When I think of Hip-Hop my imagination immediately flies to urban America, to a gritty, “tougher than leather” New York City filled with N.W.A, LL Cool J, and of course Public Enemy (#1).

When I think of Rap, I think of Hip-Hop as well, but also consider something much older, perhaps even as old as the West African griot or poet storyteller.

To be sure, the iconographies of “gangstas” and “bitches” also rear their heads, as I remember endless social commentary about the violence and misogyny within certain Hip-Hop song lyrics.

Rarely, however, do I think of middle America, of split-level suburbanites living the “dream” (1950’s style), or of the homes of fairly well-to-do African Americans who have rejected such music as so much “ghetto.” Having left that “ghetto” behind, they have taken their well paying job to “The Hill” where the rewards have nothing to do with the scratches and beats of Rap.

Idris Goodwin’s How We Got On takes its audience into that cookie-cutter terrain, that terrain more haunted by its lack of identifying features than by its want of social uplift and the “good life.” It is a terrain where, in 1988, the young African American teenager might feel uprooted and estranged even if economically advantaged.

For our review of How We Got On, click here.

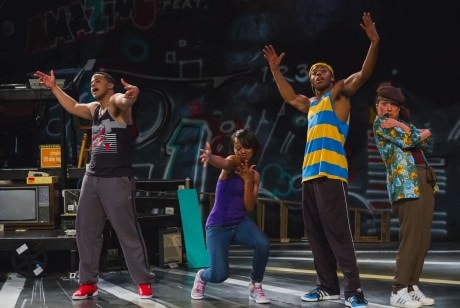

In Goodwin’s spoken-word play with Hip-Hop music, three African American teenagers, two boys and a girl, all aged 15, are living in an upscale suburbia called The Hill. A Selector, i.e., a D.J., raps their coming of age tale to an audience encouraged to clap like a concert crowd on MTV.

These three teens want more than anything to transform their poetic, performing arts souls–rootless in their parents’ affluence–from alienated and socially isolated to masters of their teen universe. In other words, they want to be remembered for their rhymes and beloved by teeming teens throughout their cul-de-sacs.

Their challenge is monumental: how to take a Hip-Hop rooted in an oppressed, urban, people of color cultural experience and redefine it in suburban terms. Not only have all the degrading economic factors been eliminated from their source experience but the communal, cultural milieu that feeds and inspires such driven reverberations is nowhere to be found.

These teens are alone in their universe, the cultural other among their white peers and an oddity among their 1988 “moving on up” black cohort. In other words, they are practitioners of a musical form best left behind in the name of progress.

Although the obstacles are great, these three teens possess an overwhelming ambition. If they can find the formula that will create a suburban Hip-Hop not only will they “get known” throughout their teenage universe but, in the process, construct new magnetic identities in the uniform soil of The Hill, a loam most resistant to anything resembling an attractive, dynamic self.

Goodwin uses the neighborhood water tower as the symbol of this suburban challenge. In suburbia, the water tower becomes the shrine where poetic inspiration might be found and transcendence experienced: if only one is brave enough to climb its towering pedestal.

The three teens journey to that tower on various occasions where each, individually, “gets on.” There they struggle to overcome issues of doubt and parental disapproval.

Meanwhile, the Hip-Hop tune grooving Selector as griot leads us and, in a way, them through that landscape of distrustful parents, who want their children to better themselves (economically of course) even as they acknowledge that a person’s roots need something more than a suburban soil to grow.

Then, as each teen discovers his flow (in this case, flow is his or her ability to let the words come without editorial interference), the play’s action reveals the true significance of community, however small and different one’s community might be. For these displaced poetic souls build amongst themselves their own subculture, a collective of three in quest of that rare art called suburban Hip-Hop.

This challenge is not unlike those found in artists everywhere and at every time. Art at its most dynamic essence is most often birthed from struggle, which comes from one form or another of social oppression or isolation. The art of itinerant theatre troupes like Commedia del-Arte or penniless painters like Vincent Van Gogh and impoverished writers like Edgar Allan Poe and dead-broke musicians like any number of Mississippi Delta Blues musicians, from Howlin’ Wolf to Muddy Waters reflects that struggle. Hip-Hop is no different. At its origin the struggle shines through.

After the art is born, of course, and made financially viable, it is then practiced and experienced by those with the time and money to enjoy such luxuries. And the starving artist works on.

How We Got On focuses our attention on the artistic journey not as pathway to success but as pathway to survival. In today’s cultural environment, where concepts like the “creative economy” tend to make art all about the buying and the selling, the stimulation of nearby restaurants and new construction projects all geared to rejuvenate a once dying urban environment, it’s great to experience a play where art returns to its own roots.

How We Got On is not about how these kids found fame and fortune writing music and lyrics–I’m personally up to my gag-reflex in such Hollywood nonsense. In How We Got On the artistic process is on display, and in that window we see how art really saves lives, for it gives young people–in fact, all people–an opportunity to express themselves to others. The issues these teens are dealing with aren’t about life and death, but they are about joy and creativity and whether or not those two vital ingredients will remain an aspect of their lives or no.

And that is just one reason why this coming of age tale bubbles with enthusiasm and kinesthetic energy.

The other reason lies in the very nature of the art. Hip-Hop is an oral form. Although rhymes can be devised sitting at a desk, the real “flow” comes when the artist stands before the crowd and in the heat of the moment creates. The words might reflect trials and tribulations but joy is the overriding essence of the work.

In that too, Hip-Hop is no different than all art. It must be born in the moment,for in that moment of creation its essence emerges, indescribable in its verve, but full in its detail, guiding both the art form and our reception of it.

And more than anything else, that’s what How We Got On is about: the flow of creation and the joy that emerges from it.

A truly unique theatrical experience in so many ways.

Running Time: 1 hour and 20 minutes, with no intermission.

How We Got On plays though November 22, 2014 at Forum Theatre in residence at The Silver Spring Black Box – 8641 Colesville Road in Silver Spring, MD. For tickets, purchase them online. Additional Pay-What-You-Can tickets will be available at the box office one hour prior to every performance.