There’s good news and bad news floating out of GALA Hispanic Theatre this week.

First, the bad news.

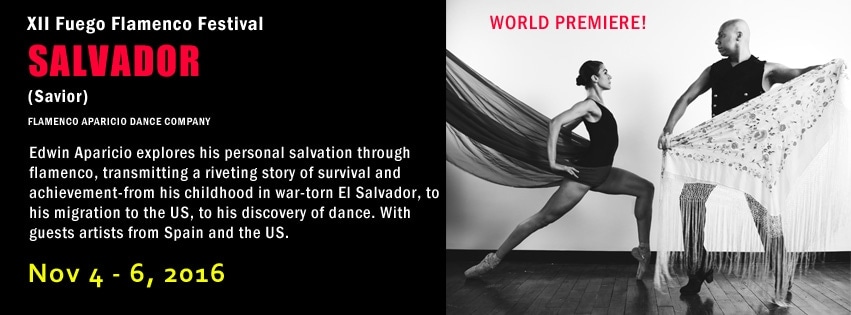

Salvador—the full-length autobiographical dance drama, choreographed by the great Flamenco dancer, Edwin Aparicio, and directed by him and Aleksey Kulikov—has come and gone.

The world premiere—which marked the opening of the 12th annual Fuego Flamenco Festival, co-founded by Aparicio and curated by him—drew a cheering, foot-stomping ovation so loud the sound must have rocked the walls of the landmark Tivoli Theatre in Columbia Heights.

Now the good news.

This Flamenco narrative—told with traditional sound and movement, yet wildly unconventional—is so powerful, and so brilliantly staged and performed, that it is bound to be resurrected soon. My guess is via the Washington Ballet (hint, hint), since one of their principal dancers, Sona Kraratian, is one of Salvador’s stars.

The word ‘Salvador’ means saviour in Spanish, and this Salvador is the story of Aparicio’s salvation.

The drama unfolds in three acts, beginning in El Salvador, where civil war threatens to rip apart the country. Aparicio survives, protected by his grandmother in the town of San Miguel until even that haven is too dangerous. At the age of 10, he is sent to live with his parents in America.

Act II is set in Washington, DC, where new terrors await. This time, Aparicio finds salvation in ballet. He escapes the menace of the streets, but is urged to try another form of dance.

Act III finds our hero in Spain, where flamenco—a centuries’ old art form that combines singing, dancing, clapping and guitar—provides the ultimate salvation.

The dance opens, improbably, with silence. It is an ominous silence, lasting for three minutes. Lights focus on an empty stage and tension builds.

Slowly, a procession of women, each holding a candle aloft and dressed in funereal black, enters. The principal dancers—Genevieve Guinn and Alexa Miton—perform a solemn Lament (saeta), accompanied by the wailing voice of Amparo Heredia.

In War Dance (siguiriya), Norberto Chamizo displays a terrifyting ferocity as he leads a band of warriors, dressed like blood-streaked cannibals, while Francisco Orozco, the singer known as Yiyi, chants them into a frenzy. Jose Viñas plays Edwin, a boy trying to escape his captors.

At home, his fears are calmed by his grandmother in Lullaby (nana), where Heredia sings the child to sleep, then bids him farewell in the following number, Goodbye (malagueña).

A grown Aparicio appears. He dances the pain of leaving to the sound of Yiyi’s voice and Gonzalo Grau on the cello while his younger incarnation looks on. It is overwhelmingly sad.

Act II opens with Welcome, as the family reunites in Washington. Young Edwin—again danced by Jose Viñas—joins Alexa Miton. But the gringos in Mount Pleasant are not welcoming. The dancers, holding white masks, reject the new arrival.

In Hermanos (jaleo), new threats emerge. Seeking out other Latinos, Edwin is briefly drawn into street life as the locals, hiding in their hooded sweatshirts, try to make him one of them. Once again, Chamizo seems to be Satan incarnate as he dances the role of street lord. Miton and Guinn circle round.

Like War Dance in Act I, this is a terrifying dance that clearly evokes the peril facing the immigrant who is trying to belong. Edwin escapes, finding safety in the study of ballet.

Terpscihore, so named for the muse of dance, is one of the most dazzling numbers in the show.

Choreographed and performed by Sona Kharatian, a principal dancer with the Washington Ballet, Terpscihore is a brilliant pastiche of 19th century Russian ballet, combining hints of the classics, inspiration from Satie and a taste, at the end, of flamenco.

Kharatian, who studied at the Kirov, displays exquisite technique as she prances sinuously en pointe, trying to teach the elements of ballet to Edwin, who is her student. Together, they perform a duet that is actually a spoof of classical ballet. Choreographed by Aparicio and Kulikov, the dance is a tour de force for both the prima donna and Viñas.

Act III finds Edwin in Madrid, where all the principals gather on stage for Amor de Dios, a fiery introduction to tango and traditional flamenco. This time, Chamizo is the teacher, leading his charge into the penultimate Coming of age (solea).

In the finale, the real Aparicio returns, accompanied by both singers and his collaborator. Together, they reprise several earlier numbers from the show. (Kulikov, who is from Kiev, does a flamboyant flamenco, adding a touch of Russian bravura to the multi-national production.)

Aparacio then concludes with a show-stopping solo performance that is both breath-taking and mind-boggling.The night I was there, the audience, spellbound, roared with applause.

Salvador is an electrifying moment in the theatre, thanks to Aparacio and his collaborator, Kulikov, who is also his longtime partner and husband. (The two were married in 2013.)

Together, they have assembled a cadre of artists from all over the world—with dancers and musicians hailing not just from Spain, as one would expect, but also from France, Germany, Venezuela, Bulgaria, Armenia, and the US—as well as a production staff that includes many talented members of the GALA Company.

The names of Alberto Segarra, who designed the extraordinary lighting effects, and Reuben Rosenthal, the technical director, will be familiar to many GALA regulars. Thanks to them, the battle scenes are especially vivid, filled with the smoke of gunfire, the illusion of spattered blood and the photographs, projected onto the scrim, of victims of the war ,

Anna Menendez, who, has been a principal dancer in many GALA productions, is the assistant director who works closely with both stars to ensure a seamless production.

The composer and music director—who also plays piano, keyboard, cello and guitar—is Gonzalo Grau, whose work has been commissioned by operas and symphonies around the world. Grau’s music, which weaves the traditional into a hauntingly original score, is astonishing.

Another noteworthy contributor is Kyoko Terada, a faculty member at the Washington Ballet who also dances in the Aparacio Company. Together, Terada and director Kulikov developed the concept for all the costumes, including those of the mourners and warriors at the beginning.

Salvador was first conceived in 2004 when Aparacio and Kulikov—who met six years earlier studying flamenco in Baltimore—saw an exhibition of photographs of the war in El Salvador and decided that they wanted to create a dance in memory of the war’s victims.

The idea sat on a back burner until earlier this year, when Aparacio received one of Spain’s greatest honors—the Cross of the Order of Civil Merit—for his contribution to flamenco.

The medal, bestowed by King Felipe VI, was a reminder of a debt unpaid. Salvador is the dancer’s tribute to Flamenco—and a passionate ‘thank you’ for the art that saved his life.

GALA’s Fuego Flamenco continues on November 10, 2016, when Francisco Hidalgo and his company take the stage with the Washington, DC premiere of The Silences of the Dance.

Running Time: 90 minutes, with one intermission.

Salvador, a world premiere from Flamenco Aparicio Dance Company, played for three performances on November 4, 5 and 6, 2016 as part of the 12th Annual Fuego Flamenco Festival at GALA Hispanic Theatre – 3333 14th Street, NW, in Washington, DC. The festival runs through November 13, 2016. For tickets, go to the GALA website.

RATING: