall, takes a full header, landing at the bottom with an unseen (and at once cringe- and chortle-inducing) crash.

Nathan Fillion’s Dogberry, the malaprop-plagued police chief, is a delight—and a real change of pace for an actor whose most memorable roles include the one that earned him “critical acclaim and a large cult of fans” (per IMDb) as another sort of officer 1,000 years post-Shakespeare: Captain Malcolm Reynolds, in Whedon’s TV series Firefly.

In Much Ado About Nothing, his earnestness is of the loopy sort, his eyes attempting to register an intelligent intensity that is clearly beyond their reach. His partners in (ostensible) crime-solving, played by BriTANick’s “stupid video” meisters Nick Kocher as the First Watchman and Brian McElhaney as the Second Watchman (with whom Whedon would shoot a “bathroom video” after Much Ado; pun, er, not intended), add a fillip of silliness to the mix.

That being said, for all the humor in the film (including at the masked ball: when Beatrice declares, “We must follow the leaders,” she joins a conga line), it’s the moments of dramatic intensity that register most memorably. In addition to Kranz’s earlier scene, his Claudio, in the climactic Act IV confrontation-accusation-repudiation scene, shocking in its ferocity, joins with Morgese’s Hero to draw the audience with almost physical force into their narrow orbit, linked by despair and anguish as they are torn apart by treachery and lies.

Whedon and Hunter masterfully, unapologetically pull out all the stops here, framing and lighting the faces in a style reminiscent of Huston, Preminger, Walsh, et al. (In an interview at SXSW, Gregg called the film “an artful, fast moving, sexy noir version of Shakespeare”).

Then Beatrice, having just, against all reason and expectation (both hers and ours), sworn her love to the Benedick she’s been mocking, chiding and avoiding, demands that he avenge her cousin—and he refuses. Acker’s up to the task—angry, stricken, disbelieving, grimly determined—the complexity of her emotions almost palpable as they flicker across her face. The one thing she doesn’t do is cry. But you might.

Whedon and Hunter are equally up to the task. Including the music, which Whedon wrote in his first foray as cinematic composer, backed up by Clint Bennett (who also was music editor for What Maisie Knew, reviewed here last month) and ASCAP Award-winning composer Deborah Lurie. The score is a pleasingly eclectic mix of the classically lyrical, the catchily contemporary and melodic, and (from Whedon’s brother Jed) the groan- and grin-inducing “needledrop” moments that pop up along the way.

The film, too, succeeds as a whole in mixing film and stage eras and genres, employing a classic black-and-white to bring to the screen a late Renaissance play whose actors include several schooled and experienced in Shakespeare (Denisof trained in London and appeared in Hamlet with the Royal Shakespeare Company, while Acker was a Hero early in her career) playing familiar characters who use iPhones to spy on one another.

No, not your father’s Shakespeare. On second thought, though, your English teacher, even if a purist, might not regard it with the “jaundiced eye” made famous by the Bard’s compatriot poet, the estimable Mr. Pope. Who knows? She might even find in it a “brave new world” in interpretive theater, while students, past and present, who’ve given him “short shrift” may suddenly find Shakespeare… sexy. If they do, that will be much ado about something that will remain with them far longer than this film. And Joss Whedon and company will have helped them get there.

Here are DC area showtimes.

Running Time: 109 Minutes.

Rated: PG-13.

LINK

Much Ado About Nothing website.