There is a shibboleth shared by liberals and conservatives alike that when a young black man shoots to death another young black man in the inner city, the fault lies in themselves. Something about not lifting oneself up by one’s bootstraps. Something about not stepping up to one’s responsibility. Something about being shiftless.

For folks who frame the blame this way, these are comfy explanations, ways of looking at a problem without the inconvenience of having to see why it actually is one. As a commitment to keeping complicitly blinkered, it’s akin to thinking of a woman who was raped that she was asking for it.

In an essay titled “The Secret Life of Inner-City Black Males,” Ta-Nehisi Coates names this pervasive pseudo explanation “the notion that black people are lacking in virtue”:

From the president on down there is an accepted belief in America—black and white—that African American people, and African American men in particular, are lacking in the virtues in family, hard work, and citizenship:

That is because it is a message that makes all our uncomfortable truths tolerable. Only if black people are somehow undeserving can a just society tolerate a yawning wealth gap, a two-tiered job market, and persistent housing discrimination.

I mention this background in order to foreground a point about Marcus Gardley’s powerfully poetic The Gospel of Lovingkindness, which has begun a run in a stunning and intimate production at Mosaic Theater Company. Just as Mosaic’s season opener, Unexplored Interior, opened our eyes to the Rwandan genocide, The Gospel of Lovingkindness opens our eyes to America’s most cherished myths about so-called black-on-black crime—and explodes them one by one as its wrenching human drama unfolds.

The Gospel of Lovingkindness is performed by four actors in the Lab 2 space at Atlas—miniature compared with Unexplored Interior, which filled the Lang stage upstairs, but no less major, and every bit as necessary.

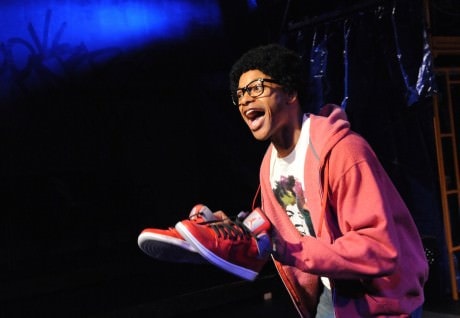

The play is set in South Side Chicago a few years ago and tells parallel stories of two young men named Manny and Noel. Manu H. Kumasi plays both roles with extraordinary physical precision and emotional range.

Noel’s mother, named Miriam, is one of several roles played by Erica Chamblee, who with consummate skill creates each distinct character. Doug Brown plays Manny’s father, plus other roles, and he too differentiates multiple characters compellingly.

Deidre Lawan Starnes plays Mary, Manny’s mother, throughout—and her emotional arc once her son is killed becomes the chilling spine of the story. Weeks after singing at the White House, Manny is shot a few blocks from home, and his prized Air Jordan shoes are stolen. Thereafter all that is senseless about his killing becomes the thread of tough truths and revelations followed ruthlessly by the play.

Director Jennifer L. Nelson has shaped an ensemble whose acting is so real and virtuoso—and staged the work so close up—it’s as if the characters in the playing area and we the audience around it share not only time and space but heartbeats and respiration. Gardley’s script contains awesomely poetic monologs, gorgeous verbal arias and disturbing riffs. Especially when Nelson has an actor stand upon a box to deliver them as if at a poetry slam, the effect is breathtaking.

Noel’s basketball coach played by Brown dashes his hopes for an athletic scholarship, assessing him “average,” but gives him a Horatio Alger-esque pep talk: “You want to survive in this world you got to stand out. Be relentless.”

With similar self-improvement aphorisms, Noel’s mother Miriam tells him to get a job: “You can take your life and rewrite it,” she urges. But harsh reality hits when Noel’s low-paying job stacking boxes falls through. And then he learns he has fathered a child whom he now must help support.

The word racism is nowhere in the script but it’s between all the lines. “The whole world’s afraid of me and they don’t even know me!” pleads Noel. “I spend so much fuckin time tryin to convince people who I’m not that sometimes I forget who I really am. I just…I just want a fair shot.”

In a brilliant coup de théâtre, Gardley brings on Ida B. Wells, the legendary Civil Rights Movement leader and women’s suffrage advocate—and Chamblee brings a spry spirit to the insightful and inciting 152-year-old. Ida inspires and emboldens Mary to be an activist in her own right and join the cause (“A million mothers to stop the killings!”), which Mary does, at first reluctantly then with zeal. And as Mary speaks out on a radio show, she connects killings to the wealth gap: “You can’t help make the streets safe if you don’t give people better options.”

In a harrowing-to-hear monolog, Noel vents what it means to live on the down side of that wealth gap:

I’ve been doing the right thing most of my life and it’s got me nowhere but right where I started. I’ve tried everything: I don’t have a head for books or numbers—school ain’t my thing. I don’t want to go to the service because I ain’t tryin to die for a country that still treat me like a lower class citizen. I tried getting an honest job, tried to make a little money the honest way but it was pennies and I just can’t spend my whole life poor as shit….

Been runnin all my life tryin not to be a statistic, a stereotype. But I keep running into the same wall. Ain’t no way I can write myself out. I just need to accept my plot. Them white boys on the North side, they get a free ride—they born with a silver spoon in their mouths—they already got their money. They already got a free pass.

There is a touching moment when Mary tucks Manny into bed as a boy and sings “Brown Baby” as a lullaby to him:

YOU GONNA HAVE THINGS I NEVER HAD

WHEN OUT OF COLD HEART HATE IS HURLED

SUGAR BROWN YOU GONNA LIVE IN A BETTER WORLD

BROWN, BROWN BABY

And there is an immensely moving reprise when Noel sings the same song to his baby son:

BROWN, BROWN BABY

YOU GONNA GROW UP

TO DRINK FROM THE PLENTY CUP

YOU DON’T HAVE TO BE TALL TO STAND PROUD

OR SPEAK UP CLEAR AND LOUD

The hope, hurt, and longing in those echoing lullabies is the heart and soul of this beautiful play. And the sharp reality check scripted into it is what makes it essential to see and feel.

That the stagecraft seems makeshift seems perfect for the visceral emotions. Heather C. Jackson’s character-disclosing costumes, Dan Covey’s living lighting, and Baye Straightforward Harrell’s eloquent sound create a world where real people say real things bluntly and unabashedly. And Set Designer Ruthmarie Tenorio has painted the walls with murals, one of which is graffitied, “If anyone finds this, I’m sorry you’re here.”

The Gospel of Lovingkindness is not to be missed. Washington, DC, needs this play. With The Gospel of Lovingkindness, Mosaic continues to build on H Street a theater with unmistakable conscience and indispensable vision.

Running Time: About one hour 45 minutes, with no intermission.

The Gospel of Lovingkindness plays through January 3, 2016, at Mosaic Theater Company of DC performing in the Lab 2 space at Atlas Performing Arts Center – 1333 H Street NE, in Washington, D.C. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 399-7993 ext. 2, or purchase them online.

RATING:

I agree . It was a great show ,very powerful and well directed and acted.