In the week following Ari Roth’s firing as Artistic Director of Theater J, I talked with him about his vision of theater. It was a topic that mattered to me personally, because I had come to a deep appreciation of his programing. Though I am not Jewish (I’m lapsed Lutheran, of German-Norwegian ancestry), the work I experienced at Theater J had unusual impact on me—so much so that Theater J had become for me the most intellectually challenging and morally engaging theater-producing organization in town. I wanted to know why that was. I wanted to understand how Ari Roth makes his programming choices.

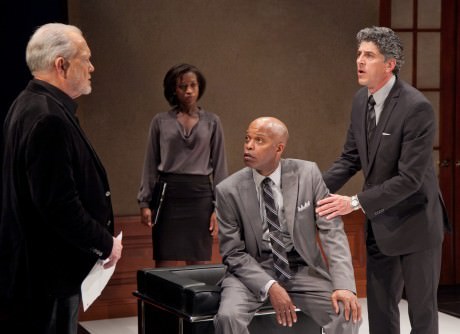

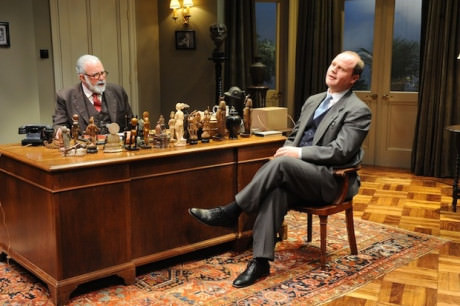

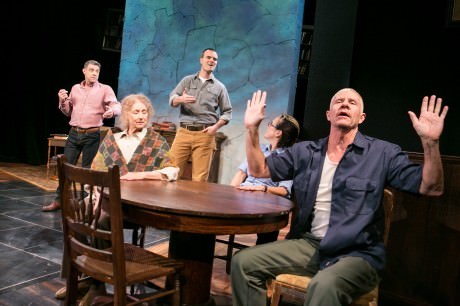

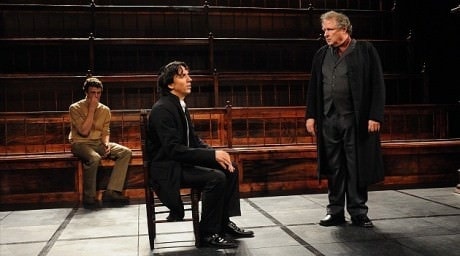

Ari has spoken of his commitment as an artistic director to “bridge building” between Jews and non-Jews. I’ve witnessed profound expressions of that commitment in work I’ve seen at Theater J—not only Motti Lerner’s The Admission, which dealt with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but also David Mamet’s Race, which exposed black-white tensions in the work place; David Henry Hwang’s Yellow Face, which confronted discrimination against Asians in theater; Mark St. Germain’s Freud’s Last Session, which took a deep dive into the theological/philosophical argument between Christianity and atheism. The list goes on, with an amplitude of conviction, and an encompassing vision of theater’s role in society, that recent contentiousness about Roth’s programming choices pertaining to Israel and Palestine has largely obscured.

Of all the art forms, theater is best suited to deal with intense and seemingly intractable social tensions. Though it cannot always point to, much less prescribe, tactics and strategies for resolution, it can vividly embody in dramatic form the heartbeat of the issues that divide us, and thereby shine a bright light on what those issues are. Under Ari’s artistic direction Theater J has done that more consistently than any other theater in town.

I spoke with Ari by phone from Chicago, where he was visiting family. Despite the saddening turn of events that had left him out of his job at Theater J, he seemed in a relaxed, reflective, and positive mood. When I asked him how he was doing, he expressed appreciation for the support of his family, and for the overwhelming show of solidarity coming his way from the theater community in Metro DC and across the country.

John: You’ve spoken of how being the child of Holocaust survivors has informed your commitment to “bridge building.” Would you say more about that, and how you came to express it through theater?

Ari: I started this dialog work because it was built into the thematics of a play I wrote in 1990 called Born Guilty. I was commissioned by Zelda Fichandler [a founder of Arena Stage] to adapt Peter Sichrovksy’s book of interviews with children and grandchildren of Nazis. The play I wrote rethought the book. It became not just a vivisection of the ugly, tormented psyche of the children of perpetrators, but it became an act of dialog on the relationship between a child of a Holocaust refugee and the children and grandchildren of Nazi perpetrators.

That play was produced at Arena Stage in 1991 and even more significantly off-Broadway in 1993. And I got very involved back then in the programming around the play. In the book and in the play there was a recalcitrant 17-year-old student named Stefanie who refuses to except the politically correct curriculum that the German high school teacher is ramming down the throats of the students. She says, basically, “Why are you blaming me? Always us the evil Germans, fear the Germans. We’re sick of it. I didn’t kill anyone, I’m seventeen years old.” She refused to be “guilted” into subservience for “we did something wrong.” This was a sensational rebellion that aroused a lot of reaction in the German public when the book was serialized in Der Spiegel magazine in 1988. The same impact happened when I adapted Stefanie’s rage into a classroom scene combining a lot of different characters who were interwoven into a dramatic scene.

We created a forum at the American Jewish Theater in New York in 1993 called “Answering Stefanie.” The panels featured folks from many different walks of life. There were Jewish historians. The founder of the Guardian Angels [Curtis Sliwa] was there. We had theologians from various Christian backgrounds. We had other children of perpetrators who had resettled in New York. We had other children of survivors. We had psychologists, civil rights activists expanding the conversation to talk about descendants of slaves and slaveholders. So this became an intercultural, interfaith conversation prompted by a provocative play. That production did extremely well and extended in New York, and the discussions around the play continued. I was just a playwright at the time and a lecturer at the University of Michigan. And this got me started on plays as their own interesting, constructive provocation, laying the groundwork for important and very soulful conversations thereafter. That is the formula and the bedrock for everything I’ve been doing since.

I’ve had a sense of theater as being the art form that’s most suited to ethics. That is, it’s about action. You have to bring your conscience to it.

You said that well. Right.

You have to bring your conscience into the theater, and the theater has to meet you—

—So that it’s not all talk. A theater that’s all talk is a theater that is devoid of dramatic action. And so the actions that characters take are a surrogate for actions the audience takes.

Thank you for that origin story of your commitment to bridge building. Do you personally have unfinished business in that regard, bridges you believe you can facilitate the building of?

All of it’s unfinished business. The new play I’m in the middle of writing is about the new generation living in Berlin today, the most multicultural and polyglot generation—Asian, South Asian, Muslim, Arab, Jewish, Israeli, Russian, and Far Eastern European children of immigrants—and how they are now forging a European identity and a German identity with the Holocaust in their past but needing it to still be inculcated into their present. A consciousness of the Holocaust is imperative if you live in Germany today. Americans are a huge step removed, from both Israel and Palestine and the Holocaust. Not so in Europe. The Israeli-Palestine drama is staring them square in the face. So that’s a fascinating touch point for me to return to. And when you say, Is there any unfinished business? Well, of course there is. And that extends to the conversation on race, as we’re seeing in the streets today. We’re in a new chapter of the civil rights movement. We’re in a new chapter of racial unrest in this country.

I’m very interested in identities that derive from membership in a perpetrator class. Once your sense of self is locked into a class that exists as a class because of what it has done to some other caste, how does one form an identity that has ethical integrity?

Right. When you’re talking about ethics and what trajectory and direction we are moving in, and might move in, the real question is, What’s informing my impulse to continue this encounter, to continue this effort to build bridges? And for me it’s that there’s an imperative to reconcile, not an imperative to exact revenge. As we carry our identities with us from the perpetrator or the survivor or the bystander class, we have different choices. One is to mete out justice and insist on accountability and fight for security and fight for a turning of the tables for a new kind of equity. All of that I can identify with. And yet more central to me is the impulse toward truth and reconciliation—accountability and then a building on that to create a new, more just, and more utopic reality—because of my parents’ story, which is one of being catastrophically displaced, and losing so much. They’ve gone on to experience a lot of fortune, still haunted by all the loss, but there’s been a lot to be proud of and a lot to make peace with in terms of a community of others, not just a community of one religion, one background. For me there was a happiness growing up on the South Side of Chicago in a demographically mixed community, full of change, full of turbulence, but also one of building a kind of new community where there could be a certain thrill in the intercultural experiment. That’s what I’m looking to create in terms of new community, and communities overlapping—both when we’ve been at Theater J and when we produce next year at The Atlas with Mosaic Theater.

Hearing you talk about this, Ari, is helping me understand why I was so drawn to, and moved by, what I saw at Theater J, especially this last season when I went to everything. I wanted to figure it out: Why is this theater different from all others?

You’ve just said it. Why is this theater a little different? Well, it’s coming from a very personal impulse that then gets extended and refracted through multiple prisms, many different authors’ points of view, but it’s all variations on the same value system. You identify with it for your own very personal reason.

I do.

But it’s the same origin story.

I’d like to bring in a comment you made, to understand it. You said in an interview, “I’m drawn to plays that touch the third rail.” How do you reconcile touching the third rail and—

—I would say that that’s in a way a hyperbolic, slightly inaccurate statement, in that I don’t think it’s the third rail. I think it’s a charged rail. When you touch the third rail in the New York City subway system you risk getting fritzed; you risk dying. But if you touch an electrically charged, dramatically charged issue—which may be the stuff of the nightly news, which is all we’re talking about, the nightly news in Israel or Germany or the United States—when you’re touching live-wire issues, dramatists don’t die. They often hit pay-dirt. That’s what we’ve done.

I’m not looking back on my programming and saying, Oh, well, I died doing it. I think what we’re seeing from the field and from the community is a tremendous amount of affirmation. The fact that the CEO of the JCC was threatened by some of this programming is immaterial to me from my assessment that the work we were doing was effective and was important.

I have a personal mantra, Ari, and it’s “If you haven’t caught shit, you haven’t done shit.”

Right. I think it does come with the territory.

The fact that after eighteen years it’s time to move forward, I’ve sensed that as well. I think that the association with Theater J and the JCC has been a constructive and a good one. The fact that it ended the particular way it did was just stupid—and hopefully will be in some ways remedied. But that was just boneheaded, in terms of the timing and the manner. That will become a minor part of the story.

Looking back at your seasons, what works that you’ve chosen to produce stand out in your mind as high points that particularly fulfill your vision?

I am somebody who’s very invested in institutional memory and the trajectory of the theater in general. I go back to the very first production I did there, Waiting for Lefty/Still Waiting, a reanimating of Clifford Odets’s labor-strike play, Waiting for Lefty. Interwoven and framed around it was Still Waiting, a brand-new piece that I created together with the director, Shira Piven, and her husband, who’s now the very well-known film director and producer Adam McKay. Adam at the time was head writer for Saturday Night Live. He contributed two incredible scenes, and then Joe Roland, one of the actors, scripted a great monologue. Waiting for Lefty/Still Waiting is about the labor movement at the end of the twentieth century, and the place the Jewish community finds itself having been part of that progressive movement to create dynamic labor unions in this country and other times part of a privileged class that fought the progress of labor. That was all dramatized in that very first play, so there have been critical touchpoints along the way.

In 2000 we launched our first Voices From a Changing Middle East Festival, and David Hare’s play, Via Dolorosa, was a major production for us. It gave rise to the Peace Cafe. We met seventeen times in the JCC in that month alone, November 2000, in the teeth of the second Intifada, when there were dive bombings happening, and we had this kind of talking cure that was launched by Andy Shallal, Mimi Conway, and myself. We had lots of facilitators from George Mason University, the Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution. All over the city we were making real headway bringing different people together to experience David Hare’s sojourn through Israel and Palestine, asking all these questions about what is the way forward and then talking about it, while outside in the world there was the bleakest of news about what was happening in Israel. We were trying to create and sow bonds of candor and trust and civility amongst a mixed group of people within the JCC. This is what we were doing. We insisted on keeping the doors open to the 16th Street lobby even after 9/11, when the JCC for security reasons wanted to close those doors at all times. We were the only program for all these years to insist on keeping those doors open so that symbolically the community could come and be welcome and not walk through metal detectors and not walk through barriers in order to get into the Center.

That festival saw us commission the English translation of Motti Lerner’s play The Murder of Isaac, which was his Marat/Sade-like meditation on the murder of Yitzhak Rabin. While we didn’t go on to produce the play—really for stylistic reasons—we were instrumental in getting it produced at Baltimore Center Stage in 2006. We brought our Peace Cafe out to Baltimore and began a partnership with Center Stage that continued with The Whipping Man, which was another bridge-building play, between blacks and Jews, looking at the Civil War and the legacy of slavery and Jewish slaveholders.

Along the way, John, I could rattle off a lot of really, really significant productions. We had world premieres by writers of major standing—Wendy Wasserstein’s Welcome to My Rash and Third, Joyce Carol Oates’s The Tattooed Girl, Robert Brustein’s Spring Forward, Fall Back, Ariel Dorfman’s Picasso’s Closet, Richard Greenberg’s Bal Masque—all of which happened in a concentration of three years—and Thomas Keneally, who wrote Schindler’s List, his follow-up Holocaust drama, Either Or, about Kurt Gerstein, the Nazi officer who went to the Pope to protest what was happening in the concentration camps.

These were really important productions, though within all those world premieres, there was nothing close to a perfect script. But we kept perfecting these wonderful plays, incredibly proud of each one. So that cemented a reputation of working on ambitious new plays with major writers.

And it was just as important for us to then move to work with emerging writers: Jeannette Buck’s professional debut play, There Are No Strangers; Stephanie Zadravec’s professional debut, Honey Brown Eyes, about the Bosnian war; Sam Forman’s professional debut, The Rise and Fall of Annie Hall, and his follow-up, The Moscows of Nantucket, and he’s now writing for House of Cards. Launching professional playwriting careers: Jacqueline E. Lawton’s Locally Grown world premiere, The Hampton Years; Renee Calarco’s play The Religion Thing, and now we’re very excited about her follow-up to that, G-d’s Honest Truth, which begins rehearsals in February.

All of these are very significant statements about playwriting, our faith and belief in the voice of the dramatist. And you know to have worked with David Henry Hwang and Tony Kushner and Alexandra Gersten-Vassilaros and Jacquelyn Reingold when we did her String Fever—just looking at these fantastic playwrights who’ve been a part of us for all these years, and to have developed deep relationships with them—has been really meaningful.

When you’re reading plays—and like many artistic directors, you must read a lot—how does your being a writer yourself figure in? How does that inform your taste and judgment about the plays by others you want to put on and the writers whose work you admire?

Trey Graham wrote an article about Theater J in 2005 for the New York Times and said a lot of nice things in the piece, but the most truthful statement I have there was “We specialize in artists with war wounds.” My sense of identifying with the playwright’s struggle connects with my looking for an authenticity of the playwright’s voice. Playwrights who do the work, who do the deep research—whether they are researching their own conflicted souls or they are researching the terrain that they’re dramatizing—the most important things for me when I read a script are voice, rhythm, how well written are those first ten pages, how animated, does text fly off the page, does it grab you by the lapels? I can tell that pretty quickly. I actually don’t like reading scripts, because they’re so frequently a boring experience, but there’s nothing better than a thrilling read you can’t put down. That’s what we live for. You’re looking for writers who can grab you by dint of the urgency and that talent that comes flying off the page or off the screen. So I read plays with a deep sense of identifying with the writer’s journey and the writer’s struggle but also the writer’s excitement.

Are there any other theaters in the U.S. that are doing a kind of programming that you aspire to and admire?

There are playwright-driven theaters that excite me—from Emily Mann [artistic director of the McCarter Theatre Center for the Performing Arts], who’s becoming an increasingly good and important friend to me, to Carey Perloff at the A.C.T. [American Conservatory Theater] in San Francisco, to local playwright Randy Baker, who together with Jenny McConnell Frederick is running Rorschach Theatre. And there are great ensemble theaters, like Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago or The Civilians in New York. Or great flagship theaters, like The Public Theater, that energize me. Or amazing theaters that specialize in new work exclusively, like Playwrights Horizons or Manhattan Theatre Club, where you kind of drool with envy but also seek to emulate that kind of devotion to the new and the new only and not have to interlace things with contemporary revivals of hits that happened elsewhere. I think there’s a kind of disappointing formula that involves interlacing new work with more familiar titles and plays that have a New York buzz. And that’s certainly what the Washington community has spoken about with its feet and its pocketbook. You can’t succeed doing only the new in this town. For every world premiere, you need a Freud’s Last Session. For every bracing political drama you need to have The Chosen woven in there. I view those hit productions, which brought in a lot of new people to the theater, as a necessary tent pole to hold up your tent, your shelter. But I envy theaters that don’t need that.

Talk about Mosaic Theater Company—your plans, hopes, dreams. What will it offer audiences who are familiar with how you curate?

Well, I don’t want to speak with too much authority or assurance of what it will be, because I’m still trying to get buy-in from stakeholders and to formulate this collectively as opposed to individually. We’re sort of banging out a mission for legal purposes as we incorporate as a not-for-profit entity with the city, and then get a board of directors going in January, and apply for tax-exempt status with the IRS. The vision, the values, and the mission are things that we’re going to be putting together in January. You can intuit that there’ll be a lot of continuity with what we’ve had at Theater J. But we’ll be moving out of the Jewish Community Center and into a secular center [the Atlas Performing Arts Center], in a teeming, complex, gentrifying (for better and for worse) neighborhood, the H Street corridor, which is just going through enormous change. There’s a lot not to be presumptuous about, not to assume we know what the issues are going to be. We’re going to be new neighbors, new residents there. So I don’t want to presume language about what our mission and vision is going to be. It’s all going to be refined through a group process over the next months.

The name Mosaic is wonderful. Has it been on your mind for a while?

It became official the day I was fired and we decided the story of my being terminated from Theater J was not going to be just “I’m leaving for new possibilities.” We’d been talking for about six months about starting a new theater company, hoping to have a graceful transition as we individuate from the JCC. And on the list of names there was Public Square Theater, the DC Public Theater, Build a Bridge, A More Perfect Union, A More Perfect Home, Shelter from the Storm—any number of names that were fun to bandy about. But I began to think about how important the name was in preserving the Voices From a Changing Middle East Festival, which within the context of the JCC promised an expansive conversation about the Middle East, but it was always understood implicitly that Israel would be at the center of that conversation, that the variety of the Israeli expression—playwrights who were writing political work and playwrights who were writing about society and family and very interpersonal issues—intersected and reflected on the experience beyond its borders. Lebanese, Palestinian, Egyptian, Iranian, Iraqi, Afghan, Pakistani voices all had a contribution to the Voices From a Changing Middle East Festival, but it was rooted in the Israeli drama. Now when we were bringing that to Atlas, the question would be, What message are we sending to the Jewish community that our identity in creating a more multicultural and intercultural theater community is still going to have a Jewish inflection to it? Israel will still be a very important component of what we do. There’s so much support and there’s such a base of engagement within the Jewish community, how can we be both a secular company and still a culturally specific company? And so that needed to be reflected in the name. With Mosaic you get it both ways. You get a Mosaic tradition from the Bible, and you get a multicultural paradigm.

I wish you well. I hope we can talk again when there’s more to be said about that theater company. It’s great to hear you talk about your vision and your commitment and your conscience. I’m very grateful.

Thanks, John, I appreciate it.

LINK

Read all the articles and news related to Ari Roth’s dismissal.

Great summary of the past and what to look forward to.