The Book of Mormon… CONTAINS HERESY. That’s not a preshow advisory you’ll find posted at The Kennedy Center where The Book of Mormon is playing to standing-room houses. No, it’s my alert to you, dear reader, about what follows. Because instead of rehashing what most everyone knows—that this show is outrageous, hilarious, and the best Broadway musical in years—I’m going to take this show seriously. Meaning: I’m going to look at The Book of Mormon as one of theater history’s most significant contributions to global understanding and world peace.

That was not a joke.

I had questions on my mind when I went to The KenCen the other evening. I’d read a lot about the show. I’d listened and relistened to the cast album (which completely cracked me up). And what I wanted to understand was this: How the heck did they do it? How did they get away with it? By what sorcery did Trey Parker, Robert Lopez, and Matt Stone (who created book, music, and lyrics) alchemize this material (ostensibly offensive to mainstream Muggles) into abracadabra box office? Really, these three should write a book called Secrets of Highly Successful Subversives.

Then as I watched, something unexpected started to occur to me. I began to see that what’s most unconventional about this show—what’s most dangerously antiestablishment, actually—is not its rude, crude, and lewd humor. It’s what the show says about religion and belief. And not just what it spoofs about Mormonism—that’s but the setup, the pretext, a part representing the whole. And not just its gleeful blasphemy—starting with the fourth song in Act One, “Hasa Diga Eebowai,” which means “Fuck you, God.” The truly incendiary importance of this show is the brilliant blaze of light it casts on the entire human history of faith on earth.

I went to seminary before I did grad work in theater. As a result I have a Master of Divinity degree, which sounds like a black belt in holiness (but I assure you it’s not). At the time I was keenly interested in religion (though not as a believer) and connections between theater and theology—which may account for what dawned on me my night at the Opera House and prompted this exegesis. (That’s a fancy-schmancy way of saying “explanation and interpretation of a religious text.” And yeah, you read that right: I now take the musical Book of Mormon to be a profound religious text for our times).

There’s a trenchant storyline running through The Book of Mormon about how what passes for divine revelation is really just some stuff some humans made up. At the beginning the show pokes fun at the dodgy origin story upon which the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints was founded. One can readily guess what a giggle this is for non-Mormons (not a few of whom, let it be said, harbor an unseemly sense of superiority about the divine authority of their own scriptures and creeds). But Parker, Lopez, and Stone’s potshots are all lobbed so affectionately and knowingly that even devout Mormons can be amused. (Plus, judging from the three full-page paid ads in the slick Playbill promoting thebookofmormon.org, LDS officials can’t be too miffed).

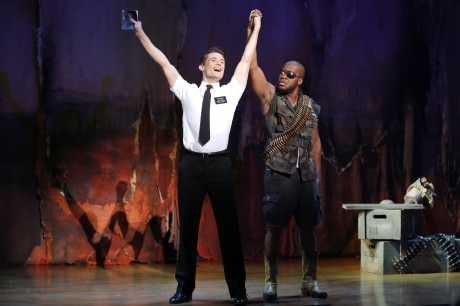

Then that storyline takes a turn in Act Two that is stunningly ridiculous and sublime. Elder Cunningham (the gifted buffo Christopher John O’Neill), whom we know to be a fibber, has been dispatched with a buddy, Elder Price (the hotshot hoofer Mark Evans) to Uganda to score conversions for the Mormon missionary team. Cunningly, Elder Cunningham revises the Mormon scriptural narrative to be more relatable to the residents. Actually he flat-out makes stuff up. Throughout the show, Parker, Lopez, and Stone borrow shamelessly from movies and other Broadway musicals, so it comes as yet another pleasure when there’s a play within the play reminiscent of the The King and I’s “Small House of Uncle Thomas” reenactment. Performing before the young missionaries’ visiting supervisor, a troupe of villagers act out a wackadoodle version of the Mormon origin story that was completely fabricated by Elder Cunningham. The supervisor is scandalized—until it becomes clear that Cunningham’s rewrite has wrought amazingly beneficial effects. It has improved people’s lives. It has given them hope and meaning. It has delivered clear-cut ethical precepts that put a stop to horrific behaviors. (I’m being vague here in case you’ve yet to see the show). In short, Elder Cunningham’s transparently fictional religious myth helps make humans more humane to one another.

Looked at as a parable within a parable, that twist in the story points to the show’s prophetic insight, for The Book of Mormon musical holds up for all to see how none of the narratives that undergird faith actually descended from on high. None. They were all stories told by humans to give expression to and embody aspirations for a good life. This message about sacred theistic storytelling that Parker, Lopez, and Stone have given us through the profane storytelling medium of theater is, in my humble estimation, a world changer. It tells us—even more eloquently than John Lennon’s “Imagine”—that though all religious stories seek truth, none is “the” truth. None are literally divine revelation, not one of them; all are human-made figures of speech; all ultimately have validity only in what can be observed as their moral influence on how well humans get along. Ergo, waging holy war is futile and religious bigotry is dumb, for the unprovable cannot be proved, the unclaimable cannot be claimed…and the ineffable cannot be eff’ed.

That the audience the other night was getting a bit of this radical message was evident when a character called an obvious fiction “a metaphor” and the line got not only laughs but resounding applause. That’s when I realized I was learning a real lesson about how highly successful subversives do heresy in hilarity: Seriously. And not seriously. And at the same time.

LINK

Amanda Gunther’s review of The Book of Mormon on DCMetroTheaterArts.