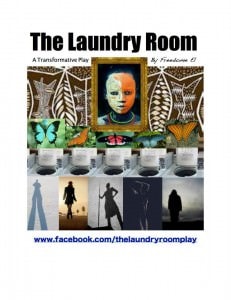

The Laundry Room debuted in the 2012 DC Black Theatre Festival and was performed again in the 2013 festival. It returned on the 2014 festival program and played to an enthusiastic audience that seemed eager to take part in the show’s passage toward healing uplift. The play was written and produced by Freedome El, who owns and operates a health-and-wellness “life transformation business,” which I mention because The Laundry Room’s aspirational commitment to improving women’s lives is palpable throughout. Freedome El also co-directed (with Kim Ayubu Bey) and plays one of the characters. With her resonant voice and skillful in-the-moment acting, Freedome El, off stage and on, stands out as a creative force.

The play begins in a public laundry room where five women come to wash and fold clothes. A program note says this is “the story of five women who embark upon a journey of transformation and healing guided and protected by an ancient spirit guide, in a place where everything comes clean.” That ancient one is Sekmet (Asantewa Lioness), who wears a bright orange ceremonial robe; introduces herself as a “guardian, guide, helper, and healer”; moves silently and dancerly through the show; and carries a staff with an ankh at the end that she now and then waves over each of the women’s heads as a kind of blessing. Meanwhile the five women have an extended conversation about men—the men in their lives and men in general.

We learn that when Yolie (El) was on a pleasure trip with a man named Suliman, he raped her. Khadijah (Maya Ayanna) is the third wife of five in a polygamous marriage. Turie (Tiffani “Cream Brown”) sells sex to pay for college. Val (Jaharri Jah) is a financially independent career woman and self-described cougar who has no need for a husband. Jo (Melanie Barnes) is a lesbian, owns the laundry, and has no need for men at all. They have plenty to talk about—and the riffs and ripostes get dishy, catty, and snarky. There’s obviously zero sisterhood going on.

A dream sequence follows after which we find the women again in the laundry room, still folding clothes and conversing, but the topic is no longer men. It’s God. Everyone has a different take on God, but now they do not contest and carp at one another; instead they forge a connection—a bond not only with one another but with the divine and their power as women. To paraphrase Nellie Forbush in South Pacific, they wash their men right outta their hair by bathing in God’s light.

As theater The Laundry Room could use a lot of work. The slow pace made the length feel overlong. Both the two extended conversations—the one about men and the one about God—went on and on randomly without clear character arcs or momentum. The silent hovering figure of Sekmet seemed distractingly irrelevant to the stage action most of the time, and bewildering when waving that wand. I could say more but I won’t. Because the truth is, The Laundry Room is only packaged as if it’s theater, as an entry point of ordinary-life familiarity, as a recognizable way in to a whole other experience altogether. It’s actually a personal and communal transformative experience grounded in women’s friendships, ancient wisdom, and spiritual healing practices. And as such it transcends words.

Running Time: 2 hours and 20 minutes, including a 10-minute intermission, but not including the post-play incantation.

The Laundry Room played one show only on June 29, 2014 at the Ira Aldridge Theatre at Howard University, 2455 6th Street NW, in Washington, DC. This year’s Black Theatre Festival has ended. The complete schedule is online.