A sizable crowd at Legacy and Life: A Musical and Visual Reflection greeted the Choral Arts Society of Washington’s performance of the Requiem by Giuseppe Verdi and Take Him, Earth by composer Steven Stuckey: about 2,000 of the Concert Hall’s 2,400-some seats were occupied, with even the top-tier level offering visual evidence of audience presence at various points around the enormous horseshoe, as heads, arms and elbows jutted out at intervals as people found and settled into their seats.

For all its size, the crowd, at least an appreciable part, was au courant on the local classical music scene, an almost unified sharp intake of breath greeting WETA FM’s Deb Lamberton, who came onstage to introduce the program. Lamberton, genial, and gracious, gave special attention to the first piece, written to honor the life and legacy of President John F. Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his assassination, and having its East Coast premiere here. It was a wise move on The Kennedy Center’s part.

Unknown to most and, on first hearing, occasionally challenging to the ears and musical sensibilities of those who came mostly for the Verdi—among them, it must be confessed, this reviewer—Take Him, Earth takes its title from a verse by the 4th-century Roman Christian poet Aurelius Prudentius Clemens. It was originally set to music in this context by Herbert Howells, the composition commissioned in the aftermath of Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963.

But that is just the germ of the work. The Pulitzer Prize-winning, Grammy-nominated Stucky, one of the most frequently performed of contemporary classical composers, has also taken verses by Aeschylus—the anguished nobility of the one many of us learned after the assassination of the President’s brother Bobby, who had cherished it; and Shakespeare—Juliet’s “When he shall die” invocation to the night—to honor not just the memory, but what Stucky believes to be the enduring legacy of the slain president.

Written for chorus and a small complement of strings, plus flute, oboe, clarinet, and horn, the piece is a study in contrasts that is, for this listener, intermittently effective in supporting or suggesting the sense and emotion of the three texts. It begins with the clarion call of a horn, followed by a commotion of instruments that evokes the chaos of battle, actual or internal. The choral entrance that follows is so gentle as to be almost inaudible; when it becomes clear, we realize that it is tonal, harmonious; it sets us back, relieved, and quietly moved.

The piece moves, too, back to the atonal, with the lines, “Body of a man I bring you/ Noble even in its ruin,” becoming impassioned with the refrain “Take him, Earth.” The rest was somewhat difficult to follow, seeming to move among the verses without the aid of the sort of melodic or harmonic “cues” prevalent in the classical canon. The chorus, which did a yeoman’s job musically, had an understandably hard time articulating some of the text: much of the music moves rapidly, and is spiked with unexpected fits, starts, and sharp exclamations (including at least one shriek). It ends, though, on a note that is at once meditative, and quietly chilling; indeed, a single note, the chorus singing in hushed tones the final line of the Prudentius: “Grave his name, and pour the fragrant/Balm upon the icy stone.”

Hushed tones famously begin Verdi’s beloved Requiem, which also received a special introduction, this one by the program’s conductor, Choral Arts Society Artistic Director Scott Tucker. Tucker reminded us that 2013 is also the “Year of Italian Culture” in the U.S., as well as the 200th anniversary of Giuseppe Verdi’s birth, making the Requiem the ideal principal work for the program.

The choice was whether to present it as a “museum piece,” in its own “bubble”—which Tucker quickly assured us would have been more than sufficient in ordinary circumstances, given its sheer magnificence—or to present it in context of the anniversary of President Kennedy’s death. Verdi did write it, Tucker reminded us, as a vehicle for public mourning and appreciation for the poet and playwright Alessandro Manzoni—not quite a president, but a national figure nonetheless. (And one, according to Wikipedia, whose remains, “after lying in state for some days, were followed to the Cimitero Monumentale in Milan by a vast cortege, including the royal princes and all the great officers of state”).

But it is the legacy of President Kennedy: his unwavering commitment to the arts—memorialized by the Kennedy Center itself, and by the many plaques, engravings, and artworks throughout the building—that has continued to inform the nation’s culture, and that formed the nucleus of the program. Having said that, Tucker acknowledged the potential heresy inherent in what we were about to see and hear. “If you’re a purist,” he told us, “I empathize,” being something of one himself. “But I hope you’ll give this a chance.”

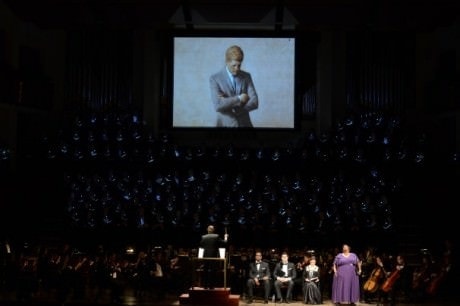

The staging for this Requiem was multi-level: above the orchestra onstage, a large video screen nested within the top three rows of the eight- or nine-row, 170-member chorus. As the music proceeded, images of Kennedy’s life flashed upon the screen, some filmed, some photographic, the photos at times in a moving or stationary collage. While at first irritating, they would gradually become only selectively so, and even once or twice, affecting when they illustrated a moment in Kennedy’s life, or the life of the nation, that the music seemed to speak to.

Standing in the darkness but for three spotlights at the top center of the ceiling, each lit by a small electric candle held in the right hand, the chorus sang with passion and conviction, joining the orchestra for a full-blooded, thunderous “Dies irae” (Day of Wrath) as contemporary and contemporaneous photos of war, protest, and the Berlin Wall filled the screen. To give the audience’s eyes and mind a rest, the image flow stopped at intervals for shots of the singers and soloists, interspersed with text.

But now, to the most important part of the performance—the music. The “Cuncta stricte discussurus” (To weigh man’s deeds in each detail) ending the fiery “Dies irae” was frighteningly whispered, the singers convincingly terrified, the sentiment skillfully conveyed both facially and vocally, before the fate awaiting those in dread of the final judgment. The “Tuba mirum” (The trumpet, scattering a wondrous sound) was deeply stirring, the horn players illuminated by tiny lights and standing like sentinels, ramrod-straight, in the boxes at top right and left of the stage as they sounded the “trumpet” that would “gather all before the throne.”

The soloists were of varying quality. Bass Kevin Maynor excelled in the lower register, the dark, rich timbre of these notes contrasting with the more tentative, almost swallowed quality of some of the upper. Mezzo soprano Géraldine Chauvet exhibited a controlled, shimmering vibrato, especially effective in the concluding “Nil. Nil. Nil inultum remanebit” (Nothing. Nothing. Nothing shall remain unavenged).

Soprano Jonita Lattimore’s gentle, soaring, crystal-clear high notes graced the “Quid sum miser” (What shall I, wretch, say?), as it did in a couple of other places where a soprano’s pinging “head voice” brings exquisite chills, particularly the much cherished—and equally dreaded—climaxing high C of the word “Requiem” (Rest) preceding the final repeat of the “Dies irae.”

Projection was also lacking at the start of the soprano-mezzo duet “Recordare” (Remember), but picked up about midway through. The same could be said with regard to tenor Patrick O’Halloran, much of whose “Ingemisco” (I groan) would also have benefited from some head voice. By the time he got to “Ne perenni cremer igne” (Lest I burn in everlasting fire), though, he was sounding more confident, ending with a ringing “in parte dextra” (on Thy right hand). Halloran would excel in the “Offertorio” quartet, his pianos a gentle prayer.

The bass “Confutatis maledictis” (When the damned are sentenced) suffered from mushiness and imprecise diction, but was the point at which the visuals, which had temporarily ceased, resumed with video clips of John and Jacqueline Kennedy arriving in Dallas and being greeted by Texas officials. With a terrifying, explosive recapitulation of the “Dies irae,” came the Zapruder film—but only up to the frame in which the fatal shots are fired, leaving the audience to imagine the irrevocable horror that would forever mark an era and a generation.

With the “Lachrymosa” (Day of weeping) quartet came the motorcade; the “Pie Jesu” (Merciful Lord), a clip of little John-John sobbing, unbearable in its own right, but excruciating when accompanied by the Verdi. The sudden shift in mood to the cheery, bouncy “Sanctus” (Holy) brought the iconic photos of Kennedy playing with his children, artfully arranged to give the impression of photographs being dropped into an album, the singers bringing a bright, sunshiny sound to the opening choral arpeggio.

The “Agnus Dei” (Lamb of God) brought sailing photos of Kennedy and the water he so loved, and the words he would use—“We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea, whether it is to sail or to watch, we are going back from whence we came”—to describe his intimate relationship with it. At its end, the “Dona eis requiem sempiternam” (Grant them rest eternal), the rolling waves were seen first from the shore, then from Kennedy’s perspective as he waved to them, then with him in a sailboat, smiling contentedly, the boat bobbing rhythmically in the waves.

The “Lux aeterna luceat eis” (Let everlasting light shine on them) opened upon the words from a speech in which he vowed to put a man on the moon, and photos of the spacecraft piloted in 1961 by Alan Shepard and the next year by John Glenn. Closing that section, the “Et lux perpetua” (And let everlasting light) filled the screen with some of the few color shots, these of a starry sky and endless cosmos, the sudden contrast and picture quality thrilling in both clarity and intensity.

As Lattimore concluded the “Tremens factus sum ego et timeo” (I am seized with fear and trembling) with another exquisite pianissimo, there was a portentous silence as she looked apprehensively over her right shoulder. Leaving just enough time for the audience to begin growing nervously impatient for what it knew was to come, Tucker suddenly slashed the air with his baton, and the merciless, ear-splitting crash of the final, explosive “Dies irae” enveloped the hall. And when Lattimore again, and for the last time, uttered the high C of her softest, consummate “Requiem,” it quivered, almost threatening to break. The requiem ended—as it had begun in a high whisper—in a low, quiet murmur.

The film collage had come to an end considerably before. And while it had done its job, often well and even memorably, its absence, in the face of Verdi’s timeless musical and emotional richness, was hardly noticed.

The audience sprang to their feet, about half immediately, most of the rest soon after, for a rousing and heartfelt standing ovation, followed by two curtain calls, the chorus receiving the most enthusiastic applause and cheers. Conductor Scott Tucker also came in for a good portion, and well deserved it was. He had led the orchestra and chorus with a keen musical intelligence, the players and singers, including soloists, generally attentive to his precise beat and expressive gestures.

Was it a perfect Requiem? No. Was the blending of it with quotes, photos and video clips entirely successful? No again. Was it a musical memorial that did honor to the life and memory of a beloved president who was slain, and died much too young, and a much-loved composer who lived twice as long yet, whose music, like the eternally youthful John Fitzgerald Kennedy, shows no signs of age? Here, your reviewer would say: yes.

Her only partial regret was that no mention was made of the anniversary of another significant, tragically portentous date. Exactly 75 tears ago—two days, actually, November 10-11, 1938, paralleling the unusual (no doubt because uncertain) two-day birth date of the composer cited in the program, October 9-10, 1813—the Night of Broken Glass, or Kristallnacht, was perpetrated against Jewish-owned businesses and synagogues, marking the beginning of the Holocaust.

Five years later, in Terezin, one of the most notorious of the Nazi concentration camps, a group of Jewish inmates would perform the Verdi Requiem entirely from memory before the Nazi offficers who not long after would put most of them to death. “Whatever we do here,” their young conductor told them, “is just a rehearsal for when we will play Verdi in a grand concert hall . . .”

His words could not help but echo in your reviewer’s mind as she heard and watched this “Verdi in a grand concert hall.” So, too, did those of Scott Tucker: “Kennedy is remembered for many things … but he had the bold perspective, in those stressful times, to articulate a vision of America which was ennobled by artistic achievement.” The doomed conductor of Terezin and his fellow musicians, had they been given the chance, would have felt at home here.

Running Time: One hour and 45 minutes, with no intermission.

Legacy and Life: A Musical and Visual Reflection played on November 10, 2013 at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts’ Concert Hall – 2700 F Street, NW, in Washington, DC. For future Kennedy Center events, go to their calendar of events. For future Choral Arts Society of Washington, go to their calendar of events.

https://youtu.be/OqPhKgdYWbU

This is one of the most intelligent concert reviews I have ever read, and I have been reading them for about 60 years.