UPDATE: Solas Nua’s Silent will stream on demand July 11 to 18, 2021, in a film adaptation of the Olivier Award–winning and Helen Hayes Award–winning production last seen live in DC two years ago. Written and performed by Pat Kinevane, Silent is the touching and challenging story of homeless McGoldrig, who once had splendid things. But he has lost it all—including his mind. The event is included as a part of Solas Nua’s Summer Theatre Membership. No additional charge is required for Members. Individual tickets for nonmembers are available for $15 online.

Review of Silent at Atlas Performing Arts Center

Originally published March 8, 2019

When we see an unwell homeless person on the street—these days huddled in layers of rags against the cold—we can know nothing of the story of who they are and how they got there. All we can really know is that their story has come to a bad end. Pulling back that shroud of anonymity and ignominy,an utterly transfixing solo performance from Ireland gives us eyes to see how much we can’t.

The work is called Silent, written and performed by Pat Kinevane, who has been touring in it to international acclaim, including London’s prestigious Laurence Olivier Award. The Irish arts group Solas Nua has imported the Fishamble theater production directed by Jim Culleton for a most welcome run in the Lab Theatre II at Atlas.

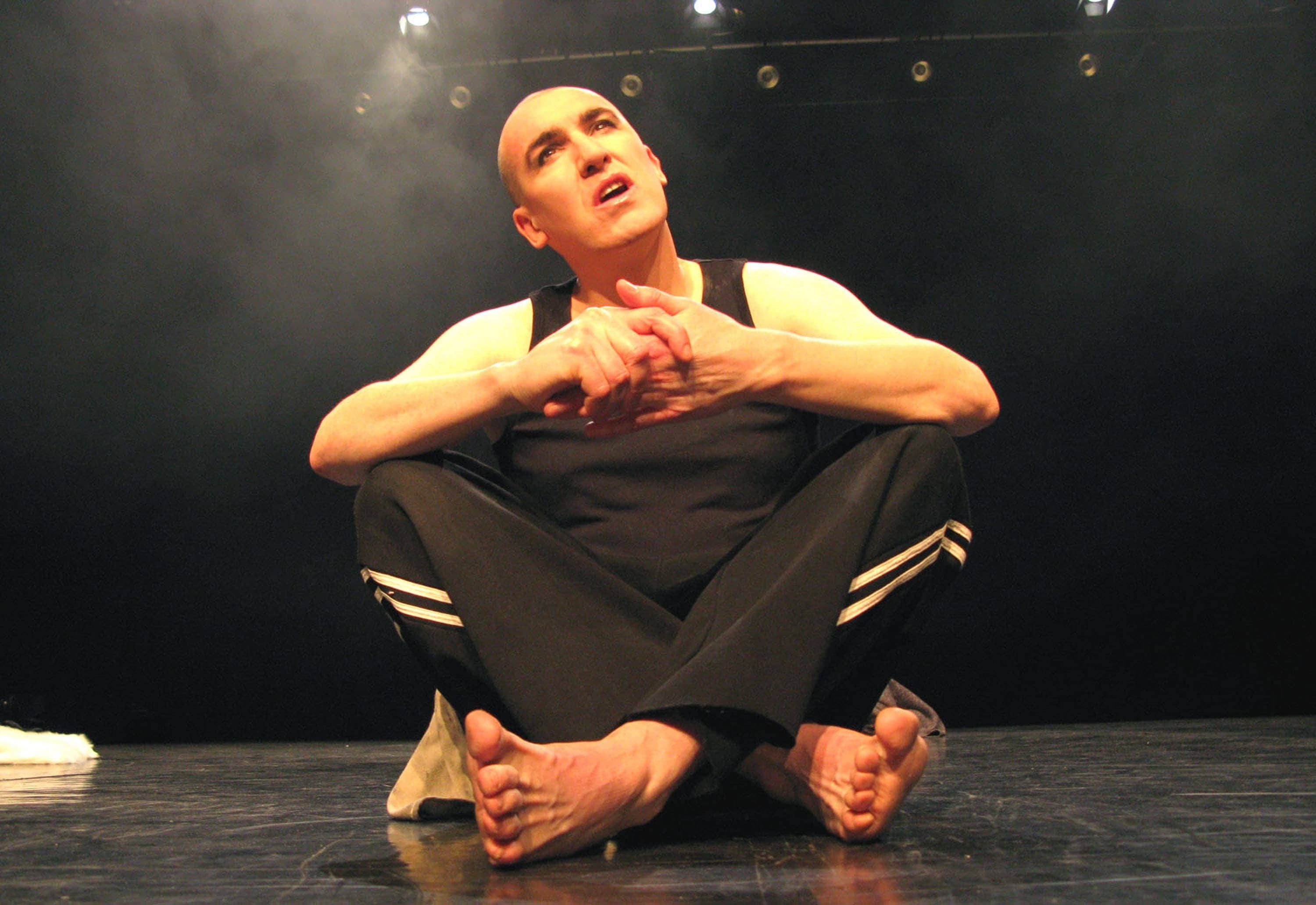

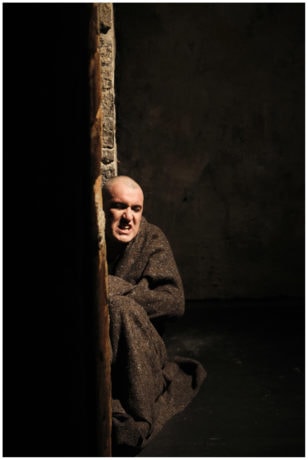

The vast black box is empty but for some scattered props, a bowl to drop change in, a bottle, a garbage bag. There’s a dull roar of road traffic. A figure lies under a brown blanket and slowly stirs. When he emerges, wearing a nondescript black outfit, we behold a mature and sturdy performer who moves with a dancer’s grace, a vamp’s camp, and a meticulous mime’s precision. There is choreography in every gesture, every digit, every blink. Then when at last he speaks—with a vocal versatility that has more tonalities and timbers than could possibly belong to any one person—we are drawn irresistibly into the backstory of a Dubliner down and out.

His name, we learn, is Tino, after Rudolph Valentino, because his mother Nana “lived for silent films.” Besides his parents, who did not treat him well, we meet his gay brother Pierce, his ex-wife Judy, and the son he was cut off from when Judy kicked him out. He once had “splendid things,” he says—a job, a home, a wife—and he has lost them all in an inchoate life on the street drinking cheap merlot and clinically depressed.

Tino’s narrative is grim but not grimly told. It unspools surreally, cinematically, highlighted now and then by silent-film-like scenes in which Kinevane’s delightfully overdramatized self-presentation becomes ever more captivating. Throughout, the light cues are sudden and stark, sometimes single spots piercing the dark from shifting angles, with swelling interludes as of music from old movies. (At one point Kinevane channels Valentino in The Sheik.)

But there is no fourth wall. Kinevane connects with a couple of members of the audience, greets them by first name, banters with them a bit, then continues to speak to them during the show—which has the curious effect of making each one of us feel personally addressed.

There are images and scenes in Tino’s story that burn themselves into one’s brain. He tells of a 40-year-old man in a homeless shelter, for instance, who every night in his sleep would howl “Mamaaaa!” And he does a witty riff on antidepressants that for anyone familiar with the social stigma might briefly seem healing.

Among the moving subplots in Tino’s spiraling story is his relationship with his one-year-older brother, Pierce, who was viciously attacked for being gay (“they murdered him with giggles and sneers”). Tino, who grew up straight, was deeply fond of him. Tino tells a funny flashback of when as boys they shared a bedroom and came upon (no pun intended) their respective stashes of porn—Tino’s called Dirty Slut; Pierce’s, Cockatoo. Kinevane uses the moment to mimic and ridicule the mid-orgasm facial grimaces that photographs in both stashes had in common. Why couldn’t they look happy? he asks. In a show with a lot of laughs, that got one of the largest.

“All he wanted was to be wanted, you know,” Tino says ruefully; “Isn’t that what we all want?” And after his beloved brother was driven to suicide: “Guilt wouldn’t leave me because I should have stood up for him more.”

As performance art and storytelling, Silent is a breathtaking tour de force. As theater with a social conscience, its evocation of the humanity hidden within homelessness is harrowing and heartrending. But maybe most important of all, Silent is a rare and wonderful experience that can remind us who we are when we care.

Credits

Written and performed by Pat Kinevane

Directed by Jim Culleton

Music composed by Denis Clohessy

Stage Managers: Ger Blanch & Aziza Kelly

Assistant Stage Manager: Susan Squires

Costume design by Catherine Condell

Produced by Eva Scanlan

Running Time: About 90 minutes, with no intermission.

Silent plays through March 24, 2019, at Solas Nua performing at the Atlas Performing Arts Center, Lab Theatre II – 1333 H St NE, Washington, DC 20002. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 399-7993 ext 2 or purchase them online.

Solas Nua has arranged a series of post-show discussions after select performances featuring special guests from organizations working to end homelessness in DC. For a full schedule, click here.