The National Civil War Project presents the work of “a multi-city, multi-year collaboration between four universities and five performing arts organizations to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the American Civil War.” The project was inspired by Choreographer Liz Lerman, the creator of Healing Wars, which premiered last year at Arena Stage. According to Lerman, it is meant to explore “What does it (the Civil War) still mean? What is the aftermath? Where is the damage? How is it absorbed? Who does the absorbing?”

Our War, Arena Stage’s contribution, consists of twenty-five original monologues written by twenty-five contemporary American playwrights whose works have been divided into two separate evenings of performance. The playwrights cover the gamut racially and ethnically; the majority are women; the perspectives, diverse. Some of the monologues take place during the Civil War era, but most are contemporary in design. For our review of the production click here.

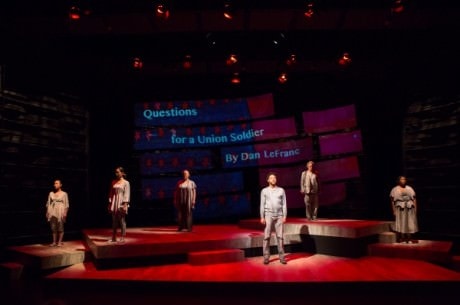

In Dan LeFranc’s monologue, Questions for a Union Soldier, a character asks:

“True or false: Abraham Lincoln’s assassination is the most significant event that’s ever occurred and probably will ever occur in the American theater.”

The question initially provokes laughter—the juxtaposition of a real world murder with the imaginary world of the theatre—how can art compete against such a reality? Then, however, the truth sinks in; one realizes just how irrelevant most contemporary American theatre—its issues and its discourse—was, is, or will be to the vast majority of Americans.

Of course, the National Civil War Project is meant to approach that void, however humbly, and fill it, however slightly. Lerman explains that the questions she asks in the project “are too big for the arts alone, or for academia alone; my interest is in collaborations that will allow new understandings.” Hence, the collaboration between major institutions.

To be sure, such goals are laudable, and who would not support any effort to infuse discourse and culture in the United States with both history and purpose. So even if Our War fails to achieve these lofty goals, it at least acknowledges the need for the arts to tackle the pressing issues of our nation and our age. Theatre should speak more deeply to the real concerns of Americans and what it means to be an American, and not just to the entertainment needs and intellectual curiosities of theatre-goers.

Fortunately, a number of the monologues in Our War rivet the viewers’ minds to the fierce and sustaining divides that fissured the country 154 years ago and that still create huge and enduring ruptures today. A few even touch on the class issues that fueled the war and to the institutional failures that the war revealed.

Because, more than anything, the Civil War represents an epic failure of American institutions to address the need for crucial change; it is perhaps ironic that this current effort to delve into that failure is being attempted by major American institutions.

In 1860, when the war broke out, it was clear that representative democracy could not solve its most cancerous social malady: slavery. What John Brown had hoped to accomplish with minimal bloodshed only a year earlier (and he was executed by Federal authorities for the attempt), needed to be accomplished through mass slaughter and destruction. And even then the emancipated slaves found themselves in little better than serf-like conditions while most of the working class men and women who had fought and survived the war awoke to an era of Robber Barons, industrial servitude, and child labor.

In Samuel D. Hunter’s The Homesteader Idahoan Gary Barton, the great-great grandson of town founder Robert Barton, has been asked by the investors and developers of a new mall to commemorate its opening. A worker at the Home Depot, Gary (played wonderfully by John Lescault by the way) stumbles along, mentioning the mall’s many national outlets, from Zales Jewelry to Old Navy, until he finally admits: “This is what he (his great-great grandfather) fought for, what they all fought for. Barton Plaza.”

Ironic laughter filled the Kogod Cradle. A war not for oil, but for shopping malls. At that moment the play reminded me of President Bush’s 2008 speech when he juxtaposed the need for more funding to fight terrorism with the need to do more shopping to help the economy recover.

Hunter’s short monologue might not have been able to make much headway into developing Lerman’s hoped for “new understandings” about the reverberations of the Civil War, but it was at least a gambit, as the economic motives that had driven the war, the corporate interests that benefited from it, and the class divides that defined it, were suddenly drawn into clear relief.

One of the most effective monologues of the evening was The Grey Rooster by Lynn Nottage (and performed with real passion by Ricardo Frederick Evans), and within it swirled all the issues of national unity, institutional myopia, class division, racial bigotry, and the mythologies, both personal and political, that attempt to bridge those real world ruptures.

In Nottage’s piece, Cato, a trusted slave on the Walker plantation in Kentucky, tells us of the death of his master’s wife, Charlotte, at the hands of a confederate Colonel. After the Walker’s two sons die in the war, Captain Walker himself goes to war, and leaves Cato in charge the plantation’s business interests, their prize-winning bourbon. They bury the whiskey and the Captain orders Cato to never tell a soul where it is.

As the war heats up, a confederate Colonel and his troops arrive at the plantation, desperate for food and liquor. He orders Charlotte, whom Cato never much cared for, as she was “born with a tongue that lash as hard and unmercifully as the cat-o-nine,” to turn over all the corn and liquor to his troops. She refuses his request, and later command, and later threat of execution, telling the hungry Colonel that the corn and whiskey belong to her.

With the noose tightening around her neck, she finally surrenders, ordering Cato to tell the Colonel where the liquor is hid. To her surprise, Cato feigns ignorance, as his master had asked him to do, saying convincingly: “I don’t know where the whiskey at, why would someone trust something that precious with a po’ nigga like me.” And Charlotte swings in the breeze.

Not surprisingly, The Grey Rooster was seemingly adapted from an interview with an ex-slave conducted by Robert J. Peterson in 1932, one of many interviews commissioned by the Federal Writers Project of the New Deal for the Library of Congress. This simple tale reveals the power of real world events, like assassinations or grey roosters, to immerse a theatre-goer into the socioeconomic and psychological power dynamics that transcend an era, even one as divisive as the Civil War.

One could easily argue that today the United States is in the throes of another epic failure of its institutions–political, economic, and social. Our immigration system is dysfunctional; our criminal justice system, deeply flawed; our economic infrastructure is collapsing, unable to produce enough jobs for the people it serves; additionally, the class divides that fractured our country 154 years ago are even worse. Plus, we have climate change hanging over our heads like an Olympian thunder cloud while our political system is so corrupted by money that it is unable to make any of the necessary corrections.

In other words, once again representative democracy must solve its most pressing social ills, and once again it seems to be unable to answer the call.

In Moo by Aditi Kapil, Private First Class Mukherjee is being interviewed by a reporter about why she joined the army. She explains it was either the army or a marriage. In other words, she wanted to become a citizen and get herself some of that American Dream. She doesn’t necessarily have a clear understanding of the situation, but even her mistaken logic is telling. She says:

And I mean back in 1860, at the start of the Civil War, the top 10% of Americans owned 50% of America’s wealth, and how did they get so rich? By not paying for labor! I mean and they fought for their zero minimum wage workforce, they fought hard for that American dream! But yo, it’s all better now, because now, in 2013, the top 10% own only 86% of America’s wealth!

You see, she’s certain that with her talent for singing she will make it into the top 10% since that’s where all the money is … the arts. All she has to do now is survive her tour and the dream is hers.

I’ll leave it to others to decide if our cultural institutions are up to the challenge of the age.

Running Time: Approximately 1 hour 45 minutes, with no intermission.

Our War plays through November 9, 2014 at Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater-1101 Sixth Street, SW, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 488-3300, or purchase them online.