Yes, Virginia — and DC and Maryland also — this West Side Story is Real.

A Real Masterpiece. Even more, perhaps a Christmas miracle, in Shirlington Village.

It’s just that good.

Considered by many, indeed perhaps by most, rightly to be America’s incontestable “Best Musical” ever, yet it is only now staged for the first time at Signature Theatre in Arlington, Virginia. And this soaring smash-hit is quite simply stunningly triumphant. At a theatre company justly famous for its revivals of the classics, this one stands tall as Signature’s magna cum laude of revivals.

This rock’em-sock’em show re-imagines and re-stages this most simple (on the surface) tale of boy-meets-girl, playing on the intimate Max Theatre stage of Signature Theatre (in Shirlington Village) through January 24th. It’s so intimate you feel you might get socked yourself during the fight scenes. No one sits more than five rows back from the action, which spills over the edge of the thrust stage, surrounded on three side by the audience. No tame protective proscenium arch will contain this action and keep these dancers and singers from getting right in your face.

The show sparkles with high notes of singing and low moments of dramatic angst. It’s flecked with violence, stamped with hatred, yet salvaged by optimism. It is of course the iconic re-telling of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, where purest love falls final victim to death’s dominion. Sensuous yet also sensitive, this love story of star-crossed Tony and Maria, members of rival respective ethnicities (white and Puerto Rican), finds them caught in the knot of blind hatred.

This is Catch 22. No matter what they try, their love is doomed from the start, a fatality of the crossfire of gang warfare in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen, on the borough’s West Side in the 1950s. Make war, not love. That’s the driving beat of the street. How can Tony and Maria ever hope to survive this?

Their duet, “One Hand, One Heart,” tells us all we need to know about their love. Tony’s solo, “Maria,” is sung straight from his heart, the first flush of romantic love, the same flush of desire Romeo felt in Verona when he first laid eyes on Juliet.

This is of course the musical which does not end well. Everyone already knows that. Instead, the joy of life — exultant at first in young love — must die finally, in its tearful and tragic ending, when cathartic sorrow succeeds the bliss of love’s first bloom. With a bitter cry strangled in your throat, the sole consolation that remains at the end of West Side Story” is this: to accept that this grief is and must be universal. All love must end, one way or another. It must end in this broken world of hatred and violence, with ashes to ashes, and dust to dust.

Let’s face it too — as an adaptation of one of William Shakespeare’s most popular plays, it’s not too shabby in its original version.

But here and now, let’s turn to the play itself — and how it came to be.

Every great mythology has in its origins a topic for much speculation — whether Superman from the planet Krypton, or Scully and Mulder in The X-Files, or Han Solo and Chewey in Star Wars. And so it is also with West Side Story.

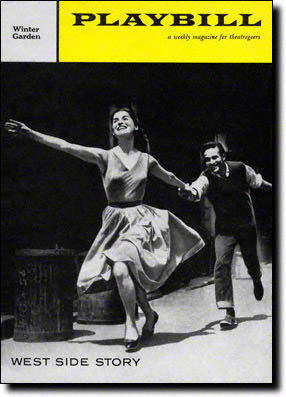

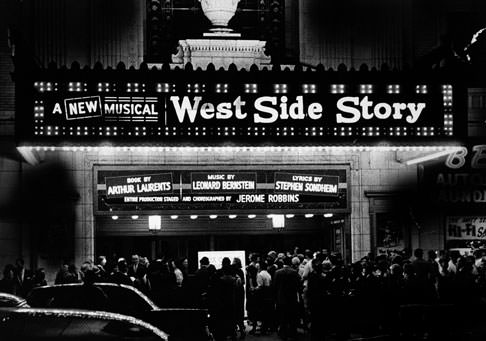

As for its origins, this musical play –which opened on Broadway in 1957, to be followed in 1961 by the film version — is heaped with highest honors in its parentage.

First, of course, there’s the Book by Arthur Laurents, whose musical-theatre body of work also includes Gypsy (1959) and La Cage Aux Folles (1983), and in addition film scripts for the likes of Alfred Hitchcock (Rope, in 1948), and for Anastasia in 1956, The Way We Were (1973) and The Turning Point (1977). That’s a resume to conjure with!

He was born Arthur Levine in 1917 in Brooklyn, the son of middle-class Jewish (albeit atheist) parents. His Bar Mitzvah marked the end of his religious education. Although he continued to self-identify as a Jew, late in life he admitted to having changed his surname from Levine to the less-Jewish-sounding Laurents, in order, he said, to “get a job.”

After graduating from Cornell, he took an evening class in radio writing at NYU, where his instructor was so impressed that he submitted a Laurents’ script — a comedic fantasy about clairvoyance — to the CBS Radio Network, where it was produced with actress Shirley Booth in the lead role. It was Laurents’ first professional credit but would not be his last. In the middle of World War II, he was drafted, so his career was interrupted, but not really, as he was assigned to the US Army’s Pictorial Service located in a film studio in Queens. There he would meet, among others, the director George Cukor, who became an early mentor, and the young actor William Holden.

Summing up Laurents’ career (he died in 2011, aged 93) much later, one writer said that “Laurents was always a mirror of his times.” Through his best work, one critic said, “One sees a staged history of leftist, gender, and gay politics in the decades after World War II.” Before long, he was not only selling scripts for production on radio, he was selling them to Hollywood, which soon led to Hitchcock hiring him to work on the making of Rope in 1948.

Upon discharge from the Army, young Laurents met and fell in love with a young ballerina, Nora Kaye, sparking a relationship fraught with great tempest, going from on-again to off-again and back-again. Meanwhile, he fell under the baleful glare of red-baiting and blacklisting. Called to testify in Washington, DC — to account for his politics, which were undoubtedly leftist — and after being grilled by the House on UnAmerican Activities Committee (the infamous HUAC), he was more or less ignored compared to the hysteria over the Hollywood 10. People like Dalton Trumbo, now the subject of an amazing film starring Bryan Cranston in the title role, soon saw their careers suffer real jeopardy. But for Laurents, whose main career was on Broadway and not in the film industry, there was little impact. He did, however, spend about 18 months traveling outside the US while the Red Hysteria, and the accompanying censorship of anything thought even vaguely leftist, peaked and then slowly begin to pass.

Some signs of trouble could be seen, however. Some years earlier, in 1948, Laurents met the young choreographer and dancer Jerome Robbins. They were to develop together a stage musical Look, Ma, I’m Dancing’, about the history of the ballet.It had a mixed reception and ran for only 188 performances. Oddly, when Robbins approached Paramount Pictures about directing a screen version, when the studio agreed, it was was with the understanding that Laurents would not be involved. Meanwhile, in 1962, Laurents wrote and then also directed for radio a production of I Can Get It for You Wholesale, notable among other things for turning a young ingenue Barbra Streisand into a star. Next came Anyone Can Whistle, which proved to be a massive flop.

His remaining career generally moved from high to high point, though it’s debatable whether this list ought to include the reunion of Laurents in 1973 with Barbra Streisand (also starring Robert Redford) for the big-budget hit film The Way We Were, that saccharine depiction of McCarthyism, with Streisand playing the young radical and its mostly rosy scenario about the very real economic costs and psychic terrors of the black list.

Toward the end of his life, Laurent decided it was time to come out of the celluloid closet. In 2000 Laurents published his memoir, titled Original Story by Arthur Laurents: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood, and he outed himself by recounting many brief gay affairs alongside several long-term ones, one with the actor Farley Granger, who was one of the stars of the Hitchcock movie, Rope, upon which Laurents had worked many years earlier as scriptwriter. Meanwhile, it was Gore Vidal who arranged for Laurents to meet the love of his life, Beverly Hills clothier Tom Hatcher. That relationship last 52 years, until Hatcher’s death in 2006.

When Laurents himself died, in 2011, Broadway saluted him with its ultimate recognition. The lights up and down the Great White Way were dimmed in his memory for one minute on May 11, 2011.

So much then for the author of the basic narrative of West Side Story — or the Book.

The choreography was of course in other hands, those of the highly mercurial but ingenious Jerome Robbins.

A virtual polymath, five-time-Tony Award winner Robbins appeared to be able to do anything at all, and always do it right. He was so protean that no single craft could encompass his talent. Theatre producer, theatre director, dance choreographer, he was known principally for Broadway Musicals and ballet and dance productions, but he also occasionally directed films and produced and directed for television. Robbins seemed to be everywhere — On The Town, Peter Pan, The King and I, The Pajama Game, Bells are Ringing, Gypsy, and Fiddler on the Roof. And of course, West Side Story.

First, there was his work on the stage musical itself Then in 1961 he shared the Oscar with Robert Wise for Best Director of the film version of West Side Story, which won 10 Oscars, including Best Picture.

Robbins was born Jerome Wilson Rabinowitz, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, in 1918 in a Jewish maternity hospital in the Lower East Side of New York City. His middle name “Wilson” was a nod to assimilation — to the man who was president then, Woodrow Wilson. Soon the surname vanished, replaced by a non-Jewish-sounding Robbins. From the beginning, he studied dance. By 1939, he was dancing in the chorus of Broadway shows, but also dancing and choreographing at a summer resort in the Poconos, where his work emphasized political themes — war, racism, and lynching. Then, in 1941, he switched to ballet and for three years he was soloist for American Ballet Theater, gaining favorable recognition for lead roles in Petrouchka and Romeo and Juliet.

Robbins was influenced greatly by trends on Broadway where shows more and more integrated the dance elements into the dramatic structure of the musical. In this regard, the Rodgers and Hammerstein Oklahoma! was a major breakthrough.

Robbins next created the dance numbers for Fancy Free, a ballet based upon the highly homoerotic painting The Fleet’s In, a famous 1934 depiction of sailors as love objects, by Paul Cadmus. But Robbins was determined to “straighten” out the gay subtext from the painting and show that sailors could love girls, not boys. Robbins later said that he “wanted to show that the boys in the service are healthy, vital boys; there is nothing sordid or morbid about them.”

No “In the Navy,” the Village People song, for Robbins!

Through the set designer on Fancy Free, the next link in the chain, drawing together the talented quartet destined to create West Side Story, began to be forged. Oliver Smith knew Leonard Bernstein, and through him eventually Robbins and Bernstein met to work out the music for a series of collaborative affairs. They grew closer still when Robbins commissioned the music for Fancy Free from Bernstein.

That same year, 1944, Robbins choreographed On The Town, a ballet based partly on Fancy Free. This launched Robbins back into a career on Broadway. Once again the composer was Leonard Bernstein.

Robbins was a tyrant in rehearsal. One story, possibly even true, is that the company of one show watched as Robbins walked backwards and then accidentally fell into the orchestra pit, and no one called out to warn him of the peril.

Meanwhile, his success on Broadway only grew. In 1950, he directed and choreographed Irving Berlin’s Call Me Madam, starring Ethel Merman. Next came The King and I — including the celebrated march of the Siamese children sequence as well as the memorable “Shall We Dance?” duet polka between the two leads — Anna and the King. He also served as show doctor when needed on several shows including, in 1953, Wonderful Town. Next came The Pajama Game, which launched the career of Shirley MacLaine, in 1954, and then worked with Mary Martin on various iterations (stage and TV) of Peter Pan. In 1957, the plot would thicken. It was time for West Side Story.

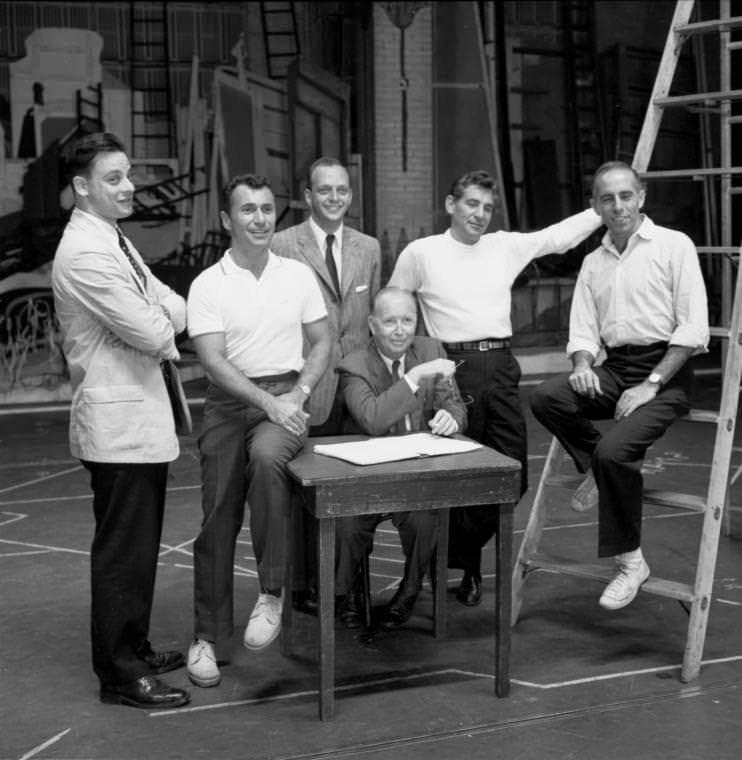

Of course Robbins and Bernstein had already been collaborators. But now they came together — alongside Arthur Laurents, who wrote the book — around this central trope: adapt Romeo and Juliet, nothing very new there. Relocate its timeless tale of young love and young death from Renaissance Italy to a rough and tough section on Manhattan’s West Side known as Hell’s Kitchen. So now they brought in their fourth collaborator, the young Stephen Sondheim, to write the lyrics.

Even though the show would open to good reviews, this Shakespeare-noir-redux was overshadowed by the Americana and sunny optimism of Meredith Wilson’s The Music Man at that year’s Tony Awards ceremony. Robbins himself would continue in top form. His run of hits kept coming – especially Gypsy, re-teaming Robbins with Sondheim and Laurents, but with music by Jule Styne.

Darkness, however, shadowed Robbins politically. The long, intrusive arm of the McCarthy-inspired probe of show business to weed out suspected Communist influences then fell on Robbins. In the early 1950s, he was called to testify (read “rat out” others) before HUAC. Robbins had long resisted snitching on others – for three years, in fact, he refused to name anyone else. But Robbins relented when threatened with “outing” him as gay. Sgueezed in this way, he broke and named names. Because of this public cooperation with HUAC, Robbins career did not suffer. What occurred within, however, can only be guessed at.

More success followed for Robbins — the 1961 film version of West Side Story, co-helmed with Robert Wise, was both a critical and commercial hit. However, Robbins – always a stickler for detail, almost obsessively so – had taken so long with the rehearsals and filming of the dances that he was fired during production, although he did still receive screen credit (and share the Oscar) as director. He was still much sought-after as a show doctor, a show-whisperer who helped to save, with an entirely new opening number – “Comedy Tonight” for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum and helped to turn this musical farce starring Zero Mostel and Jack Gilford into a solid hit in 1962. The show’s songs and lyrics were by Sondheim.

Next, in 1964, he took on a floundering Funny Girl,” and helped to save that snow and incidentally convert Streisand into a super-star. That same year he won Tony Awards for his direction and choreography of Fiddler on the Roof, which soon held the (then current) record of over 3200 performances for the longest running show on Broadway. It also allowed Robbins to return to his original religious roots.

In 1986, Robbins began to look backward over his long career, when he created the retrospective anthology show, Jerome Robbins’ Broadway, that opened in 1989 and as narrator starred Jason Alexander (later to become “George Costanza” on Seinfeld). This show recreated the most successful numbers over his half-century career. The show won the Tony Award for Best Musical.

Years of decline, however followed, especially after a bicycle accident in 1990, heart surgery in 1994, and in 1996 signs of Parkinson’s Disease appeared. His hearing was going also, though he nevertheless staged his final production, Les Noces, for NYC City Ballet in 1998. Robbins died at home in New York later that year following a stroke. He was cremated and his ashes were scattered in the Atlantic Ocean. As with Arthur Laurents a few years later, the lights were dimmed on Broadway for a minute in tribute.

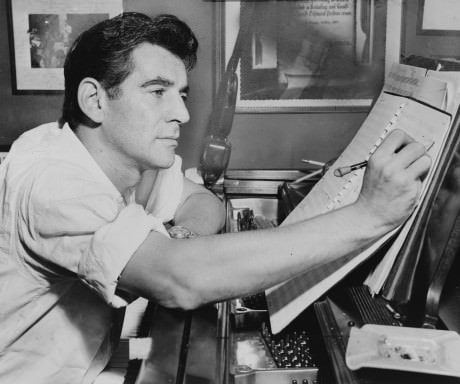

The final two members of this Million-Dollar-Baby quartet are each much better known than the two detailed here — Laurent, for the book, Robbins, for the choreography. After all, Leonard Bernstein is the Maestro. And Stephen Sondheim is, well, sui generis.

So no figurative ink will be spilled here to remember them. For that would be gilding the lily. Some attention of course must, however, be paid to the fact that all of them were Jewish and all of them were gay, or bi-sexual.

But instead, let’s explore further what happened when these four men came together to create this show. In other words, how did the magic happen? How did they catch this lighting in a bottle? It wasn’t, in a word, easy.

It began a decade earlier, in 1947, when Robbins first approached Bernstein and Laurents about joining forces to share in adapting a musical version of Romeo and Juliet. In Robbins’ imagination, it could be set in a conflict between an Irish Catholic family and a Jewish family, living on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, during the Easter/Passover season. The Juliet of this adaptation is a Holocaust survivor who has emigrated from Israel, then undergoing its epic struggle to win recognition of a Jewish national state in Palestine.

Robbins’ initial conception was to center the triggering conflict around the anti-semitism of the Jets (Catholics) toward the Emeralds (Jews). Laurents, determined to to write his first musical, immediately agreed. Meanwhile, Bernstein argued in favor of staging it as an opera — a suggestion stoutly resisted by Robbins and Laurents. What they had in mind, instead, was still inchoate, but they were calling “lyric theater.”

Laurent’s first draft was titled East Side Story. Fairly soon, he dropped out. So all four now went their separate ways. The project was shelved — for nearly five years.

Then, in 1955, theatrical producer Martin Gabel invited Laurents to write the book for a new property Gabel was trying to bankroll. Laurents accepted the offer and proposed that Robbins and Bernstein join the team. But Robbins was like a dog with a bone. If they were to reunite, he said, forget about the Gabels’ project. Instead, he argued, they should tackle the earlier project, East Side Story.

Laurents himself was still committed to the original Gabels’ project (about an opera singer who realizes that he’s gay). To that end, Laurents introduced Gabels to Stephen Sondheim, then very young and just getting started as a composer and lyricist.

Once again, things seem to have stalled. The masterpiece that is West Side Story was once again going nowhere but downhill and downhill fast, again.

Then by sheer happenstance, Bernstein, who was in Hollywood to conduct the Hollywood Bowl, met with Laurents, who was also there working on another screenplay. Soon, talk turned to their thus-far abortive effort to update Shakespeare and move the story from Verona to Manhattan, and the Montagus and the Capulets to the Sharks and the Jets.

Meeting at The Beverly Hills Hotel, Laurents and Bernstein agreed on a radical reworking of the basic idea, triggered by widening public recognition that so-called “juvenile delinquency” had become a pressing social problem in the nation’s cities. Prompted by front-page newspaper stories about teenage gangs among Puerto Ricans, the two talked and talked and swiftly they switched gears for the book — now retitled West Side Story.

Bernstein was enthusiastic in principle but first had wanted to relocate the scene to a Chicano setting — in Los Angeles. However Laurents felt he was more familiar with Puerto Ricans and Harlem. Anyway, Bernstein decided he could only afford the time to write the music, but not the lyrics. Robbins and Bernstein then determined to invite the team of Betty Comden and Adolph Green to tackle the lyrics.

So they went back to Robbins, who was excited at the idea of a musical with a Latin beat. Now he and Laurents began to focus on moving their new ideas forward. And both of them, still in Hollywood working on films, kept Bernstein, who was back in New York City, in the loop.

Next, Laurents returned to New York City, and at an opening night party for a new play, he met Sondheim, who had already learned that the Shakespeare re-make was back in play. In the latest Laurents version, the Jewish Maria had become a Puerto Rican on the fringes of a street gang. The original Laurents book had hewed very closely to the original Shakespeare, but now some of the characters and the Elizabethan elements were jettisoned.

Now the focus was growing more intense as Sondheim tossed out clunky dialogue in favor of knife-edged lyrics — sometimes just a simple phrase like “A boy like that would kill your brother” was transformed into a cutting song lyric. The song, “One Hand, One Heart,” was moved — at the suggestion of Sondheim’s mentor Oscar Hammerstein and after Laurents urged Bernstein and Robbins to agree — from the balcony scene to the one set in the beauty shop.

Laurents then turned his attention to the problem that the building tension of gang warfare needed to be somehow alleviated so as to increase the impact of the subsequent tragic ending. He argued successfully for adding the comic relief of the Officer Krupke character to the second act. On other issues the vote went against him, for example, when he argued that the lyrics to “America” and “I Feel Pretty” were simply too witty for the characters singing them. These wittier lyrics, of course, have become audience favorites from the beginning.

Bernstein was actually composing two musicals at the same time — Candide and West Side Story concurrently — so he began to move music and lyrics back forth between the two. For example, the Tony and Maria duet, “One Hand, One Heart,” was originally composed by Bernstein for a Cunegunde solo in Candide.” Meanwhile, the music of “Gee, Officer Krupke!” was pulled from the Venice scene in Candide.

Laurents would later explain how the creative team got so completely in sync with each other:

“Just as Tony and Maria, our Romeo and Juliet, set themselves apart from the other kids by their love, so we have tried to set them even apart by their language, their songs, their movement.”

The show was almost ready in late 1956. But first most of the team members had other immediate and pressing commitments to fulfill. Robbins was needed on Bells are Ringing, and Bernstein was responsible for Candide. Then, in January 1957 the latest Laurents’ play, A Clearing in the Woods, opened and quickly closed. As for West Side Story, a backers’ audition had failed to raise the needed funds, and then the show’s producer pulled out of the show. Other choices to produce had already turned it down. The belief was simply this: the show would prove to be a colossal dud. It was, most felt, simply too dark and depressing.

Bernstein was nearly in despair. Then Sondheim convinced his friend Hal Prince to read the script, and Prince liked it but was hearing others say it would be stillborn. Then Prince decided to take a risk, roll the dice and ignore the nay-sayers. He flew to New York to hear the score. Later, Prince would recall that “Sondheim and Bernstein sat at the piano playing through the music, and soon I was singing along with them.”

There’s a cliche that goes along with what was about to happen. It goes like this: The rest is history.

LINK:

David Siegel’s 5 star review of West Side Story on DCMetroTheaterArts.