By Norman Yeung

That Theory has gained urgency and relevance since I wrote the first draft in 2009 is uncanny and alarming. Over ten years of innumerable workshops, readings, and productions, the challenge of revising this story rife with internet vitriol wasn’t updating a laptop to an iPad, or a DVD-R to a USB stick, or even #YOLO to… whatever nineteen-year-olds say nowadays. I think “OK Boomer” is currently fire. No, the toughest challenge was navigating a socio-politico-cultural environment that was changing faster than our climate; so fast, that around the time I started writing this play, freedom of speech was a liberal value, and somewhere along the way, it became conservative. To keep my film-professor protagonist Isabelle as progressive as she professes to be, I had to revise the script like a boat riding atop churning political waves, calibrating her moral compass and rerouting leftward in a circle that meets rightward, and ultimately landing on the shores of Irony in the nation of Hypocrisy. I’m being metaphorical, obviously—I’m not referring to Canada or the United States, although those two nations figure prominently in the evolution of Theory. Obviously.

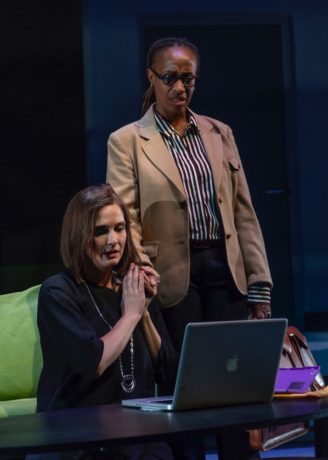

Isabelle creates an unmoderated discussion board for her film theory students to keep talking and learning from each other beyond the lecture hall. Her liberalism gets dismantled when an anonymous student posts increasingly offensive and dangerous material, taunting her to shut them down. My writing of Isabelle grew her from a champion of free speech, to free thought, to giving voice to the voiceless. Her progressiveness became more complex as political positions became more complicated, and liberals were increasingly fighting amongst themselves. Her complexity is very human, like my friend who advocates freedom of speech as much as she does Bernie Sanders and AOC. The evolution of Isabelle and Theory required me to use friends and colleagues as reference points as politics changed. I needed to be guided not by politicians, but by humans. One guide gave me the most consequential advice, sparking the evolution of Isabelle’s wife, Lee.

Lee was originally a white dude. He was Isabelle’s boyfriend and played a minor role in terms of plot and theme. Many of the dynamics and tensions within intersectionality were absent in this early script. In 2013, my dramaturge, the playwright Shirley Barrie, said to me, “Instead of Isabelle merely professing progressiveness, how about she lives progressively? What if she were married to a woman?” I said yes.

Making Lee a woman of color required almost no thought from me. My automatic choice is to make a colorful cast. And because explosive debates over the film Birth of a Nation were crucial to the story, the choice was laid bare before me: Lee would be a Black woman, and Theory would be a new play.

At one workshop in 2018, leading up to the professional premiere at Tarragon Theatre in Toronto, Audrey Dwyer, who was playing Lee, had concerns. Audrey had already played Lee in various presentations, but this current draft dove particularly deep into race relations. And things in the world had changed particularly extremely. Mind the year I stated. In this draft, the element I introduced was that Lee used to be an activist. Audrey’s concern was that if Lee had fought for social justice as a woman of color, how could she be so tolerant of Isabelle’s missteps? She offered to go through the script, page by page, beat by beat, with me and director Esther Jun, to locate moments where Lee’s reactions—or lack thereof—were not congruent with Isabelle’s aggressions, micro and macro. By offering her personal experience and perspective, Audrey was doing so much more than providing accuracy and believability to this relationship—she was giving Lee a soul, and now the heart of the story is Lee awakening Isabelle. And I was re-awakened to the value of listening to an artist I can trust. There are more than a few in Theory’s history.

October 2018, and Theory would have its first professional preview. After the show I was sitting in the house with Tarragon’s artistic director Richard Rose and literary manager Joanna Falck. Things felt grim. “It drags. It’s ten minutes too long,” they said. “These are the cuts you should make,” they said. Massive cuts can feel, to a playwright, like taking a butter knife to your Rubik’s Cube, prying out chunks, and scrambling to put it all back together. Stat. I dreaded what must have felt like slight sadism to the actors, rewriting every night after the remaining six previews until 8:00 AM so they could rehearse new material at 10:00 AM, and perform it that evening. By opening, I had cut ten pages. Richard and Joanna are excellent at what they do, so I took their advice to heart, which is why at that grim first preview my heart was sinking. “Excuse me,” a polite voice chimed in through the grimness. “I don’t mean to interrupt. My name’s Victoria Murray Baatin. I’m here from Mosaic Theater in Washington, DC.” Victoria had nothing but praise and enthusiasm for what Theory was saying, and saw the vision despite a clunky preview. She requested the script and wanted to stay in touch. I turned to Richard and Joanna and etched on my redemptive smile were the words: “I guess my play doesn’t suck.”

Mosaic Theater Company of DC made an offer to produce Theory, and I would have conversations with Victoria and Mosaic’s artistic director Ari Roth about revisions for the DC production. As I expected, I would Americanise—I mean, Americanize—the text, changing “university” to “college” and “mark” to “grade” with the help of dramaturge April Sizemore-Barber. But that’s the easy part. The play’s content is what I wondered about. Over the years, I’ve consulted innumerable professors so I knew I wasn’t off the mark, but now I could consult someone who lends a closer understanding of Isabelle’s world—April is an Assistant Professor of the Practice, Women’s and Gender Studies, at Georgetown University. For this American production in late-2019, was I now off the mark? April didn’t mention any egregious errors. I defer to experts.

In general, I knew Theory would transport well to the United States because Canadians can’t escape American culture and media. Attentive, news junkie Canadians like me are quite knowledgable and familiar with American politics and stuff (it’s okay, reader—we know it’s not reciprocal). I’ve divided my time between Toronto and Los Angeles for years; I’m no stranger to the States. And yet I was anxious about bringing my play to America.

There’s a lot of filth and bigotry in Theory. I’ve sometimes wondered if I’d gone too far with the students’ offensive postings, but then, against better judgement, I read YouTube comments and, yup…real life is way worse. Emboldened by free speech, Theory’s mysterious student injects racial tension into the home of Isabelle and Lee, forcing the couple to confront an issue they’d never had to before: Isabelle’s refusal to silence the student makes her complicit to racism against her wife.

So let’s talk about race. I was born in China and immigrated to Canada when I was a baby. I’ve seen race my entire life. Don’t be fooled by our “politeness”—Canada has a sickening racism problem, especially toward our First Nations people. America has a different narrative, and given its history, demographics, culture, and media might, racism in America seems especially pronounced, violent, and stark. I was anxious about how Theory would resonate not just in America but in DC, where the population is majority African-American and where so many fights for civil rights were fought. I don’t mind if my work offends people’s sensitivities, but if I offend people fundamentally because my work seems irresponsible, reckless, disrespectful…then I’m just being an asshole. And if I seem irresponsible regarding race, then that’s far more problematic than an asshole.

Our first preview in DC. Our audience included many people of color. When an act of racism was about to happen on stage, when a most terrible slur was about to be uttered, I braced myself and hoped the audience would be patient to see it through, that it had context and served the narrative.

One man walked out. Over the next four previews and opening night, with several post-show discussions in between, audience members approached me. They were positive and enthusiastic, some vigorously. Oftentimes they were African-American women. At one talkback, without it being the subject at hand, one woman said she believed Lee and Isabelle’s marriage.

Perhaps I didn’t really need reassurance. After all, Theory has had assured guides its entire existence. Victoria had told me months earlier that she didn’t see any problems with how the play could be received by the DC community. And she certainly wouldn’t allow an irresponsible portrayal of Lee on stage. Nor would Andrea Harris Smith, who is playing Lee. Nor did Audrey, who helped shape Lee to correct my formerly errant writing of the character. I could trust the encouragement and constructive feedback I’d received from LGBTQ+ actors and audience members over the years, whose thoughts helped my revisions. I could have faith in what I learned from collaborating with the directors—every one of them a woman, woman of color, or man of color (once)—who provided an experienced voice to this story about two women fighting institutionalized patriarchy and racism. That Theory remains of-the-moment after ten years is a credit to all the people who advised me along the way. All I had to do was listen.

There is a parallel between a writer and Isabelle. Yes, write whatever you want, say whatever you want. Think however you want. You could even share those words with someone in private. But once you put those words out there—on stage, published, to a lecture hall full of students—there could be consequences. Maybe those consequences were intended, maybe not. But nowadays, for a writer to write whatever they want, including experiences not their own, can be irresponsible. Artists should be allowed to use their imagination, but there are limits to what story they tell; it’s incumbent upon the writer to engage people whose communities are represented in the work, as part of the process of writing. Otherwise, they’re being tantamount to saying, “This is what I believe. I’m right. You’re wrong. I said what I said. You deal with it.” As a character, Isabelle must embody that stubborn, sanctimonious spirit. She must be unbending. Otherwise, she has no journey of awakening. And she does awaken when she listens to Lee. She learns. Isabelle and writers can be good at forcing their ideas on to others, but only when they listen to others—and learn from listening—will they grow. As I’ve evolved Isabelle and Theory over ten years in lockstep with our turbulent socio-politico-cultural attitude, I recall that Isabelle originally wasn’t so obstinate. But neither were we.

Running Time: One hour 35 minutes, with no intermission.

Theory plays through November 17, 2019, at Mosaic Theater Company of DC performing at the Atlas Performing Arts Center in the Lang Theater, 1333 H Street NE, Washington DC. For tickets, call the box office at 202-399-7993 extension 2, or go online.

Norman Yeung works in theater, film, and visual arts. His play Theory had its American premiere at Mosaic Theater Company in Washington, DC, after its world premiere at Tarragon Theatre in Toronto. Theory won the Herman Voaden National Playwriting Prize, was nominated for the Carol Bolt Award, and is being developed as a feature film. Theory will be published by Playwrights Canada Press. He was recently at the Stratford Festival developing his new play Others, a social satire about the shifting power from straight white males to… others. His play Pu-Erh, about language dividing and uniting an immigrant family, received four Dora Award nominations, including Outstanding New Play, and was a Herman Voaden finalist. Other plays and performance pieces include Deirdre Dear (Neil LaBute New Theater Festival, St. Louis), In this moment. (Scotiabank Nuit Blanche), and Black Blood (Tapestry New Opera Showcase, with composer Christiaan Venter). Theory and Ms. Desjardins are available as podcasts (PlayME/CBC). Acting credits include Chimerica (Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre/Canadian Stage), The Kite Runner (Theatre Calgary/Citadel Theatre), Resident Evil: Afterlife (Sony/Screen Gems), Todd and the Book of Pure Evil (SPACE/CTV), and many more. He will be acting at the Stratford Festival in 2020 in Hamlet, Much Ado About Nothing, and Wolf Hall. He holds a BFA in Acting/Theatre from University of British Columbia and a BFA in Film from Ryerson University. Norman is from East Vancouver and lives in Los Angeles and Toronto.