The musical The Scottsboro Boys tells a true story of heinous injustice driven by race hate, and the theatrical form is a minstrel show—bouyant upbeat dancing, rousing melodic singing, and buffoonish caricature, all ironically in service of a historical narrative that is utterly tragic: Nine young black men imprisoned for years, their lives ruined, because in 1931 in Alabama they were falsely accused of raping two young white women and then found guilty over and over again by white juries.

The cast members, all but one, are black. The show’s creators (John Kander and Fred Ebb, music and lyrics; David Thompson, book; Susan Stroman, original direction and choreography) are all white. Many other musicals have had black talent onstage and white creatives off—Porgy and Bess and Dreamgirls come to mind. But in the current context of heightened consciousness about whose stories get to be told on stage by whom, and given the politically charged source material, a question might fairly be asked: Were the creators of The Scottsboro Boys whitesplaining?

Read David Siegel’s DC Theater Arts review

The collaborators did not set out to tell a #BlackLivesMatter story. They began in 2002 looking for a project to work on together and casting about for a famous American trial on which to base a musical. The case of the Scottsboro Boys had popped up in their research, and they went with it. Then they decided to tell the story as a minstrel show. It was an audacious choice because the minstrel-show form in Broadway musical theater had heretofore only perpetuated racist stereotypes. Book Writer Thompson explained the collaborators’ intention this way:

We are going to entertain you, and you are going to have fun, but at the same time we’re going to lead you to a place that is very dangerous and controversial, and what you take out of this, where you get, you’re going to have to sort out yourself, but in the meantime we’re going to entertain you.

The show’s structure deliberately juxtaposes its “let us entertain you” musical numbers (which are plentiful and wonderful) with its dramatic focus on “the truth.” At the beginning, a white emcee called the Interlocutor (a genial Christopher Bloch) sets up a “Minstrel March” number featuring the company in a cartoony cakewalk:

Sit back now

Relax and get comf’table

Sad thoughts out of sightHey hey, say hello

To the minstrel men

Here to entertain you

Tonight!

The “you” in that lyric is presumptively white people; in fact, the whole opening number is a promise to white audiences that their comfort zone will be respected.

The Interlocutor then promises the singing and dancing minstrel men playing the Scottsboro Boys:

INTERLOCUTOR: We’re telling your story boys! Just like we always do!

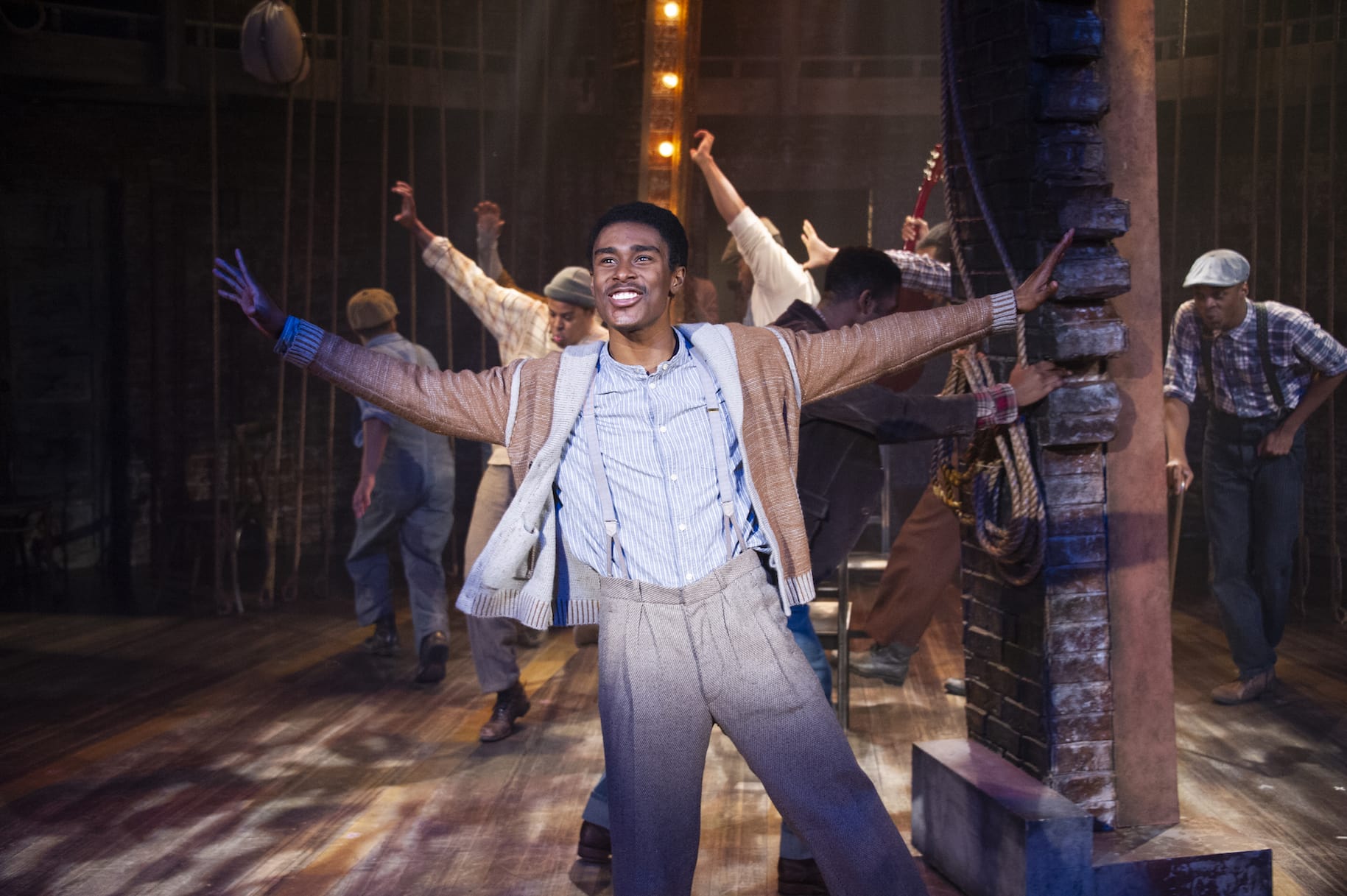

But he is interrupted by Haywood Patterson (a charismatic Lamont Walker II):

HAYWOOD PATTERSON: Mr. Interlocutor, this time can we tell it like it really happened? This time can we tell the truth?

To which the Interlocutor says “of course!” then cracks a change-the-subject joke in cahoots with two stock characters from minstrel shows: Mr. Bones and Mr. Tambo (played with grinning exuberance by Stephen Scott Wormley and Chaz Alexander Coffin).

Thereafter the material—the book, lyrics, and music—continues to contrast the Scottsboro Boys’ calamitous story with the incongruous musical form in which their story is told.

The discrepancy between that story and that form sets up a singular tension that audiences can now experience for themselves at Signature Theatre. The show was designed to walk a fine line between enjoyable send-up and too-horrible-to-absorb history, and in this powerful, top-notch production it does. Director Joe Calarco, Choreographer Jared Grimes, and Musical Director Brian P. Whitted give every wrenching and diverting moment its due, to overwhelmingly moving effect.

Ultimately the musical subverts its minstrel show form and lets the Scottsboro Boys take it over. But the wheels of justice don’t just turn slowly, they grind the boys into the ground. In a later scene, the Interlocutor attempts to reassure them in song:

INTERLOCUTOR: IT’S GONNA TAKE TIME

WE’LL PUT THINGS TO RIGHT

BUT NOT OVERNIGHT

And Haywood interrupts again:

HAYWOOD:

Wait? How can I wait? I’ve done nothing but wait. Thinking this day, next day, something gonna change. Hoping. But what good is hoping when the same high minded people keep telling the same low minded lies.

As I watched the exceptional actor/singer/dancers onstage, I began to realize a layer even more profound than the material, something that transpires in the performers themselves: astounding moments of emotional truth that shine through when the musical interrupts its entertainment agenda and lets the characters have their say.

The first clue one gets to this layer is The Lady. She appears in a prolog, opening up a miniature theater to reveal the minstrel show inside. From then on she is everpresent, sometimes seated in a front row watching, sometimes onstage expressing sympathy and support for the nine accused, always attentive to their story, never saying a word, never for a second responding to any of the entertainment being trotted out. As played by Felicia Curry, whose eloquence without lines is breathtaking, The Lady is our lens into what’s really going on.

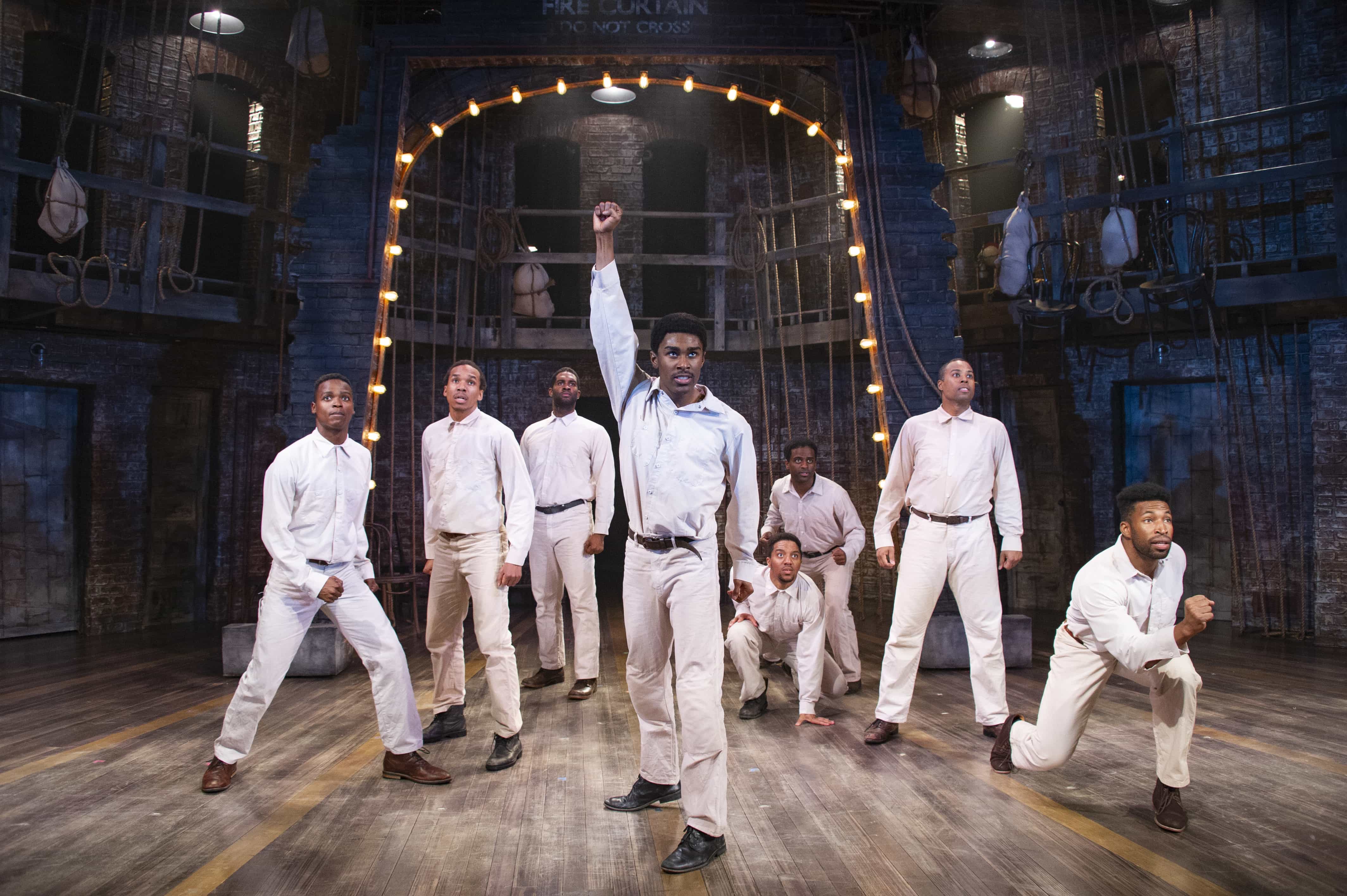

Nine fine actors play the Scottsboro Boys—Jonathan Adriel (as Andy Wright), Malik Akil (Charles Weems), C.K. Edwards (Roy Wright), DeWitt Fleming Jr. (Ozie Powell), Scean Aaron (understudying Andre Hinds as Willie Roberson at the performance I saw), Aramie Payton (Eugene Williams), Darrell Purcell Jr. (Clarence Norris), Lamont Walker II (Haywood Patterson), and Joseph Monroe Webb (Olen Montgomery). Each actor lets us see a distinct individual, one whose character arc ends unhappily, onstage as it did in life. Yet by the end of the show something exhilarating happens, something that transcends both the story and its form: One by one they each break free from the emotional dissonance that all their collective singing and dancing necessarily entailed, brilliant as it was. And in those moments of self-disclosure and self-affirmation, one can witness an ensemble so united there can be no acting award category for it—for it is the shared integrity of nine black men dropping their minstrel masks and finally not acting for the sake of white comfort.

In that color-coded sense, the extraordinary performances in The Scottsboro Boys now at Signature Theatre offer one of DC theater’s most riveting and revealing looks at what it means to be black in America—not only in the 1930s but right now.

And yes, I might have whitesplained that.

Running Time: Two hours, with no intermission.

The Scottsboro Boys runs through July 1, 2018, at Signature Theatre – 4200 Campbell Avenue, in Arlington, VA. For tickets, call (703) 820-9771, or purchase them online.

VIDEOS: