As play titles go, Or, is one of the most ungoogleable. It is a search engine dead end. And as an original mashup of past and present, prose and poetry, and performative purposes, Liz Duffy Adams’s Or, is also one of the most unpeggable.

My colleague David Siegel, in his rave review, called the production briskly directed by Aaron Posner now playing at Round House Theatre “the embodiment of literate theater performed by a top-notch cast.” I completely concur—and the provocative script has got me thinking.

Or, is kind of a comedy, in the manner of the Restoration, the era evoked in the play. As such it’s got lots of laughs. But Or, is also something else. Something quite rad. It’s a fusion of feminism and farce as silly and serious as can be.

Or, (the comma in the title is intentional) is the third theatrically adventurous play I’ve enjoyed at Round House that has tucked inside it some fierce feminist consciousness.

Of NSFW by Lucy Kirkwood, for instance, I wrote:

In NSFW Kirkwood skewers the way men’s and women’s consumer lifestyle magazines aggravate and ameliorate their target audiences’ insecurities. And in so doing NSFW pokes a spot-on critique at the entire culture’s commodification of gender anxiety.

Of Rapture, Blister, Burn by Gina Gionfriddo, I wrote:

Given how much feminist theorizing is packed into Gionfriddo’s script—some of it densely, abstrusely academic—one might have supposed that eyes would glaze over. But no, the flurry of feminist ideas in the show played like piquant catnip to a herd of felines (among whom were not a few toms; the audience included many couples who appeared to be on a date). And these weren’t just garden-variety feminist ideas (like: women ought to have choices, it’s hard to have it all, that sort of thing). Sure, there was a lot of such duh, easy-on-the-ears opining. Yet this firebrand of a script also had a thick load of gritty stuff about pornography, a topic that typically makes its appearance in the performing arts salaciously and panderingly. But analytically and critically? Not so much.

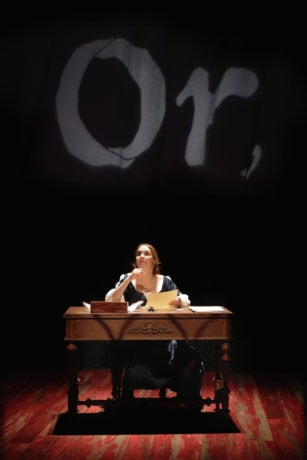

The main character in Or, is the 17th-century playwright Aphra Behn (an entrancing Holly Twyford), who was one of the first women to earn a living from writing. After a somewhat slow takeoff on a long runway of a prologue, Or, lifts aloft on the premise of a hugely feminist joke: Aphra is on deadline to deliver a playscript by the next morning, but she keeps being sidetracked by her lovers (two men and a woman), who keep dropping in on the lodgings that she rented to be (in Virginia Woolf’s famous phrase) a room of her own. Instead, in Adams’s wittily sexy conceit, the place is a pied-à-terre for Aphra’s polyamory. All of which is so much fun to watch play out—passionate kisses, fast costume changes, French-farce door slamming—that it’s easy to lose track of the question that’s really driving Aphra: Will she finish?

In the opus sense, not the big-O one.

Aphra’s feminist convictions about financial independence are set forth early on in a scene with Charles II of England (an impressive Gregory Linington), who has made amorous advances toward her and whose kiss has evidently aroused her.

I am not a professional mistress. I have greater ambitions…. I’m no kind of whore, the kind that marries or the other kind. I’ll earn my own bread or go hungry.

(They kiss again)

Very nice. But a kiss won’t transform me into a mistress nor you into a theatrical contract.

Later Aphra explains for Charles even more explicitly her determination not to depend on a man:

The greatest danger for a woman, let me tell you, plague and fire and war in one, is all-consuming love for a man. As a nation under a tyrant, so a woman in love: all freedom lost for the sake of a specious security that only lasts as long as a sunny day in England; that is, as long as a man loves or a tyrant pleases to be kind.

Throughout Or, Adams cleverly layers a 1960s sexual-revolution vibe over 1660s societal values, but Aphra’s views on mutually volitional sex would have been anomalous in either era’s cock o’ the walk ethos. Aphra spells this out in a scene with the celebrated actor Nell Gwynne (a delightful Erin Weaver), who here is one of Aphra’s paramours.

APHRA: Nature endowed us with a glorious gift for pleasure and nothing is more natural than to take all honest advantage of it.

NELL: And by honest you mean?

APHRA: Willing. The only sensual sin is to take what isn’t freely given. If I am lucky enough to attract the true affection of a lovely man or woman, and if together we can increase the sum total of happiness in the world for even an hour, I consider that an act of virtue, not vice.

Adams gives Aphra and Nell not only a passionate attraction to each other but also a similarly feminist take on the sexual politics of marriage. Comparing it to prostitution, Nell says, “What’s the difference, except you’re selling yourself to just one man. No way around it, to be a woman is to be a whore…”

In perhaps the most nervy instance of radical feminism to appear in Adams script, Aphra and Nell articulate differing views on penis-in-vagina sex. Speaking confidentially to Nell, Aphra says of her lover (and patron) Charles:

Well, to be blunt, I don’t let him fuck me. We exchange every other pleasure but that.

NELL: Why not?

APHRA: … I’ve never really cared that much about that part; it’s all the rest that does it for me.

NELL: I love it, I could do it for hours. Did you see my Cleopatra last season? “O happy horse, to bear the weight of Antony!” I love that line, I know just what she means.

In a unique twist on the feminist “can women have it all?” trope, Adams frames the work-versus-love dilemma specifically from the point of view of a woman writer. And if the play can be said to have a message for women today, it is in this telling exchange between Aphra her ex-lover William (Linington again).

WILLIAM: You don’t love me anymore, you said so.

APHRA: It’s not quite that simple. I never did know how to stop loving, I only know how not to let it stop me.

If Or, is evidence of a pattern in Round House programing—plays by women with feminist core convictions not needing the Women’s Voices Theatre Festival in order to be produced—I’m all for it. And the reason for my unqualified affirmation goes beyond this particular play and this particular writer. Because if professional theater makes room for the voices of the marginalized but does not make room for the most radically liberationist among them, it has not actually made room for any of them.