In a world where our lives are bounded by pandemic restrictions, performance and travel alike have been reduced mostly to private viewings and stay-cations. The situation has spawned experiments to create innovative artistic experiences, a latest one being Okinawa Field Trip, an interactive virtual theater piece from Georgetown University’s Theater & Performance Studies Program conceived to explore themes of environmental issues, U.S.-Japan relationships, social justice, and historical reconciliation. Led by Associate Professor and Playwright/Director Natsu Onoda Power in a student-devised group process, Okinawa Field Trip is a curious study. As a “performance” it raises questions that professional and student artists alike need to wrestle with seriously in attempting cross-cultural work.

A first question is “Who is it for? — Who is the audience?”

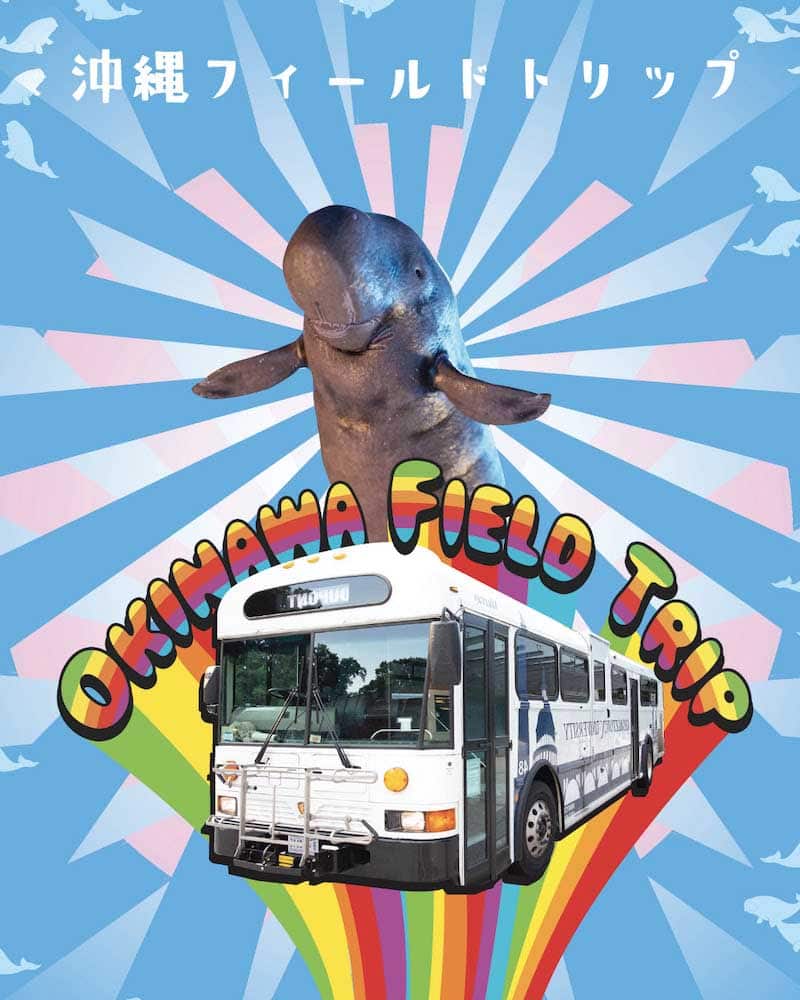

In the opening, Doug E. Dugong, a puppet representing an endangered sea mammal native to parts of the Indo-Pacific, invites us to join him on a “magical bus.” This cheerful, blubbery figure, who greets and wants to engage the audience in songs with lyrics like “Who knows what we’ll see/in the land of possibility/in Okinawa,” leaves no doubt that the show is created for children. It’s learning through entertainment. (Simple language lessons are thrown in and a little about the history of Okinawa.) But scenes grow darker and the material more “adult,” depicting situations of protest and political unrest. There’s even a scene in a bar, with alcohol shots lined up where the “tour” reveals another side of the port city and military-base culture. It throws the audience into a state of confusion, and everyone lapses silent unclear how to engage.

A more satisfying experiment that answers this question is found in the work of another company, BASAbali, which has engaged children all over the island of Bali in the creation of the superhero character Luh Ayu. In both books and recently an animated film, BASAbali tackles some of the same issues as Okinawan Field Trip, including environmental challenges affecting native fauna and flora and the rescuing of an indigenous language and culture. Its targeted audience of children is always kept in mind.

Another question that gets raised is “Who gets to tell the story?”

In recent years, this question has come to dominate the conversation and fuel the culture wars. Cross-cultural experiments are even more subject to criticism.

Power is a powerful local voice and advocate for authentic and respectful narrative. I would welcome her joining a conversation on this topic. For me, there were “cringey” moments throughout the evening.

However, one of the most successful depictions in Okinawa Field Trip is the insertion of a ghost character, an American GI who comes to life as someone stationed at the U.S base in 1969. Here we get a welcome taste of dramatic complexity of character. One could see the young actor had done his homework and selected a role and situation with built-in conflict. The character straddles the worlds of the U.S. military and Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. He is also an African American in what many felt was U.S.-occupied Okinawa while “back home” the Civil Rights Movement had exploded the previous year in riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

There is also a Japanese musician who serves as a local guide and teacher. He has made it his mission to use music and storytelling to rescue the local language of Okinawans of this island long colonized by the Japanese. His participation gave us rare moments of rich authenticity.

This leads me to a final question I had watching this piece: “How to avoid surface skimming culture and instead take a deeper dive and activate an emotional connection at the heart of theater?”

The International Baccalaureate Primary Years Programme (PYP) and other international school models have wrestled with the same challenge for many decades. Leaders in “best practices” call out the pitfalls of annually trotting out what they term as “flags, feasts, and festivals.” Sadly, there were quite a few “flags-and-feasts” gaffes in Doug E. Dugong’s tour. The show even included a pit stop for lunch where local cuisine was extolled and virtually sampled. Meanwhile, the puppet Doug-ee chomped on the manatee-like creature’s preferred sea grass.

Finding mature and challenging source material appropriate to the age group and goals of Georgetown University’s finest might offer some solutions. A couple of books come to mind: Director Sir Peter Hall’s Cities in Civilization about the intersection of civic and cultural histories, and local writer Blair A. Ruble’s fine work, The Muse of Urban Delirium: How the Performing Arts Paradoxically Transformed Conflict-Ridden Cities into Centers of Cultural Innovation. Ruble’s writing on the Japanese city of Osaka and the social-political-economic factors that brought the flourishing of Kabuki theater is particularly strong.

As for performance addressing our environmental crisis, you can bet there will be more companies wading in to save species like the dugong and hopefully move people to action in addressing climate change and humans’ ongoing degradation and disregard for nature. This project could be a step in preparing students for the new field of arts advocacy in the service of the planet.

Running Time: Approximately 90 minutes.

Okinawa Field Trip is available to view live at 7 pm ET April 19 to 22 and April 26 to 29, 2021. Register for free at Eventbrite.

This virtual event serves as the main project in the Georgetown University Theater & Performance Studies Program’s “Seeds of Change: Reimagining the World” season celebrating the Davis Performing Arts Center’s 15th anniversary.