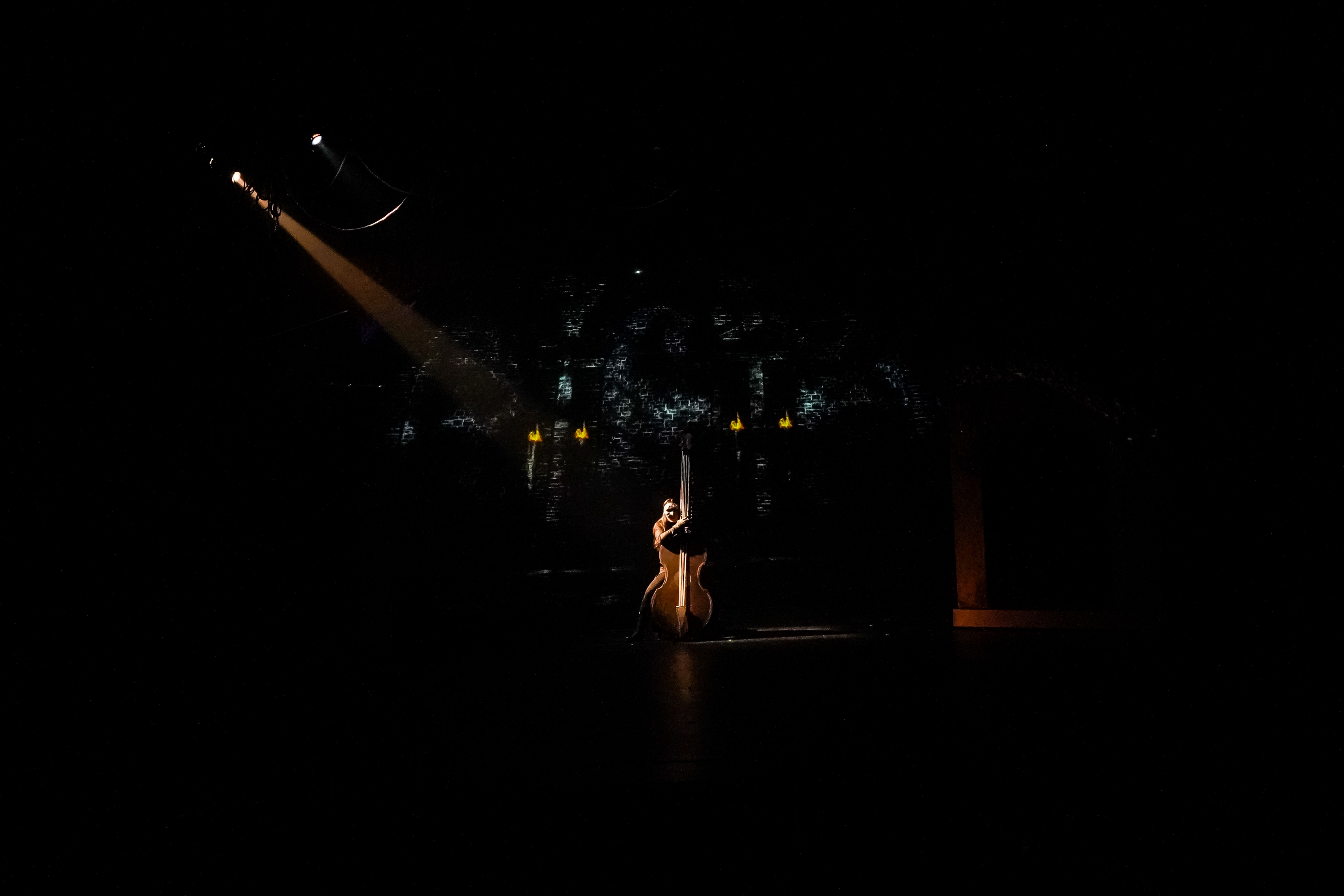

Lights out.

Beat.

Beat.

When the lights go and I’m plunged into darkness, sitting in a theater, my heart always skips a beat, because I know that moment of pause exists to move me—either into the first moment, into intermission, or to that release at the end.

Except this time I don’t know which part of the show we’re in, just that it’s dark, it’s going on a long time, and I’m starting to get scared. Then fear gives way to hurt, as it feels like trust is broken, and I’m questioning my safety.

In the dark.

When asked about what this pandemic has felt like not just as a designer, but as an artist and human being, that is the best way I can begin to describe it. The world changed in an instant, and our industry evaporated overnight. Across the world, people whose work is so closely tied to their heart and identity had that piece of themselves seemingly removed. It was, and is, traumatic.

Theater companies quickly adjusted and there was a surge of digital content, with Zoom readings and performances. Workshops and classes and talks were everywhere. There was a feeling of community coming together to support one another.

Except for designers.

I had made a career of jumping from rooms full of life to the next, constantly surrounded by new people and colleagues that became friends, and friends who became like family. That was what has kept me in the theater for so long: the people. I am not in this industry for the money (shocker), or for awards and accolades (I don’t even really have a Helen Hayes category). I make theater because I love building stories as a collective of artists on both sides of the stage, and sharing them with human beings in a shared room, in a shared moment.

In the early days of this crisis, however, I had never felt more alone.

Our voices, it now seemed, were luxuries instead of necessities. We were not considerations. Our careers of just being names in a program and not faces the average patron could recognize had now meant that we seemed to fade even further away.

This realization led me to embrace something that we as artists seldom ever know: a moment of rest. We were now in a time where you didn’t have to feel bad for not booking the next gig, for not juggling too many projects, for not losing sleep and humble-bragging about your exhaustion—the hustle stopped, all at once, for all of us.

Theater makers all over exercised their greatest talent, one shared across all departments and disciplines: empathy. We directed that emotional intelligence towards ourselves, and towards each other.

“How are you” stopped being a greeting and returned to being a sincere and serious question. Which has led to an examination of what we sacrifice, what we tolerate, and how we operate in this industry because we love what we do.

What became clear to me is that just like the beautiful stages we design, the work culture and environment of the industry was a beautiful facade, but it was not built for proper support of those standing upon it. So many of us are desperate to get back into the room, but we cannot allow desperation to perpetuate a system that abuses artists’ time, health, and emotional well-being.

Theater artists all know the power of the pause, absence, or negative space—this is what we must now remember. I hope we use this time to see all that is unsaid, to investigate the spaces between the lines, and to question what is missing.

So, after a great deal of consideration, I slowly realized that blackout was not intermission. It was the closing moment, without the release of a curtain call. It had to be an ending because from what I’ve learned, we cannot continue this story for another act.

Now is the time for artists to do what we do best: turn imagination into reality. We must imagine a world where creative teams and casts accurately represent the communities and cultures of the artists and audiences they serve. We must imagine new definitions for accessibility. We must imagine structures that empower individual artists instead of silencing them. We must imagine a work environment and schedule that allows artists to be people first, and places value on our emotional and mental well-being and not just physical safety while on stage.

Then we must make all of those realities.

Patrick W. Lord is a DC-based projection and video designer, who has been creating theater across the country for the past ten years. Since returning to the area five years ago, he has designed upwards of 50 local productions. His work has been seen at The Kennedy Center, Shakespeare Theatre Company, Theater Alliance, Synetic Theatre, GALA Hispanic Theatre, Keegan Theatre, 1st Stage, and more. He also recently worked on the video design team to adapt the Broadway show Mean Girls for its first national tour. His work has been nominated across the country, and he is a passionate advocate for Theatre for Young Audiences. He holds an MFA in Projection Design from The University of Texas at Austin. More about him and examples of his work can be found at www.patrickwlord.com.