The play, set in two small towns in Wyoming, begins with a brief prolog in which a golem named Joseph (read by Ray Ficca) is introduced. This figure from Jewish folklore will soon assume more and more prominence in the the play, and Baldessari’s script will shrewdly explain everything you might need to know to understand what’s going on (even if, like me, you came in unfamiliar with golem lore). But first Baldessari treats his audience to some broad sketch comedy.

Emmett Budrow (Jim Brady) is a redneck Christian who has carved a typo-ridden sculpture of the Ten Commandments (“Thou Shalt Not Bare False Witness”) that was recently ordered removed from public property. The mini monument is now parked in the garage of the Budrow family home where in scene one Emmett’s annoyed wife Bethel (Elizabeth Kitsos-Kang) and her friend Norma Lou, who is Jewish (Caren Anton), ridicule it, to the audience’s amusement. Among the rapid-fire laugh lines are joking references to the contrast between Christian and Jewish worldviews and mocking references to the subliterate ignorance in Emmet’s fanatic fundamentalism.

The golem comes into the story soon thereafter because Emmett has decided to sculpt one, like an anthropomorphic shrine, in the basement bedroom that once belonged to Emmet and Bethel’s daughter, Ruthanne. She died two years ago in circumstances that resulted in a tension between Emmet and Bethel that expresses itself in their bickering, which, though very funny, hints at unspoken pain and sorrow.

Early on Emmet takes his friend Toby (Stan Kang) down to show him his work in progress—still a mass of mud, as per the instructions for creating a golum that Emmett found on the Internet. Bizarrely Emmet keeps the sculpture in Ruthanne’s bed in a coffin. Toby is freaked out—and that’s before the golem begins to move and speak! The play is well on its way on its trajectory toward the tragicomic. (Through a turn of events I won’t give away, Ruthanne returns to life in Act Two read by Sherry Berg).

As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that Baldessari is juggling quirkily disparate elements that would not seem to coexist in the same play: the hick town Wyoming environment, the legalisms between civic and religious, the prejudice Emmet considers is a “War on Christianity,” the age-old anti-Semitism that originally occasioned the myth of the golem (believed to protect Jews from Christians), and the supernatural dimension of the golem itself (which mystically ushers the play theatrically into a realm of magic realism).

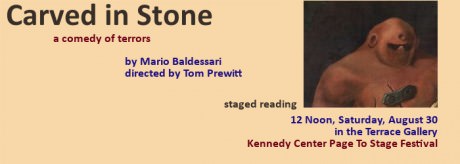

By the end, what began as Saturday Night Live sketch comedy has transformed into an episode out of Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone. Though that sounds an improbable stretch, it’s a credit to Baldessari, Prewitt, and the excellent, accomplished cast (I was told they rehearsed but once) that the audience not only bought it; they really seemed to dig it.

Emmett’s occupation is driving a truck that delivers bread. There’s a passage when trout rain down from the sky, and in the ensuing confusion the contents of Emmet’s truck spill onto the road. As the audience caught the loaves-and-fishes allusion and the image slowly dawned in their minds-eye, one could hear a gale of laughter rolling through the room.

The humor is oddball, the mystic twists are weird. But strangely Carved in Stone works like a charm.

Page-to-Stage continues through tomorrow, September 1st, at The Kennedy Center-2700 F Street, In Washington, DC. For a complete printable chronological schedule, click here.