Let’s stop for a moment to consider how much of the grey matter we’ve got upstairs, between those infernal ears, is dedicated to memory. Even as you read this review your mind is stocking up on words from the screen as well as what’s happening around you right now—smells, sounds, baristas, dogs—packing it all away for future use.

And abuse. Funny thing about that. Granted, there’s plenty we will forget (this review being likely at the top of the list), but there’s also the stuff you have no choice but to remember while pretending it never happened.

As the character of Soviet censor Kreplev points out in D. W. Gregory’s gripping new drama Memoirs of a Forgotten Man, receiving its world premiere this month at the Contemporary American Theatre Festival in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, it turns out there’s a whole lot we choose to remember differently. In the interests of marital harmony, in the interests of friendship. And as Kreplev sets the scene for us – portrayed with brilliant intensity by Lee Sellars – he confronts us with a question that is hauntingly prescient: “When survival requires that we pull together for the common good, who would refuse to make accommodation?”

In Memoirs, Gregory has crafted a gem of a play about collective and personal memory which, given the wretched flow of current events, should give everyone pause. We live in an age when the real struggle, online and in print, is for the right to remember or forget facts, events, policies, even our own past.

Our news feeds of choice direct us away from anything that might challenge our sense of ourselves as righteous and good; if our favorite sites don’t mention it, it isn’t happening, and if it isn’t happening in our little world, it doesn’t matter, now, does it? We all make accommodations, we choose to deny what we remember, and refuse to even learn what we desperately need to know.

Based on an actual case study from Russia’s Communist era, clinical psychologist A. R. Luria’s The Mind of a Mnemonist, D. W. Gregory takes us into the dark heart of the Soviet Union under its “Comrade” Chairman, Josef Stalin (Note: this was a totalitarian dictatorship in which everyone was “equal.” Officially, everyone was your comrade – továrich – even if they had the power to crush you). The play focuses on Alexei, a man gifted with synesthesia—a condition which involuntarily identifies words in the mind with colors, tastes, etc.—and who as a result has a virtually limitless memory.

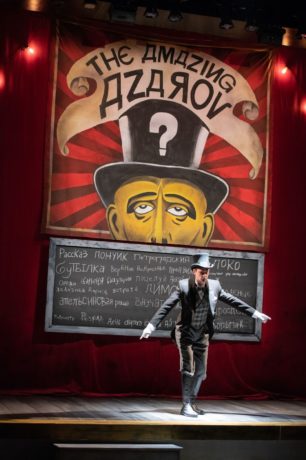

Director Ed Herendeen opens the show with a coup de théâtre—also a nod, perhaps, to Alfred Hitchcock’s espionage thriller 39 Steps. We are greeted by a carnival side-show, in which “The Amazing Azarov” invites guests to write random words (in Cyrillic lettering no less) on a massive chalkboard. Then, after a 2-3 second glance at the results, he turns his back to the board and recites them all with perfect accuracy.

Scenic Designer David M. Barber decks out the curtain at the Frank Center with a massive circus banner featuring the star in top hat and tails. Once the curtain is up, Barber takes us to the bare-bones furnishings of censor Kreplev’s office, with a humble Soviet apartment on a split-level stage, skillfully and strategically lit by D. M. Wood.

Among the many feats of this brilliant production is David McElwee’s turn as the mnemonist Alexei, memorizing everything thrown his way – random words, number sequences, and repeating them backward and forward with the ease of ordering a pot of tea. (Yes, actors memorize lines, but not stuff like this. This actor’s mind boggles to think of it.)

But Alexei’s gift is also his burden because it turns out that people with this condition struggle. It’s difficult for them to develop critical modes of thought that enable normal folks to survive.

Memoirs of a Forgotten Man flashes back and forth between 1950’s Moscow and 1930’s Leningrad (a city of many names, but now known once again as St. Petersburg). The dates are precise, and for a reason: the late 1930’s marked the beginning of Stalin’s show trials, with a long parade of officials forced to publicly confess crimes they never committed, immediately prior to their execution.

Once disposed of, it was as if these officials had never existed. Their names were stricken from the books, and all images of their faces in official photographs were scrubbed away with a brutal efficiency documented in David King’s sobering study, The Commissar Vanishes.

Alexei comes to the attention of psychologist Natalya, who interviews him in the years immediately prior to Stalin’s purges. A victim of the purges herself, after Stalin’s death she tries to resume her career, piecing together her notes on Alexei’s condition to publish them and re-establish her credentials.

She is a survivor, but one who has had to make tremendous sacrifices to make it. The psychological intensity of her interview with Kreplev—in an empty office building, with nobody else around – is a reminder of how fragile her freedom was. Joey Parsons’ interpretation of Natalya is memorable for its resolve tempered by discretion, her awareness that every word, every nuance of her delivery, could land her back in trouble.

As Kreplev mines Natalya’s memory, we see flashbacks to the boy Alexei growing up in an increasingly agitated home in the provinces, with his big brother Vasily who decides to join the Bolshevik Revolution. Alexei meets Natalya after his family has moved to Leningrad; we see his cramped family life in an apartment where a nosy neighbor, Madame Demidova, waits to pounce at the first sign of dissent. (Another fascinating choice here is to have Parsons double as Demidova through a quick costume change managed on-stage in front of the audience. It was a nice, Brechtian touch.) And what, I ask you, could be more subversive than a perfect memory?

What is fascinating here is to see how D. W. Gregory weaves Kreplev’s questions in and out of Alexei and Natalya’s story. Is he asking because he hasn’t read her manuscript yet, or because he has? And if he has, why ask again? Even as we are discovering Alexei, we are discovering other secrets along the way, as the focus shifts with great speed among the three main characters.

The denouement to Gregory’s play—which must be seen to be appreciated—is heart-breaking. But given the ways in which Soviet history crushed its victims, it is impossible to see how it could have turned out differently. It’s a testament to Gregory’s skill that she is able to construct an ending that is as perfect as it is frayed and impossible to mend.

Looming over this production, from one scene to the next, is a figure peering through the panes of an upstage window—Josef Stalin, whose image appears in part at first, but then in full. At the close of Memoirs, there is a final montage of modern dictators, projected upstage so that they’re peering through the glass at all of us—dictators past, present, and (potentially) future. Because it’s not just Alexei’s story, it’s about all of us.

When you come to see the show – not if, but when – I urge you to go through the Play Notes and review some of the dates and personalities of the early Soviet period. To do a historically accurate play, you have to strike a balance between dramatic action and exposition. Too much exposition and it collapses into a lecture. Too little and it becomes vague, with nuances that are hard to catch in one sitting.

To fully appreciate Gregory’s work, the context is everything, and there is one more detail that becomes vitally important as the play progresses: Alexei and Natalya meet in Leningrad in the late 1930’s, a city which in a few short years would be utterly destroyed during a Nazi siege that left few buildings—and few citizens—standing.

Natalya confronts Kreplev in 1950’s Moscow during a brief thaw in government-sanctioned brutality that came after Stalin’s death. Under the leadership of Nikita Khrushchev, there was a rare opportunity for the awkward, halting rehabilitation of some of the purge’s survivors (a viewing of Armando Iannucci’s dark, satiric film The Death of Stalin might help here). But Khrushchev had his own cruel streak—this is the same man who crushed the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and built the Berlin Wall. Before long, the lights were switched off again.

Here’s hoping we manage to keep the lights on here, and for some time to come.

Running Time: 100 minutes, with one intermission.

Memoirs of a Forgotten Man runs through July 29, 2018, at the Frank Center Stage at Shepherd University – 260 University Drive, in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. For tickets, call 800-999-CATF (2283), or 304-876-3473, or purchase them online.