“Thanks for sharing,” most commonly considered a wry reply to one who’s just told you something you really didn’t need to know, is both apropos and perplexing as a title for a film whose characters really don’t want to share the depths of what the average person might call their personal depravity, yet are so tormented by their obsession as to arguably render that breezy reduction of their affliction a gratuitous kick in the—er—tender parts.

The film itself balances these two sometimes opposing, sometimes complementary perspectives with varying degrees of success. The earnestness and painful humor of veteran screenwriter (The Kids Are All Right) Stuart Blumberg’s directorial debut find their most potent expression in the dynamic performances of some of the cast members. Among them is a surprisingly compelling turn by one whose own debut here as an actor easily matches the overall impressive work of the all-star cast of film and Broadway vets in intensity and impact, and marks her as someone to watch should she decide to permanently add acting to her vita.

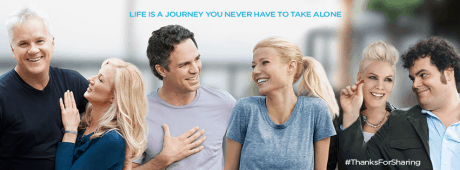

Home base for the ensemble of characters is an encounter group whose members come together to share their progress (or lack thereof) in overcoming their shameful compulsion, described by one as “like tryin’ to quit crack . . . while the pipe’s attached to your body.” This would be Mike (Tim Robbins), a small-business owner whose determination to gain self-control will spill over toxically into his relationship with his wife and son.

Mike is Adam’s sponsor; Adam is Neil’s. And three more different personalities could not—conveniently for the script, but nonetheless, not completely improbable—be found. Adam (Mark Ruffalo, from Kids), an environmental consultant who fears even to dip his toe in the heretofore restricted waters of relationship possibilities, has by far the tougher assignment: Neil (Josh Gad, of The Book of Mormon and 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue) is an ER physician who’s developed a new implement for doctors of voyeurism, devoting some of what he may have learned in med school to developing a sophisticated shoe-cam that can see up his boss’s skirt. The sack time he thereby earns is not, need I say, of the sort he was looking forward to. (If in his dreams).

A large man whose lack of any semblance of self-discipline is manifested in his apartment’s Early Garbage Dump décor and his doughnut-gorging—not as compulsion substitution; his video collection still gets him in regular touch with his little friend—Neil (Josh Gad) will find an unlikely soul mate in hair stylist Dede (Alecia Moore), a young woman whose white hair is emblazoned with a blue streak, and who will tell the group that she has been a sex addict since the age of four. “There has to be another way,” she says to them, in a moment that goes straight for the gut, and hits it squarely. “There ‘s fucking gotta be,” she adds quietly, “or I’m gonna kill myself.”

Adam’s phobia-fatal siren song will be sung by Phoebe (Gretchen Paltrow), a breast cancer survivor whose fears are as real as his, but who has found a way past them by becoming a runner, and is now training for a triathlon. Their attraction grows; it seems pure, and warm. When she asks him if he’s an alcoholic, his face is an Actors Studio panoply of conflicting, quickly shifting emotions; Ruffalo is masterly here. We watch as his feelings of doubt begin to slide, slowly and inexorably, towards hopelessness, as she tells him that because she was married to an alcoholic, she promised herself she’d never date another addict.

And Mike, the putative “wise elder” of the trio? Mike’s marriage to Katie (Joely Richardson) is a good one, having healed—or so Katie thinks—from the gashes that Mike’s alcohol-fueled violence and infidelities inflicted on it. But when their estranged son Danny (Patrick Fugit) breaks into their home in the middle of the night to get food from the fridge, all of the repressed anger bubbles to the surface, and will explode in a shattering dénouement that could destroy the still-fragile structure that Mike has worked so hard to rebuild.

The characters deal with their individual addictions in ways that are by and large true to each one’s personality and character, whose facets, as in life, are revealed slowly. Danny tells Mike he broke his drug habit on his own (“Not everyone needs AA, Dad”); their relationship, pocked with wounds that have been covered over but haven’t healed because they’ve never been cleaned out, will veer from affectionate father-son banter to a frightening release of long-simmering fury.

Neil, on the other hand, becomes what Dede calls “like an open wound” when he confesses his failures to the group after being raked over the coals by Adam for not having maintained his diary. “I need help,” he tells them softly, his voice cracking. Here Gad and Moore (otherwise known as the multi-platinum recording artist “P!nk”)—who observes him with compassion, understanding and, what the expression in her eyes makes searingly clear, a very plugged-in pain—provide a look into the strong, healing links that can be forged between broken people.

Ruffalo’s Adam is very vulnerable, very believable, and gets to expound some of the encounter-group industry’s best lines. Visiting Mike, he starts chatting up the sorrowful-looking painter working on the house, who tells Adam he’s been crying. “Feelings are like children,” the immediately sympathetic Adam responds. “You don’t wanna stuff ’em in the trunk, but you don’t wanna let ’em drive the car, either.”

Danny decides he wants to build a koi pond in the back yard, and while initially, instinctively dismissive, Mike—at Katie’s urging—starts helping him dig it. Inside the house, another worker explodes and begins destroying the wall he’s just built, having taken offense at an offhand remark of Mike’s. Mike and Danny calm him down, and quietly take him outside.

In what may have been a quick cut to a scene that didn’t naturally flow from this one (or the equally likely possibility that your reporter missed writing it down), we see father and son alone in the car, slaked by driving sheets of rain. Danny apologizes to Mike for stealing and lying, apparently a pattern he has fallen into over the years. Here the camera’s focus on the faces is intense and unflattering; the actors’ willingness to expose themselves and the sheer nakedness of their characters’ emotions makes them their own, drawing the viewer into their tightly held, but now, ever so slowly, ever so reluctantly emerging pain.

And Adam discovers that he can start to let his own go, but—as life would have it—at just about the moment he allows himself to believe himself not only capable, but worthy of love, Phoebe will find that his deception makes him undeserving, at least of hers. This is not the last challenge their relationship will undergo, tho it feels irreversibly final at the time. (Don’t they always?)

As will the other relationships, whose currents will alternate as swiftly and unpredictably as those of Danny’s koi pond. The depressed, unemployed Neil, sitting gloomily in T-shirt, undershorts and stubble-covered chin, will get a call from Dede that changes both of their lives. In one scene, when Dede takes Neil to a dance class, as he hesitantly takes her into his arms, his face begins to take on a handsomeness, a quiet warmth and glow, we’ve never seen before.

Adam and Phoebe will have it out, and weigh their options; at one point, at a restaurant, an old girlfriend who clearly still has the hots for him spots him, and, ignoring Phoebe, tries to come on to him. The tension and discomfort are palpable; again, a tribute to skillful acting, direction, and camera work.

Their discomfort is nothing compared to what’s happening over at Mike’s house, where old resentments, suspicions and antagonisms are having it out in a far more tangible way, and the differences—in both senses of the word—between father and son slam smack into their essential, uncompromising similarities. (Incongruously, for all the film’s success in realistically portraying emotions, we next see Mike with not a mark on him.) Richardson, who in prior, mostly fleeting scenes has movingly rendered Katie’s grit and resolve tempered by a a resolutely coping good humor, here owns the scene, the camera, and her character’s life.

This being a Hollywood film, little, if anything, is left unresolved. But Thanks for Sharing is a film with much worth sharing; one whose acting, directing, and camera work is worth sharing your time with.

Running Time: 112 minutes.

DC area showtimes can be found here.

LINK

Thanks for Sharing website.

https://youtu.be/8XERKbqjx6w