Sovereignty, the long-heralded new play by Mary Kathryn Nagle – a member of the Cherokee Nation and one of barely a dozen Native American playwrights writing today – has arrived.

Inspired by a Supreme Court case that was heard just two years ago, the play, now in its world premiere at Arena Stage, is one of the highlights of this year’s Women’s Voices Festival. It is superbly directed by Molly Smith, Arena’s artistic director for the last 20 years.

The play, which alternates between the 1830s and today, documents the failure of the US Government to honor its treaties with the Native American population, using the playwright’s own tribe—the Cherokee—to illustrate the fight for self-rule.

Much of the contemporary part of the play relates to a Supreme Court case that was tried in 2016 and that involved the sexual abuse of a child by an outsider on a reservation.

As befits a play about criminal acts, both the theft of Indian lands under Andrew Jackson and the abuse of women so prevalent today, there are plenty of villains and heroes.

Chief among the villains is the newly-elected President Jackson. Joseph Carlson does a star turn as the morally bankrupt leader, a deal-maker and crook who shrugs off promises and changes his mind whenever it suits his pocket, and his modern-day counterpart, a cop named Ben, who turns out to be as brutal as he is venal.

On the other side, fighting for justice, are the heroes. Their leader is Sarah Ridge Polson. Kyla Garcia delivers a lyrical and passionate performance as the young Cherokee lawyer who returns to the reservation, determined to fight for the tribe and for the implementation of the Violence Against Women Act in the United States Supreme Court.

Sarah bears a superficial resemblance to the playwright, who—apart from being an accomplished writer—is a practicing lawyer who specializes in tribal rights and domestic violence on Indian lands. The fictional Sarah, like Nagle, is a direct descendant of John Ridge, the tribal leader whose decisions, nearly two centuries ago, set the plot in motion and form the heart of the play.

Dorea Schmidt is radiant as the 19th century Sarah. She is a schoolmaster’s daughter who gives up her comfortable life in Connecticut to marry John Ridge and become part of the Cherokee tribe.

The Ridges—father and son in the 1830s—are the much-maligned leaders who supposedly sold out the tribe when the father, dubbed “Major” Ridge by President Jackson, signed a treaty, giving up their land in the state of Georgia and resettling in Oklahoma.

As Major Ridge, Andrew Roa portrays a proud warrior and a fine statesman, who—faced with the choice of genocide or resettlement—chooses the latter.

Roa, who is one of four Native American actors in the cast, also plays the Major’s descendant. Despite his outcast status, he continues to sport an elegant braid. (The wigs are courtesy of Jon Aitchison.) Having returned to the reservation to babysit for his grandson, the curmudgeonly exile begins reciting tales of his people in his native tongue. The transition is lovely to behold.

The role of John Ridge, the Major’s son and ultimate leader of the ousted tribe, is played to perfection by Kalani Queypo. A member of SAG-AFTRA’s National Native American Committee, Queypo is also connected to the Native Voices Theater at the Autry Museum.

Rounding out the Ridge clan is Jake Hart. He provides a solid performance as the brother of John in the past, where he explains the benefits of accepting Christianity, and Sarah in the present.

The leader of the anti-Ridge group is John Ross. Played persuasively by Jake Waid, he argues against the treaty in the 19th century and in favor of it in the present. He is Sarah’s boss on the litigation team. (The real John Ross provided recordings of the Cherokee language which are reproduced in the play.)

Michael Glenn is Samuel Worcester, the decent white man who ends up in prison for trying to help the Cherokee, and Mitch, the equally decent lawyer with ties to both the Native Americans and the whites who hang out at the local casino. Observing it all, giving voice and reason to the sometimes confusing events, is Todd Scofield. He is an excellent one-man-Greek-chorus.

Backing up all the performers is an outstanding design and production team. Ken MacDonald’s set is ingenious. A long wooden chest is flanked by panels that descend from the ceiling and a couch that ascends from the floor, allowing the single stage to serve as everything from a humble residence on the reservation to an office and from a schoolmaster’s house to the White House.

An abstract design, reflecting Cherokee culture, is projected onto the backdrop as well as the floor. The design, suggesting sheaths of wheat or corn beneath a rising sun, is adapted by Mark Holthusen, who uses projections to depict different locations, including the Supreme Court.

The lighting, designed by Robert Wierzel, alternates between stark white, bright colors and somber shades. It’s all in perfect tandem with the projections and sound, created by Ed Littlefield, a composer and percussionist who merges Native American drum beats and chants with contemporary music and jazz.

Vocal coach Zack Campion has done an astonishing job training the actors to adopt the inflections of the Cherokee language.

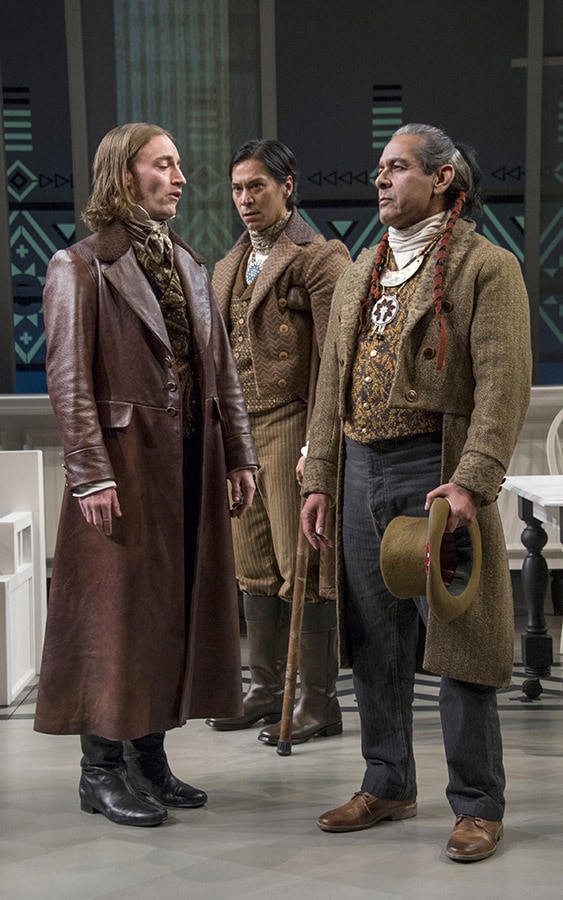

There are wonderful cut-away suits—created by costume designer Linda Cho—for the Cherokee men when they pay their first formal visit to President Jackson. Cho has also designed costumes for the two Sarahs that illustrate the changes they experience when they move from the frivolity of the Euro-American world to the stern formality of the Cherokee.

Sovereignty, for all its wonders, has its drawbacks. The alternation of past and present is initially confusing. It takes a while to figure out who’s who, especially when so many of the actors play double roles. But the shock quickly dissolves into a realm in which past and present co-exist.

This is a very basic concept in Native American culture. And eventually, thanks to the extraordinary direction of Molly Smith and the staging by Susan R. White and Trevor A. Riley, past and present actually merge.

One of the most magical moments in the play occurs when both Sarahs appear simultaneously. The sight of these two women—nearly two centuries apart but holding their babies and acknowledging their link to each other—sent a shiver down my spine.

Sovereignty is an issue play. The issue is the rape of Indian women and the inability of the tribe to prosecute the rapists if they are not members of the tribe. As my colleague Elizabeth Ballou reported here before the play opened, this is theater that aims to “teach as it entertains.”

That’s a tall order. Both the detailed history behind the treaties and the legal arguments—which are literally read aloud from the law briefs–occasionally hold up the story.

Despite its weightiness, Sovereignty is, I believe, a play worth seeing and applauding. There are scenes that evoke laughter as well as shock. And whatever its drawbacks, they are certainly outweighed by this production and the extraordinary performances in it.

Running Time: Two hours including one intermission.

Sovereignty plays through February 18, 2018, at Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater – 1101 Sixth Street SW, in Washington, D.C. For tickets call (202) 488-3300 or go online.