How history will judge us for this administration’s treatment of Central American migrant children, I often wonder. And yet, our record of abuse against “Other” is not partisan, but has accumulated progressively since our nation began, meaning we don’t need to wait for history to offer us perspective.

Why not atone and begin to heal now?

In Series artistic director Timothy Nelson offers us a blueprint for this with his re-imagining of French composer Hector Berlioz’s L’enfance du Christ, “Christ’s childhood” in English. With the historically inclusive Foundry United Methodist Church on 16th Street as the venue, the show is a non-religious respite from the noise of our day and an opportunity to quietly stand together, no matter what we believe or think about each other.

Berlioz’s 1854 oratorio for which he wrote both the text and score, depicts Judean King Herod’s Massacre of the Innocents, the Holy Family’s subsequent flight to Egypt, and finally, after a decade spent wandering, their acceptance by a family of Ishmaelites who are themselves on the periphery of Roman society. It’s about what Nelson calls a work of “radical hospitality.”

Berlioz envisioned his “sacred trilogy” as a triptych which focuses the eye first on the larger middle panel and then draws it left to right, reading the three panels in their entirety. The effect is similar to how a theater or film director will create a mise en scene that locates us at a point in time before allowing flashbacks and future progress.

While it is impossible to begin a score in the middle and jump back and forth, Berlioz focuses our attention throughout by using the story of Christ’s coming, his arrival, and what it means for the future after he’s gone. Christ’s childhood spent homeless with his family is essentially “the middle panel” of the triptych. It’s where the long division is done on what it means to be “home” and why or why not others should be welcome there. Whereas the nativity story is central to Christianity, Berlioz’s setting of Christ’s childhood – essentially the “middle” years of Christ’s entire 33-year-life story – is more historical than liturgical. This makes the work approachable by anyone, regardless of religion or lack of it.

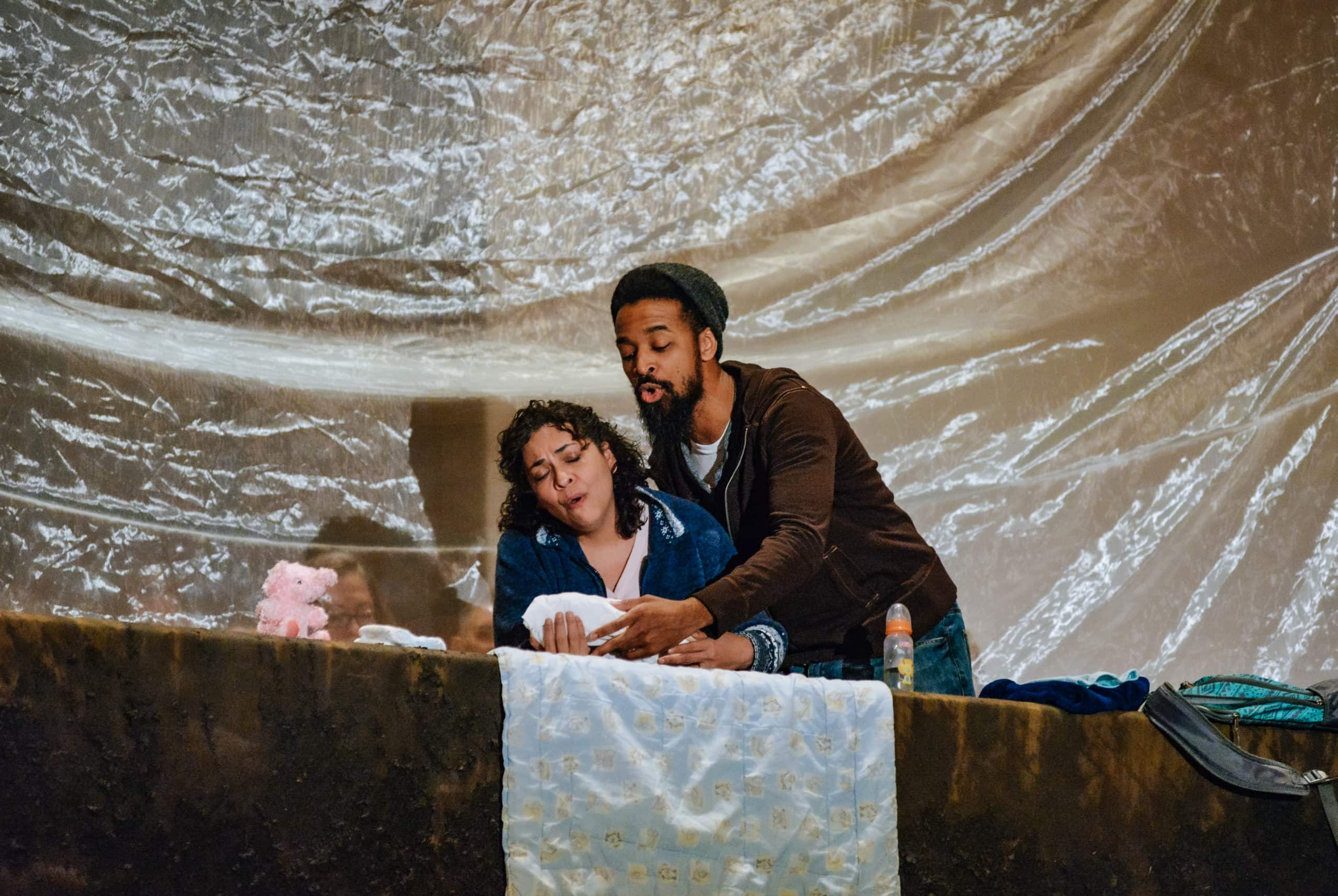

Although current events are clearly reflected in this production, as the centurions wear ICE vests while leading prisoners to a holding area, Nelson’s interpretation of L’enfance does not directly condemn our current administration. Instead, the same cast member who sings the raging and paranoid Herod who orders the mass murder of male infants is the same cast member to sing the role of the Ishmaelite who welcomes the Holy family into his home. This double casting surprised me and made me think it was Nelson’s intention to show that transformation is possible, even in the most tortured of souls.

Nelson and co-director Steven Scott Mazzola chose to stage the work rather than lose the story’s visual power by having the artists stand and sing. Foundry’s music director, Stanley Thurston, led not only a chamber ensemble and an organist, but six soloists, a vocal quartet, and the Foundry Choir as they moved around the church along with about a dozen audience volunteers who participated in various roles such as immigration agents or natives unwilling to welcome Mary and Joseph.

If all that sounds awkward, it is.

Technically, this production teeters on chaos, but that is also the key to its cathartic effect.

As often happens in the creative process, once we allow the gates to open, the universe rushes in with its archetypal truths, layering our work with unintended synchronicities that lend deeper meaning. This L’enfance is replete with such happy accidents, but the acoustical effect of the church’s architecture stands out in particular.

Thurston told me after the show that prior to rehearsal, no one had known that the church’s unique central dome would turn the production into a symphonic cyclorama, bouncing any big sounds beneath it in all directions. Thurston said he normally leads his choir in the front, behind the pulpit, and so had never experienced this weird phenomenon.

The result was Berlioz’s beautiful yet eerie score resounded everywhere and nowhere. It was not muddy or garbled, and because the singers were mobile, the sound washed through each of us, audience and performers alike, differently, depending upon where we sat or stood. Throughout the performance, audience members looked over their shoulders, above them, to either side of where they sat, trying to make sense of what was happening.

How could this not mirror the fear and panic of refugees unsure of who or what is waiting for them, coming from parts unknown?

The show was well cast, well-sung, and featured excellent ensemble singing. I commend each performer. Why I don’t call them out specifically is because unlike any vocal performance I have ever attended in my decades of doing so, the effect of the dome plus the staging was that the singers did not sing at or to me, but through me. And not just me, but everyone, including the singers themselves. It was not a performance so much as a collective rite. I believe that to critique the individuals rather than focus on the whole would denigrate the totality of what I witnessed.

That said, I do believe it’s worth noting that the chaos was well-contained by Thurston’s calm assurance and technical brilliance. Post-performance, he explained to me that the singers and musicians stayed in time not by listening to their parts, but by strict counting and keeping him in sight as much as possible as they cycled through their roving roles as refugees, prisoners, citizens, and guards. I would wager this is the hardest technical performance this cast and choir will ever sing in their careers. Bravo to them all.

With the exception of the “Shepherd’s Farewell,” Berlioz’s spare, lamenting L’enfance is rarely performed, despite its rich beauty. This alone makes attendance worthwhile, even if it were not staged. The elegant yet non-local sounding chorus at the end was reminiscent of Mozart’s Ave verum corpus, and left more than a few audience members silent and tearful after it concluded. I imagine Berlioz would have been delighted with this production that realizes his aim to create a non-linear musical work that takes us deeper into our personal truths, and that thanks to the dome, it was achieved by happenstance.

Nelson’s L’enfance is a complex, intricate rendering of the original, and yet, is not complicated to understand. It surpasses entertainment and reaches into the realm of public ritual. That it explores something so horrible about our national truth without condemnation and judgment, and allows us a safe space to reflect on how that hurts us all in unique ways, is itself an act of radical hospitality.

L’enfance du Christ, presented by IN Series, performs through December 14, 2019, at Foundry United Methodist Church, 1500 16th Street NW, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets online.

Berlioz’s L’enfance du Christ, with new orchestration by Matthew Lynch, is co-directed by Steven Scott Mazzola and Timothy Nelson with musical direction by Stanley Thurston. Cast includes Ian McEuen as Narrator, Joseph Kaz as Centurion, Elliot Matheny as Polydorus, Kerry Wilkerson as Herod/Father, Elizabeth Mondragon as Mary, and Jarrod Lee as Joseph. The vocal quartet is Teresa Ferrara, Elise Jenkins, Kaz, and Matheny. Costumes by Maria Bissex, set by Yacine Fall and JEFF, lighting by Marianne Meadows, stage management by Manon Cook assisted by Allison Lehman. The performance was sung in English, translated from French by John Bernhoff.

I saw this production. I had some similar reactions, especially with regard to how the music inhabited and expanded in the space. I appreciate what you write about it and the clarity with which you write about it here. I found this production and Stormy Weather thrilling and stimulating. If you havent scene Peter Sellars’s ritualization of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, I strongly suggest you seek it out. It’s another example of staging a traditionally static oratorio so as to engage the audience /congregation in a process of self-examination and transformation.