“I am Nijinsky,” says the actor/dancer Primož Bezjak, in a tone almost primal. “The great Nijinsky.”

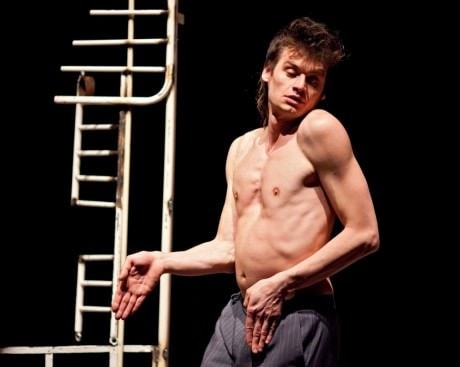

He speaks in Slovenian as his words appear on overhead screens in English. He has been sitting onstage in silence as we entered the space and took seats around a constructivist circular playing area. For some moments now, this danseur noble‘s supple and sinewy body has been moving, slowly, beginning to burn images of torment and grace into our brains. When at last language leaves this seeming shaman’s lips, we the opening night audience are already transfixed—as though, uncannily, we have entered a trance state. For we are beholding a performance so magnificent that one barely dares breathe.

At the end of our fleeting hour in this presence, we sit in rapt awe. We have just been led on a stream-of-consciousness trip through the troubled life and disintegrating mind of the lithe young man who was the dance legend Nijinsky, by an exquisite guide who glides in and out of embodiments of dramatic personae from Nijinsky’s dark inner life. As boldly portrayed by Bezjak, the great Nijinsky has come to life before our eyes, exhibiting moves choreographed by Mateja Rebolj as if channeling “the God of dance” himself. (There were no grands jetés, through which Nijinsky created the illusion he was suspended in midair—they would have been hazardous in this low-ceilinged space—but Bezjak left no doubt he could have executed them beautifully). Then Bezjak stands on stage out of character and—breaking his own mesmerizingly self-absorbed concentration—acknowledges for the first time our presence. As if on cue we come to and we remember: Oh right, this is where we applaud. And suddenly we do so, Thunderously. Still transfixed by what has transpired.

This remarkable production by Slovenia’s Mladinsko Theatre has come to town for five nights only at Mead Theatre Lab at Flashpoint, presented by CulturalDC, after which the company has tickets to fly back home. That means this Last Dance is DC’s last chance to witness a rare theater event. First seen at Signature Theater in 1998–99, Nijinsky’s Last Dance,by local playwright Norman Allen, has had several productions—but I cannot imagine any as fine as this.

Allen’s script is based on the diary Nijinsky wrote in a manic six and a half weeks that began the day after what was literally his last dance (a fiasco). By that time, at age 28, Nijinsky’s brilliant career was over, and he had been diagnosed as mentally ill. The diary tracks, surreally, Nijinsky’s memories of pivotal events and influential people even as he enters into the schizophrenic mental state for which he would be institutionalized the rest of his life.

Barbara Kapelj Osredkar’s set design and Matjaž Brišar’s lighting design have created an environment of confinement—a sunken, square, cagelike space, fitted with mangled sanitarium bed frames—surrounded by a raised playing area on which Nijinsky’s recollected triumphs take flight, and anguished scenes return, accompanied by Silvo Zupančič’s cerebrally disturbing soundscape.

One need know nothing about Nijinsky’s biography to appreciate Nijinsky’s Last Dance, but knowing even a bit makes the experience richer. One of the major themes in Nijinsky’s life was the persistent disconnect between his own sexual desires and the ways he was desired; rarely did they sync. As a youth he was an avid consumer of prostituted women. At the age of 18, androgynous and poor, he met an older man, a wealthy prince, who became his first sugar daddy with benefits. (In the jarring jargon of today, Nijinsky was straight and ‘gay for pay’). After a year the prince tired of Nijinsky and handed him off to SDWB #2, another older man, the wealthy impresario Diaghilev, who was to shape and exploit the career for which Nijinsky became renowned. For his part, as he records in his diary, Nijinsky was repulsed by Diagilev’s flabby butt and saggy moobs and disliked coming upon pillows soiled with Diagilev’s black hair dye. At one point the creepy Svengali loaned out his boytoy to pose nude for the sculptor Rodin, who promptly exacted his own priapic quickie.

The spiritual and emotional impact on Nijinsky of all this craven sexual usage becomes excruciatingly transparent in Bezjak’s dextrous portrayal of an introverted, lonely soul who has no soulmate. Nijinsky’s own choreography—scandalous for its time—notoriously included autoeroticism, which Bezjak does not shy from, and which even now comes as a shock. It’s as though through this performance Bezjak shows us, from the raw inside out, precisely how it feels never to feel one’s body belong to oneself because it has been a commodity for so many others.

When Nijinsky fell rather abruptly in love with, and married, a wealthy woman who had been a groupie (and who later bore him a daughter), the jealous Diagilev spitefully paid him back by severing their professional ties—a move that proved calamitous for Nijinsky’s career and hastened his descent into the agony where Last Dance begins. In this singular new staging, Director Marko Mlačnik has created an evocative and original landscape and found exactly the perfect performer to travel it. Mlačnik and Bezjak’s collaboration brought to mind for me the stage work done by the influential Polish theater director Jerzy Grotowski and his premier actor Ryszard Cieslak. If back in the day when I saw their extraordinary work I thought, “I’ll never see anything like this again,” I was dead wrong.

Nijinsky’s Last Dance plays through this Friday, August 30, 2013 at Mead Theatre Lab at Flashpoint – 916 G Street, in Washington, DC. For tickets, purchase them online.

LINKS

There is no film record of Nijinski dancing, but this video, computer-animated from actual stills, offers a shadowy glimpse.

https://youtu.be/N7fIGEPZarI