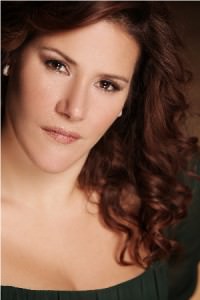

Rising local soprano Danielle Talamantes talks about the Met, concert music, and the opera singer’s life

Politicians and lobbyists running to catch the Acela at Union Station in D.C. or Penn Station in New York have nothing on Danielle Talamantes. On Saturday, November 1st she was so much in demand that making both of her obligations – at the Metropolitan Opera in the afternoon and singing Mozart’s Requiem and a Mozart solo cantata with the National Philharmonic at Strathmore that evening – had only one transportation solution: a helicopter ride from Manhattan to Montgomery County.

Now Danielle, a native of Vienna, Virginia and a 1998 Virginia Tech grad, is prepping for two career milestones – her first featured role at the Met in February, and the public release of her first CD this Sunday evening at Vienna Presbyterian Church, right where the album was recorded.

Yet for all this, Danielle holds fast to certain principles that she imparts to her own vocal students. Those include the importance of concert music presented by classical vocalists in intimate venues, side by side with splashy operas; a realistic evaluation of one’s voice and maintaining knowledge of it as it grows and changes; and direct audience connection rather than holding opera “stars” at a distance. Earlier this week I caught up with Danielle at Caffe Amouri in Vienna, where she still lives and teaches. Here are excerpts of our conversation:

David: Let’s start by looking forward and then we’ll go back to your helicopter adventure. You have some very interesting stuff coming up. You’re going to be at the Met with Carmen in February but once again, as soon as you open you’re going to be back here to be at Strathmore for one evening.

Danielle: And actually right before I go the Met I’ll be in Cedar Rapids, Iowa doing Don Giovanni, and when that wraps up I have less than a week before my contract starts at the Met, where rehearsals for Carmen start at the end of January. It’s tricky. I’ve had a couple of occasions specifically with the National Philharmonic and Strathmore where I’ve been booked before the Met contracted me, so that I’m sort of trying to be really creative with how I get to places. So opening night of Carmen is Friday, February 6th at the Met and I have to get permission from the Met to be released – anytime I’m under contract there if leave the immediate area I need permission. So then I have go down for a rehearsal for the 10th anniversary gala of Strathmore. The big celebration is on the 8th and then second performance of Carmen is on the 9th.

And on February 8th you are singing the soprano solo in Beethoven’s Ninth.

Yes.

And then you need to be back in New York to do the second performance of Carmen the next night, is that correct?

That’s correct. Actually the Met’s requiring me to be back in the city by midnight on the 8th.

Let’s not assume something. Tell people how an opera at the Met works. You’re not performing night after night. At the Met you perform what, every 3 or 4 days?

Generally yeah, but I mean, interestingly enough, in the rehearsal process sometimes it is day after day that you are performing the entire show. You’ll typically get two days off between the final dress rehearsal and opening night but then, yeah, one to two performances a week, generally.

And you are doing the full run of Carmen but not everybody is, if I’m not mistaken some roles are shared, is that correct?

Sort of. Carmen actually just wrapped at the Met, they had a run of eight shows with a completely different cast. And so when the show goes up in February it’s a whole new cast.

And you’re playing the role of Frasquita. Tell me something about the role.

It’s a really fun role. So Carmen’s got these two kind of sexy, gypsy sidekicks and they’re largely supportive roles, neither Mercedes nor Frasquita has any arias per se, but we’re on stage a lot, pretty much any time Carmen is.

But you do have a trio with Carmen?

Yes, in the third act, it’s in kind of the gypsy mountain lair. It’s kind of a turning point in the opera where we’re reading tarot cards and they’re not turning up well for Carmen (laughing).

Between Frasquita and Mercedes, your character is the more optimistic one?

Well you know it’s interesting, in that particular scene the two girls are kind of involved in their own card readings. And Mercedes talks about falling madly in love with this gallant soldier and he, you know, holds her up on her horse and they ride off into the sunset sort of thing. And my cards read that I marry a very wealthy old man who then not so unfortunately dies, leaving me an heiress. So I mean optimistic (laughing), in terms of a luxurious life, I suppose, yeah.

But if I’m reading your schedule right, you just rehearse this for one week leading up to opening night? So as opera practitioners you are not sort of walking in one day and not knowing your role and you start learning it, rather you are expected to show up prepared, is that correct?

Oh yes, the contract says note-perfect and off book, so totally memorized and ready to go. This particular cast, everyone singing in this production that goes up in February has done this production before, not necessarily this season. In my case I did “do” it this season because I was covering, understudying Frasquita in the fall, so I was involved in those rehearsals and the girl that I was covering was very healthy, she never got sick, so I never went on. But she’s actually covering me when the show goes up in February.

How interesting.

They don’t always do that. But the rehearsal period for this second run of the show this season is much shorter than what we just had, so everybody needs to have done it before. It’s going to be like review, nobody’s learning anything in terms of blocking and staging.

So speaking of this schedule, clearly you have a relationship with the National Philharmonic, which to be clear is not the National Symphony Orchestra, it’s one of the orchestras in residence at Strathmore – the other one being the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra – and you did have an interesting adventure on the day of November 1st where you managed to be at both the Met and Strathmore on the same day. Tell us what happened.

Well Peter [Piotr] Gajewski [the music director and conductor] at the National Phil, he’s really on the ball, he’s booking contracts out well in advance. I didn’t find out about Carmen until after I was already booked with the National Phil. So I had to cover at the Met on November 1 the final performance of [the first run this season of] Carmen, it was the one that was the HD cinema broadcast, so I had to cover from inside the house of the Met. One o’clock show, I couldn’t leave until my character literally walked off the stage for the last time, which was about 4:30.

That’s a contractual rule?

Yes, even if she’s totally, totally healthy, nothing’s going to go wrong, something could happen.

And it presumes that something could happen, and then suddenly you’re on, and you’re a different person in the same role?

Right, but you know, it would be somebody in the same costume … So the concert at Strathmore was 8 o’clock and I was the second thing on the bill, there was just a short choral piece of four minutes that started the concert, and then it was my solo cantata Exsultate jubilate. So I needed to be at Strathmore at 7:45 at the absolute latest. No Acela trains, no air shuttles worked, so Peter was very creative and decided to pursue alternative options to get me there in a timely fashion. So he found a helicopter company based out of Laurel and it was a lot of back and forth and I ended up paying for it. Which was fine, I really wanted to do this, I have a great relationship with them and it sounded like an adventure to me.

Is that like chartering a plane? That sounds expensive.

Very expensive. My fee was basically a wash. But I would do it again in a heartbeat.

So where exactly did you go to board the helicopter and where did you land?

Well my husband was with me, we bolted out the backstage door of the Met at 4:30 pm, caught a cab and went to the 30th Street Heliport, which is at 30th and West End, so like 12th Avenue. It was raining, in fact the whole thing almost didn’t happen. The helicopter pilot was saying there’s this weather system sitting over Manhattan it’s probably not going to happen. But at 1 o’clock we got the greet light. Our helicopter picked us up at 5:15 – and it was a little bumpy getting out of there! – but then it was pretty smooth sailing all the way. It was so windy that day, the pilot keep reassuring us that helicopters like wind. In fact, the tailwinds were so strong that instead of 2 hours it only took 90 minutes to get from midtown Manhattan to landing on the grounds at Strathmore which we had FAA permission to do. The original Strathmore mansion is on a kind of a big open field, so that’s where we landed and then we just walked in the door!

Did you have time to get dressed and everything?

Oh yeah, in fact I beat all the other soloists there. I got there at 6:45, the concert was at 8 so plenty of time.

Well, one of the things about recitalists and in opera, I mean obviously there must have been somebody else who could have gone on for you if absolutely necessary.

Yeah.

So really, performers like yourself, you’re carrying around a lot of inventory in your head, is that right?

That’s a good way to put it.

Musical theater actors do in a different sense, but they have to rehearse it. But to some extent you’re called upon to be possibly jumping into things a lot.

Uh-huh.

That reminds me less of theater actors but rather of the way that classical pianists and violinists, if you look at their repertoire, it’s quite large. Is there some plasticity of your mind that goes to that? Is it just the culture of opera, once it’s in there is it like riding a bicycle? How would you put it?

It’s compartmentalization, you know, recall is a huge part of this business especially when it’s a last-minute, “we know you’ve done the role, we need you right now” kind of thing. For example, so I just finished [understudying] the Carmen production at the Met and I sang in rehearsals, so even though I didn’t sing on the stage I know that in a very short time I’m going to need it. So I will listen to that or practice it every couple of weeks, just to keep it right there so that it’s not effortful to recall it. Right now I’ve got recital repertoire, Frasquita’s in my head, I’m learning [the role of] Donna Anna for Don Giovanni. I find that everybody memorizes differently, but when I get into a zone of memorizing my brain is very efficient, like it just knows where to put it, how to store it, how to recall it. And when I get out of that zone, it takes a while to get back in. But [what helps is] it’s good to just always be learning something new.

Tell me about the logistics of the Met. If I look at their schedule this week, they have four entirely different productions running on the same stage, which is different than most people’s experience of their groups negotiating for a block of time in a facility, they “own” the theater, they leave, they strike, somebody else comes in. How the heck does that work?

It’s a huge, huge company and there are some 16 unions involved working at the Met. So you mentioned there are some four productions that going on in any given week. Well you can almost double that because what your average visitor doesn’t realize is that there are also shows in rehearsal during the day, shows that haven’t gone up yet. So you’ll have a 10:30 staging rehearsal on the main stage that wraps at 1:30 or 2, they strike that set, they bring out whatever’s coming on for the evening. I mean there are amazing angels who work in that house to make it all happen from scheduling rehearsals and all the spaces being utilized at exactly the right time.

But do you have a sense, does the light board just get reset every single time, and certain physical things about the tech? I think most people around here that I know in theater, that would give them a heart attack that somebody messed with their stuff during the day.

It’s the same group, I mean it’s the same [overall] stage crew who is every day handling this equipment, they’re not all on the same show but everybody’s got their job and their place. It’s a tightly run ship!

What about yourself as a performer? When you arrive there do you arrive at the same dressing station, the makeup station that someone else used the night before?

Yeah, actually someone was probably in there that afternoon doing a dress rehearsal or something. But all the rooms are comfy, well-lit and there’s a piano, there’s usually a couch, and it’s certainly cleaned in between. And your makeup and wig people and dressers come to you. So there’s not a lot of confusion out in the hall because everybody is kind of assigned to their place and it all gets done.

Opera is part of, and I mean this in the broadest sense, classical music, and other practitioners in classical music, you know, violinists and pianists and others, if they haven’t started on their instrument by age 6 or 7 or 8 they probably won’t have a chance. How does that work for opera singers? I mean this both in the sense of people reading this for themselves but also parents who see the tremendous interest in this area, sending kids to musical theater camps and all that kind of stuff.

I can answer that in two ways, one from my own personal experience and two, as a private voice instructor, so I’m teaching those kids, I talk to those parents. For me and I’d say especially for someone who is considering singing as a career path, when I was starting out, it should be on the piano, or maybe the violin. Some instrument to get the basic techniques of reading, theory, that sort of thing. The vocal cords are so small, the length of your thumbnail, that’s it. So pre-puberty, it’s not a good idea to have private voice lessons. Choral singing certainly is fine, but the individual intensity of a voice lesson is just not meant for children.

So I took piano lessons. My mother, who is an organist, refused to teach my younger sister and I but she insisted that we have piano lessons, which we hated, but I am eternally grateful for them now. So I took six years. I tried violin, I wasn’t very good, I played French horn, I wasn’t very good.

Well it’s hard to play the French horn!

It is, it is! It was a big instrument. So all the while singing in choirs in church and school. I really can’t remember a time when I couldn’t read music, so that’s been a fabulous gift, I mean it was something I learned but I really don’t remember learning it. It was probably middle school when I started getting into district choruses and being chosen for solos and that sort of thing. And I started taking lessons in eighth grade, which is a great age because your body is sort of strong enough to handle that intense vocal work. You know somewhere between 12 and 14, depending on each individual. I studied through high school, sang in madrigals, sang in the adult church choir, at Vienna Presbyterian Church.

I loved music but I just didn’t know, do I really want to pursue this as a career, can I make a living doing this? I was actually looking at doing archeology for undergrad, but every school I went to visit I went to the music department first to see what kind of choir I could join so I could keep that musical hobby alive, and then I realized this is ridiculous, I should just major in music and see what happens. So after being accepted to a couple of conservatories with scholarships, I made the decision to attend Virginia Tech because I wanted a college experience. I was young, I was barely 17, and I had a feeling that the conservatory-like environment would send me screaming and running away from music.

I think we all know a couple of stories like that.

So as it turns out it was perfect. It was a nurturing environment, a small environment in the [Virginia Tech] music department and I was suddenly the big fish in a small pond which I had never been before, especially in this area of Northern Virginia. And I doubled-majored in vocal performance and music education and I was thriving in that environment and having a great time and started to see, yes, I do want to pursue this. I knew I wanted to get my masters and continue to study. For vocalists, I mean I would say for whatever genre you’re singing, women don’t reach their peak until the mid to late thirties, men sometimes a full 10 years later, so I mean there’s the incubation stage and then it just kind of keeps going, even post-graduate I found myself back in this area because I knew I still had growing to do.

So there’s all these different stages. I went to Westminster Choir College for my graduate work, and that was the exact type of environment I knew I wasn’t ready for in undergrad but I was totally ready for as a grad student. Westminster is known as “the college across the street” from Princeton, although it’s actually affiliated with Rider University. It’s a beautiful school, very small, I mean I went from a campus of some 20,000 kids to a campus of 300, both undergrad and grad.

You were always thinking of the opera world? You were never particularly thinking of musical theater, is that right?

That’s accurate. I didn’t think I was very good at musical theater, or any other genres. But when you say “opera,” I mean, people ask what I do, and it’s easiest just to say I’m an opera singer, people know what that is. Because if I said I’m a “classical vocalist,” that’s confusing.

But that’s what you think of yourself as.

Yes! I’m a recitalist, I do sing opera, but I concertize with symphonies, I do chamber music, it’s kind of a big umbrella.

You know that body mikes are now very common in musical theater. Maybe as a result, sometimes actors may not realize that the human voice itself is a musical instrument. They’ve always sung but they don’t realize that there is a resonance inside their body that functions like the space inside a violin. Am I right that it’s that kind of revelation that you need to have to realize that you have your own ability to generate a louder sound? Or is it something else, a logical leap that people need to make if they want to try this kind of singing without the equipment that is now getting to be almost universal in musical theater?

Well I mean back in the day, Rodgers and Hammerstein, nobody used mikes. That technology really wasn’t available and if it was it was crappy. That being said, spaces that are being used for musical theater or even opera are getting bigger and bigger, so there’s a problem, unless they’re designed acoustically to support, you know, acoustic performance. I mean, I never had that revelation because that was the training that I received. And in my studio I blend classical repertoire with musical theater and I tend to really lean toward the traditional Oklahoma! and West Side Story, I don’t know a lot of the contemporary Broadway stuff, and I find the technique is completely different than it was from the 40s, 50s and 60s. But you know even Sondheim [as opposed to some other contemporary composers] was still in the tradition of a legit technique as you sing.

Well certainly, he goes back to the late 50s.

Yes! But I mean, ask a dancer that. Their whole body is their instrument. So for a singer not to realize that their body is their instrument, that’s so foreign to me. You know, I mean if we get sick our instrument is sick. If we abuse our instrument, we can’t work. We are what we eat, we are what we do. It’s through the knowledge of possessing the ability to fill a space without amplification, I mean we’ve all cheered on friends on at a sporting event, you can make some noise! If anyone stopped to think about it, they’d realize it’s very, very possible.

Is there any one specific thing that you see people do wrong that they need to fix?

Whether it’s classical singing or musical theater, whether it’s with amplification or not, I see time and time again singers not supporting their sound with air flow, they’re doing it solely with their muscles and as we mentioned, the vocal cords can only support so much pressure. If it’s not a combined effort of breath sort of supporting your vocal folds to do their thing, then forget it, it’s going to short-circuit in a really short time.

Do you start your students with breathing exercises?

That’s part of it. I have large series of vocalizing exercises that are designed to strengthen one part of the technique or another. I use the old-school methods from an Italian bel canto approach, starting with beginning repertoire and implementing all these techniques and off they go.

With regards to breathing, that idea that when we inhale that everything kind of sucks in, it’s insane. We literally are like vacuum cleaner bags, you turn the vacuum on and it fills up with air, you have to make room for all that oxygen, that expansion, there’s definitely nothing that’s contracting when that happens.

Tell me about your career. You started singing with orchestras before you started getting roles?

Well, fast-forwarding to the last two years when I really hit my stride in terms of size of the voice, weight, that sort of thing, back when I finishing undergrad and grad work, my voice was much smaller, it was still my voice but it was smaller, maybe thinner, certainly clear and bright and all that kind of stuff, but much more suited for chamber music. So I did recital work, you know with piano or just a couple of instruments, and then it started growing enough that it made sense to sing with orchestras, some early Handel and Mozart, nothing too big. When I relocated back to Northern Virginia after my grad work, I mean this place per square mile has the most orchestras and oratorio societies than anywhere in the country, it’s crazy.

Orchestras, choruses, theaters, it’s unbelievable.

It’s fabulous too for people who maybe have been trained and that’s still a huge passion of theirs but not in their day job. There’s plenty of opportunities to feed the soul. So I started concertizing quite a bit in the area, and sort of generating my own recitals. When you see well-known opera singers do recitals at The Kennedy Center, at Lincoln Center, that part of the career usually doesn’t happen until after the opera success. But I find that there’s a great deal of growth that can happen in the recital process preparing all these individual art songs, you know, just poetry set to music by any myriad of composers out there, I mean Schubert wrote over 600, just this one man. So I was growing and working with a very trusted teacher in this area [Elizabeth Daniels in Silver Spring], making my way, started auditioning for regional opera companies, and summer apprenticeship programs.

And then in my mid to late 20s I started on the competition circuit, which is another sort of branch between academia and hitting it big-time. Because these competitions, while you may win them and maybe win accolades and money, more importantly you’re singing for conductors, stage directors, artistic administrators, the people who are out there hiring during the regular season. So I had a very successful couple of years as I was about to “age out” of a lot of these competitions which usually cut off somewhere between 30 to 35.

And that’s when I sang for Lenore Rosenberg who is the artistic administrator at the Met. I did not win this competition but I made it to the finals. In fact there were two different competitions where she was my judge in the finals. And that resulted in a phone call from someone at the Met saying we’d like for you to come in and audition. I thought it was a prank, the Met is calling me? So I went in and sang again for Lenore again at the Met, I will never forget that day, it was just a huge honor to have that opportunity. I never set the Met on my list of hopes because it’s the pinnacle not just in the country but in the world. Not even two weeks later I was offered a contract so that started my relationship.

You’ve had some interesting observations you’ve shared with me when I’ve asked you what your voice type is, and you kind of give me a “that depends” kind of answer. How do you characterize yourself now? And tell me a little bit about what you project into the future, why that’s important for people to think about.

As the voice is our bodies which are constantly changing and especially if you’re continuing to study which I am – I will always study with someone – the voice is always changing, so I came from being from being a light coloratura which is sort of a high, spinny voice, certainly not the Queen of the Night [an ultra-high part from Mozart’s The Magic Flute] but the “ina” roles [referring to the many female characters in opera whose names end in “ina”], the young ingénue characters, and now the voice has grown and it’s settled a little lower so I don’t have all those stratospherically high notes any more.

Okay, people want to know, what is your actual range?

In the Mozart I just sang a couple weeks ago he asks for a low A below middle C to be sung – you know, to be sung over the orchestra – and I’m very comfortable singing high Cs. The C-sharp is fine, I do the Carmina Burana quite a bit, there’s a D in there, and that’s a stretch, I don’t live up there. So currently I declare myself as a lyric soprano. For example we were talking about Carmen, if you talk about two soprano roles, I would generally consider myself more like Micaela more than a Frasquita. That’s a little more lyric, a little fuller, Frasquita is kind of soaring over the top of everything, it tends to be a lighter voice. But at the Met you have to consider the size of the house. So maybe my voice quite isn’t quite big enough to sing Micaela, so they have me singing Frasquita. The Donna Anna that I am singing in Don Giovanni in Cedar Rapids – that is a sizable role, it’s a very meaty role. But more likely the Met would cast me [in Don Giovanni] as Zerlina, something that’s a little lighter, just based on the size of the house.

Can you project, as you go into your forties, do you expect your voice to change?

We’ll see, I mean I think if it does anything it might darken, maybe fatten up in the middle so that I might start flirting with some of the more Verdian roles. It has a potential to get bigger. Certainly never towards Wagnerian. That’s not in my future.

Let’s talk about languages. Obviously you have sung in Italian and German and French.

Yes.

And Spanish. And what about English?

Oh yes, most people don’t stop to think how difficult English is, especially to sing it. And I’ve sung in Korean, I’ve sung in Japanese, I’ve sung in Russian.

So when you’re preparing for a role, the words that you are singing in a language, is it a question of, at one extreme, you could have a conversation in that language? Or at the other extreme, it’s just abracadabra and you’re just learning the syllables phonetically?

If it’s a language that I’ve had training in, that is to say Italian, French, German and Spanish, phonetically I can read but I just have a natural affinity from hearing it, so now from looking at it on the page, I know how to pronounce it. But then it’s a combination of me doing word-for-word translations as well as looking at translations of the libretto and literally writing it in, writing in the score.

But I’ll be honest with you, there are only so many subjects in most operas that are performed, so you really start to pick up the language after a while (laughs). Even if I wouldn’t venture to start speaking in Italian, I can read a line and I know what it says, all those words I come across frequently. You only sing so many Latin masses, and you’re like, oh yeah, I know what the translation is. But the Met does provide language coaches, they’re always in rehearsals. And then in addition to singers studying with a technicians, they need to find coaches, repetiteurs [a form of rehearsal pianist in opera], drama coaches, people who you trust who can be brutally honest with you about how this should be pronounced.

And then also, trends shift. So there was this trend in French where it was considered gauche to sing a guttural “r” in a phrase like très bien so for a long time, it’s been, you just flip the “r.”

I didn’t know that. How interesting.

But now it’s coming back into fashion to put [the guttural sound] back in there.

I’m going to make a huge generalization and you take it wherever it goes. Sometimes theater people go to opera and they love the music but they have comments about other things – the staging, the acting, the chorus singing, the fight choreography, one or another thing they’ll say you know, I didn’t think that was as good as it could be. What one or two things have you seen change for the better in your time in opera that people identified as a possible weakness, including at the Met? Or you may reject the premise of the question.

Oh no, it’s a valid question. You know, because we’re not amplified, there are some limitations. We’re being required to pump out sound over an entire orchestra, so if the staging gets really complicated the music will suffer, and ultimately that cannot happen. That being said, in this production of Carmen, one of the opening scenes in Act 2, Carmen steps over a guy’s head and steps on a table and then falls back and she’s singing as guys [are catching her]. So we’re trying! And then if you’re talking about the depth of the stage, sometimes we can’t use the whole stage unless there are people in the back who are not singing because they simply wouldn’t be heard.

The Met has taken some chances. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. You know, the HD cinema, that was kind of a big leap trying to bring it to the masses. They’re constantly adding new [movie] theaters but there’s been a ripple effect because now all of a sudden we’re being looked at under a very large microscope, the Met is spending more money on costumes, sets, makeup, all of those things so it looks like the movies. Opera is a spectacle, it’s meant to be seen as a whole picture, it’s an interesting venture but I think it doesn’t quite have the integrity of what opera was designed to be in mind.

Of course then the Washington National Opera has done the Opera in the Outfield at Nats Stadium and a couple of other larger companies are doing that sort of thing, and people come out for it! So for whatever needs to be perfected, fine, the powers that be will work on it, but if people are coming, they’ll find a way to make it work.

After we’re done talking today, you have a rehearsal for something very interesting this weekend, even though I think the album has already been released.

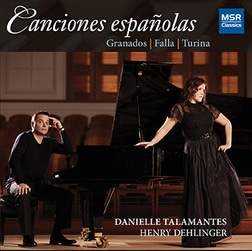

Yes, this is my debut album, it’s called Canciones españolas and it’s an album of all Spanish song featuring three composers from Spain. The album was technically released on August 6th but the process has been a little long. It’s on the MSR Classics label and this Sunday is our official CD release concert and reception. It’s kind of a big thank-you to all of our fans and supporters. The album was made possible through a Kickstarter campaign that my pianist Henry Dehlinger and I did. It’s really exciting, I think the album turned out very, very well. It was actually recorded in the very space where the concert will take place, which is Vienna Presbyterian Church. The concert will feature not the entire album but selections from it. I mean there are so many recordings out there of wonderful lieder, French chanson, Russian music, but there’s a vast wealth of Spanish repertoire that people don’t know even about. This is gorgeous, sensual music and a lot of these composers studied in Europe, in Paris.

Tell me about some of the songs.

The Falla [composer Manuel de Falla] that we recorded is probably one of the most well-known cycles of Spanish song. It’s “Siete Canciones Populares,” seven folk songs essentially, they’re fascinating, there’s a lot of kind of Moorish overtones, this Arabic scale actually that you hear a lot. The text I would say is what the folk part is, but certainly the accompaniment and the melody is very sophisticated. The Turina [composer Joaquín Turina] is just “Tres Arias,” they were both new to Henry to myself, they’re epic, they’re huge journeys, the first two are over 6 minutes long.

Is it on Amazon right now?

It’s on Amazon, CDBaby, Archive, if it’s not on iTunes yet it will be shortly.

A very important part of today’s work as an artist are websites and all of the marketing that you’re talking about. Tell me how much time you spend on marketing, on your website and so on.

That’s a wonderful question. I update and manage my own website, right before I came here I threw up a post on Facebook sharing the event, I’m sure everybody is excited for Sunday to come and go (laughing) because I’ve really been pushing this event. I don’t know about a full-time job but every day I do something. I make a phone call, I send an email, social media, anything because our attention span is so short. And for a concert like this it’s free when I have friends who are coming to see me at the Met and they’re paying outrageous prices for a single ticket, not to mention staying in New York and getting there. This concert with this beautiful music is free, so people should know about it, should come out.

Where do you find the balance? I see some young classical artists’ attempt at a hip marketing image. Some of it is genuine and some of it is a bit of a put-on. What kind of image do think is important to be putting out there?

Certainly you want something alluring that will catch people’s eye. I love to use intrigue. I mean, the cover of my album, my pianist is in that picture, the record company was saying it really should be you on the cover, but I said absolutely not. This is a collaborative album, this is a duet. Everything we’ve done with this album we’ve done together. And I love the picture we chose, people are saying to me, what were you guys talking about, I’m looking away from him I’m not even looking at the camera and he is.

So the pianist steals the focus? I like it.

Well we’ll see about that! But when I’m singing in recital, I want people to go to their translations, asking, “What is she singing about?” and making them think. The latest sort of photo shoot headshot thing that I did coinciding with the album, I was kind of going for that Spanish sensual flair, that’s sort of what’s permeating all my graphics stuff that’s out there right now.

And the financial insecurity, the variability of all this. At some point you have to accept that and not worry about it, or you must worry about it?

I think finally now, universities are getting on board and offering classes, music industry, music business, I mean I got kicked out the door at Westminster and out you go, how do I do my taxes, what do I write off, I didn’t know any of that. For any musicians I know it’s a patchwork career, and it’s a balance of maybe supporting your music needs and maybe eventually it will shift so that it’s your primary income. For me I had an admin job for seven years but then I started building my voice studio and eventually I was making enough with that plus gigging. And now I’m having enough success performing that I’m having to really pare down my studio, I’ll always be teaching, it’s just a question of how much.

We should make clear that just because you’re at the Met doesn’t mean you have some sort of salary with them.

Oh I do not. I’m a member of AGMA, which is the American Guild of Musical Artists. I have to be a member with AGMA to work at the Met. There are different categories of performers. I’m a “Principal Artist” and my contract is as a per-performance artist. So I am not salaried, I don’t get health benefits, it’s contract work. There are artists, wonderful colleagues of mine at the Met, who are Plan Artists or Weekly Artists, and that is salaried, they do get health benefits. I prefer, I’m happy with what I am. For years I’ve been supporting myself, paying my own health insurance, making it work. Without a doubt I know that this is what I’m supposed to be doing. I have gotten tired in the past and I’ve had friends saying you know, just keep going. So many people who got the role and I didn’t in my early twenties, they’re no longer in the business anymore, and I am and I’m not going to stop.

Tell me about the role of an agent in classical music and opera.

They’re well connected, and they open doors that I can’t. I mean for years I did not have management and boy, you want to talk about a full-time job. When I didn’t have an agent I literally was contacting opera companies saying I’m in between [engagements] right now I’d love the opportunity to sing for you and sometimes I would get auditions and sometimes I’d get no response whatsoever. So they’re well connected and they get the press releases from opera companies when they come to town to hear singers in New York.

I think it’s fascinating to tell folks, you just had an audition for the Virginia Opera, and for that you had to go where?

(laughing) Yes, I went to New York to audition for Virginia Opera. This is officially, late fall is considered audition season. So these companies are coming from all over the country, like Hawaii, Alaska, you know, they’re coming to New York City to hear singers. First dibs go to managed singers, usually, and then some companies will consider hearing unmanaged singers. So I was in that lot for a long time and that was a good fight (laughs).

Opera, where does it stand in society? Is it really stratified where you’re either an opera person or you’re not? Is it broadening out? Where is it in general and what does the world of opera need to do to continue a good path?

People that I talk to who grew up in an environment where classical music was encouraged, those are the ones who are sort of a built-in audience. I’ve talked to a lot of people who say I’ve never seen opera or I don’t like opera and I always say “What kind of opera don’t you like?” There’s a lot of different kinds of opera. Certainly in a way this whole HD thing, sure I’ll spend 20 bucks, I’m not going to spend 200, I’m going to spend 20 bucks to check it out. And there’s this sort of movement now of house concerts and chamber music in bars, you know where people don’t necessarily want to commit an entire evening to sitting in an uncomfortable suit and not moving and sort of being a stone for two hours, and so these bars are designating an evening for chamber music and people are coming out for this, and anything to expose people to the music. I think that’s what will open their minds to wanting to go see more kinds of classical concerts, recitals and opera.

I think on a big picture maybe opera kind of makes the classical music world go round, but wow, it’s just the tip of the iceberg. And if chamber music or recital music is a little more accessible or intimate. Henry and I are hosting house concerts, that was one of the rewards for Kickstarter, so we have people paid to purchase whatever and we come and do a house concert for them. And it’s so intimate, you know, you get to talk to the artists and sip on your wine and ask questions.

I think it’s worth noting that if you’re in New York it is possible to go to the Met for about 35 dollars.

Oh yeah and the rush tickets. Between Family Circle which is the highest balcony level – acoustically there is not a bad ticket in that house – you know, bring your binoculars, it’s fine. But they also have their rush tickets where you can get a ticket for 20 or 25 dollars if you’re willing to go two hours early.

You made mention of sitting in uncomfortable clothes. On a Monday night when I was there it was neat to see some young folks all decked out, but I saw plenty of people who looked like they were going to the drugstore or a ballgame. At the Metropolitan Opera! I don’t know how you feel about that but I just think people need to know that.

It is interesting, so what do we say, like, don’t come? No, please, come! Gosh, if jeans are all you brought, okay! You know, there’s no dress code. But you know, butts in seats, like, that’s what needs to happen.

Any particular role that you’ve done that has really touched your heart?

Both Violetta and Mimi I’ve done. La Bohème, it was a concert performance down in D.C. with the Capital City Symphony, actually Victoria Gau is the assistant conductor with the National Phil, that’s her symphony.

And La Traviata, where did you do that?

I did that in Fremont, California, so both of these places were wonderful places for me to try out really big roles. Both of those women [the characters] were physically sick with tuberculosis, but so, so very human and flawed in a beautiful way that everybody can related to. I love exploring their characters, and the music, oh my gosh, gorgeous to sing.

Verdi, Puccini, if people haven’t had that experience of hearing that music live. And you’re down with the idea of people changing La Bohème to a thousand different time periods?

Oh up to a point, I suppose. There was a production, Anna Natrebko was singing Mimi, it was like biker gang, they had leather. I mean there is a point of diminishing returns when everyone is so distracted by the sets and the costumes. I mean opera, again, is a spectacle and people want to be taken in by the beauty and the mystery and not necessarily smacked in the face with what they see walking on the street every day.

But in addition to spectacles, with your album, you’re also really targeting more of the salon atmosphere.

Yes, that’s when you can start to take chances. And someone I trust as much as [my pianist] Henry, he’s going to be right there with me. You can feel the pulse of the audience if you have them in the palm of your hand, it’s much easier can try something new, hold that super-high note really, really soft even longer to make a phrase connect that you’ve never done before. It’s exciting, rather than saying like oh, we’re doing this song again, it’s like, no, what can we do differently with this this time?

You can sense the air moving or stopping in the audience?

You can just feel it in the room. To me one of the most magical things that happens in a performance is that moment when the piece ends and it’s like time stands still. That’s my favorite part where everyone is kind of holding their breath, they know it’s done, but nobody wants to move and break whatever spell. I’ve seen recitalists just sing AT their audience, I love the idea of bringing people in, you know, this is my living room tonight and join me in this journey of beautiful poetry and song. I mean that sanctuary [at Vienna Presbyterian Church] is going to be my living room on Sunday night. I know a lot of singers who can’t stand it because people are right there and it’s a little more forgiving in a bigger space. But I love it.

LINK

Soprano Danielle Talamantes’ website.