It’s a lot like Ibsen’s play, A Doll’s House, when Nora sounded the door-slam heard round the world.

A similar shocking noise punctuates the end of Motti Lerner‘s new play, After The War, with the sudden crack of a piano keyboard lid slamming down hard. It’s an unsettling moment, a sound of something human breaking, a painful sound heard round the Mosaic Theater Company of DC at the Atlas Performing Arts Center, where the play is now being performed in its world premiere.

But the play has long been in gestation between Lerner, a renowned yet highly controversial Israeli playwright, as well as the play’s director Sinai Peter, also an Israeli, and Ari Roth, founder and artistic director of the new Mosaic Theater. And it’s notable, and hardly flattering to the powers-that-be in Israel’s theater establishment, that the premiere must be here and not in Israel.

That it should be at Mosaic, however, is certainly apt. Mosaic is now in its inaugural and much celebrated first season. It hosts Roth’s longtime “Voices from a Changing Middle East Festival,” formerly housed at the DC Jewish Community Center’s Theater J, where Roth was Artistic Director for 17 years. This is another of Lerner’s hotly contested plays, the seventh in fact in his long-standing collaboration with Roth, dating back to 1997 — almost always about Israel, the occupied territories of Palestine’s West Bank, and the status, mostly not a happy one, of the Palestinian Arab minority in Israel.

The play will run at Atlas Performing Arts Center through Sunday, April 17th. So there’s only a precious few more days in which to see it, and see it you must! It is a landmark work, sizzling like raw beefsteak on a hot grill, yet also not yet fully formed, still almost raw in its state of fecund incompletion.

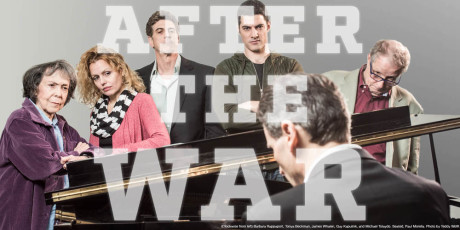

It is, in fact, admittedly still a work in progress. In places perhaps contrived, it exploits a fractured family of Israeli Jews: a sullen mother; her two feuding sons; a dodgy and wounded grandson; a perplexing girlfriend, a siren who’s almost too smart for her own good, and she’s also the nurse to the ailing mother; and — also yet another of her suitors, her somewhat mysterious ex-husband. Through a repeated round of cries and whispers, uneasy silences and brutal invective, they gnaw at one another, probing the skull beneath the skin, and the locus of consciousness itself, the soul, until the piano lid comes slamming down, snapping vulnerable flesh and bone.

That bone-crunching denouement closes out this fiercely contested family battle, this toxic shock syndrome wound tight within the DNA of this broken family and its spiraling legacy of dysfunction.

And it leaves the audience feeling battle-scarred over the return of a prodigal son, a renowned concert pianist who left Israel 18 years earlier, after openly voicing criticism of its wars — especially one in Lebanon in 2006. With Lerner’s play, we see people traumatized by decades of conflict. It’s what Thomas Hobbes once called “the war of all against all,” where compromise seems a bridge too far, and where a civil war within a family finally ends, or does it end? It leaves the title of the play, After The War, both ambiguous and haunting, begging the hovering question: when will this endless war resume?

The door-slam heard round the world — because of the shock it caused to bourgeois patriarchy and its reigning sensibilities — is of course famously associated with the lead, and certainly its most interesting, character, the house-wife Nora Helmer, who achieves a feminist epiphany after years of docile submission, in Hendrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, written in 1879 when he was living in Italy.

Ibsen, the father of modern prose drama, is a key influence on Motti Lerner. To understand Lerner’s work — and his string of serious plays about Israel and the Arabs, two of the three Abrahamic monotheistic religions, who share that troubled soil as a land torn in two, and whose blood-feud has haunted the Middle East since the forcible creation of the state of Israel in 1948 — it helps considerably to understand Ibsen also.

As for the incompleteness of this play, it helps to recall the circumstances of Franz Schubert’s Eighth Symphony, famously also “Unfinished.” He started it in 1822, but left it incomplete, finishing only two movements — the strikingly dramatic and nearly climactic first allegro movement, and the second andante movement. Though he lived for another six years, he never returned to it. A nearly completed scherzo, as a piano score, was only orchestrated for two pages, and as such it’s at most a musical fragment. Yet the Eighth remains a key symphony in the musical canon, often considered the first truly Romantic symphony, even within its essentially classical format.

Even if Lerner never “finishes” this play, it will not soon be forgotten. Like Schubert’s first movement, After The War is also discordant and climactic. It will work on you after you leave the theater as you wonder — why, and who, and what are these mostly unlikable characters doing? So troubling are the interactions, so baffling at times the motives, this play in fact ends as a kind of “in medias res,” in the middle of things.

This literary technique is as old as Homer, though it was spelled out later by the Roman poet and satirist Horace in his “Ars Poetica” (Poetic Arts) as a literary device characteristic of the beginning of a work of literature, where the action opens in its midst, not its beginnings, and flashbacks ensue and exposition is downplayed. Thus, in Homer’s Odyssey most of the hero’s journey home precedes the moment when Odysseus is held captive on Calypso’s island. The Iliad also opens in the thick of the Trojan War, not its origins when Paris (Trojan) and Helen (Greek) flee in adulterous romance from her furious and vengeful husband.

With After The War, however, the play ends “in medias res,” and the loose ends spill all over the stage. Will the protagonist, Joel, return home again, or not?

The entire play was shaped by Lerner, with the collaboration of its director, Sinai Peter, in a kind of suspended animation — changing as things developed over the years, with Roth also as one of the active collaborators, though at one point they gave up on finishing it at all. Things remained in flux while the actors were still rehearsing their lines. Lerner, in fact, was rewriting it right up until the night before its March 28th opening performance.

The play is deeply rooted in Lerner’s own life. He fought in the 1973 Yom Kippur War as an army captain, after which he rallied some 30 of his fellow students at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem to protest that war by dressing in bandages covering simulated wounds, in street theater that he has called “a performance of the dead.” They performed it on the steps of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament. Lerner, now 66, told one interviewer recently that “there was no result whatsoever,” that those who watched “just shrugged their shoulders.”

Lerner has never ceased to protest Israel’s wars. But as a dissenting voice among the country’s peace activists, and a man of the political left, he has been mostly frozen out of the political debate inside Israel. He has thundered like a Jeremiah, with a moralist’s fury. His fate in Israel has not quite reached the dimensions of Jeremiah, but he has nevertheless been a prophet unhonored in his own time and mostly unproduced at home. Jeremiah, one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible, held a mirror up to his own people — in the sixth and seventh centuries BCE — to reveal the many sins of his people and to warn of the impending disaster. God’s message to Jeremiah was simple: “attack you they will, overcome you they can’t.” And he was attacked indeed, first by his own brothers, then beaten by a priest, and imprisoned by the king, and even thrown into a cistern. At least Lerner can muse upon the fact that things in Israel today, bad as they are, aren’t quite that bad!

The basic arc of the show is simple. Joel is a concert pianist, returning home to Israel after 18 years to visit his ailing and withdrawn mother, as well as to see his own son, a soldier in the Israeli Defense Force (IDF), who’s been raised in New York City, where his father and mother have finally divorced after years of marital turmoil and alleged adultery by Joel. His arrival triggers such intra-family hostility towards him, as he’s viewed as a traitor for having accused Israel of war crimes in the case of an awful incident during the Second Lebanon War.

That war was of course simply another war in a long history of Israel’s conflict at the Israeli-Lebanese border, in which both sides quaked in mutual vulnerability and fear. The war in this incarnation began in the morning of July 12, 2006, when militants of the radical Islamist Hezbollah (Party of God) fired Katyusha rockets across the border from their Lebanese bases. Three Israeli solders died and two hostages were captured.

On July 30, the IDF launched a missile attack in reprisals on a suspected Hezbollah hideout in the Lebanese town of Qana, killing 27 civilians. No Hezbollah weapons or soldiers were ever found in the area. Amnesty International later released a report accusing the IDF of war crimes by deliberating attacking civilians. Eyewitnesses testified that no Hezbollah soldiers were anywhere near the targeted location, nor were attacks ever launched from civilian areas.

In reply, the Israeli Heritage and Commemoration Center released its own report accusing Hezbollah of war crimes for using Lebanese civilians as “shields” and targeting civilians in Israel as legitimate acts of war. In turn, a Human Rights Watch report backed up the Amnesty version, finding that the majority of the casualties at Qana and elsewhere were nowhere near any signs of Hezbollah’s military presence.

The very ambiguity of what happened at Qana is at the heart of the darkness at the center of After The War.

The play is discordant. The play is dissonant. The beauty of the music Joel plays — mostly from Beethoven’s “Pathetique” piano sonata — stands in stark counterpoint to this post-war family discord. It echoes the wisdom of the English poet and playwright of the Restoration era, William Congreve, in his tragedy The Mourning Bride (1697), a tale of love and deception, murder and suicide, when he observed what Lerner recapitulates: “music has charms to soothe a savage breast.”

The music, however, fades away, and what’s left are broken fingers and a family worn away by what Lerner has called a post-traumatic syndrome throughout much of Israel today. All of those wars, all of that trauma, has led to this horrible conundrum and this horrid tragedy. Like scorpions in a bottle stinging each other, Israel — under the misrule of the man determined to block reconciliation with the Arabs, Bibi Netanyahu — and the Palestinians — those under the thumb of Hamas in the Gaza Strip and those under the Fatah-ruled Palestinian National Authority in the occupied territories of the West Bank, established in 1994 — can neither make peace nor win a war.

Neither can the family in Lerner’s sadly true play.

After the War plays through April 17, 2016 at Mosaic Theater Company of DC performing at Atlas Performing Arts Center – 1333 H Street, NE, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 399-7993 ext. 2, or purchase them online.

LINK:

Magic Time! ‘After the War’ at Mosaic Theater Company of DC by John Stoltenberg.

I found the play left me very unsatisfied

I had no clue as to why the mother reacted and changes her reaction and changed yet again. The characters seemed shallow and undeveloped and when toward the end, they seemed to all agree and challenged the pianist ability to play, I felt the play fell apart. The reviewer points out that this is a work still in progress but perhaps it’s debut should have waited.