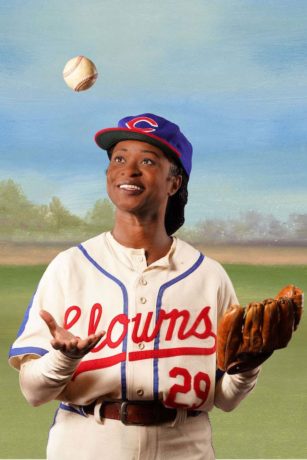

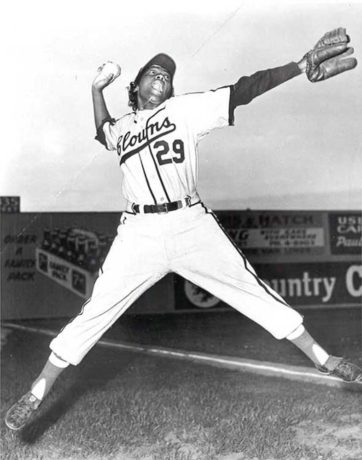

Arena Stage’s first in-person production since the pandemic, Toni Stone featuring Santoya Fields in the title role, is the true-life story of the first woman to play professional baseball in the Negro Leagues making her the first woman to play in a professional men’s league.

There are no women in the Major Leagues today. Toni Stone, an unknown name to most, is the forgotten but resurrected her-story of a woman in baseball, slugging it out against race and gender stereotypes and barreling it up to make dreams come true against the odds.

Call it kismet because the synchronicities between Toni Stone’s and Santoya Fields’s personal journeys seem more than just a coincidence. Fields seems destined to be playing this role. The San Francisco Bay Area was the same yard for both in charting new territories, expanding identities, and throwing a curveball in living proof that “a woman can do many things.”

Toni Stone was scheduled for Arena’s 2020 season, in time to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Negro Leagues, but COVID-19, also at the centennial mark for last century’s pandemic, postponed the show until now.

In conversation with Santoya Fields, we talked about her path from dance to acting and arts advocacy inspired by the mental fortitude of a multi-skilled female athlete she feels honored to portray in Toni Stone. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ramona Harper: Why does Toni Stone’s story need to be told, and what made you want to bring it to life?

Santoya Fields: That’s a great question. Her story needs to be told because it is a powerful part of American history. So many of our greats from the Negro Leagues are forgotten. They are now honored in Cooperstown [Baseball Hall of Fame], and it’s acknowledged as a professional league — but so many statistics and records would be different if they included Negro League baseball. There were many phenomenal players, but Toni in particular competed with the men, and her statistics competed with the men. She had a great lifetime batting average. It’s an amazing story because there are no women on professional baseball teams today. Toni did something at a time when being a Black woman and taking the actions she did was unheard of. It speaks to her character. It speaks to her imagination, her desire to do whatever needed to be done to accomplish this goal.

One of my favorite quotes by her is “A woman has her dreams too,” and playing baseball was her dream. She made that a reality at a time when this country was not ready to acknowledge it. Even when we look back on it now, it’s truly amazing what she accomplished. All of that for me is why I wanted to step into this role.

When I was growing up in Tampa Bay, Florida, I wanted to be a baseball player. We had all the spring training games, and my little sister and I were the only two little Black girls out there watching the Yankees spring training games and going to Rays games. I was first introduced to this play when I was asked to be a reader for the auditions in San Francisco, and at first I thought the character was fictitious because I’d never heard of her. When Pam [MacKinnon, the director] explained who Toni Stone was, my mouth just fell wide open, because I grew up watching baseball, I used to work for a sports network, how did I not know about her? In that moment, I knew I wanted to be a part of this play. I was offered an understudy role in San Francisco and then was contacted to audition for the DC run a year and a half later. It felt synchronistic. I kept remembering that moment when I realized Toni Stone was a real person and I went and I read everything I could about her. I was so sad that I did not have her as a role model growing up, but I am also grateful that I’m able to be apart of bringing her story to young Black girls right now.

You were already a baseball fan, you were already into baseball, but what specifically did you do to prepare for this role?

I was a dancer growing up and so I wasn’t allowed to play sports. I went to a performing arts high school and I was the batgirl, for about a week, on my high school baseball team. When I moved to New York, I joined a recreational softball league. I’ve always wanted to know what it felt like to hit a homerun. But I have very little experience playing the game. The biggest thing for me, going into this role, was getting in shape and getting more into my body. There’s a rhythm to baseball and there’s a rhythm to the movements. So that was first and foremost.

And I’ve tried to embrace Toni’s mental strength. We see generalized archetypes about Black women being strong in an emotional way or a stoic way. Toni was mentally and physically strong. I can’t imagine how she existed in this male-dominated space and it didn’t affect her. It didn’t sway her love for the game.

So many times as Black women in this country, we have objectives that we want to reach but obstacles and barriers force us to go in a completely different direction. Toni was hyper-focused on the game and on her dream. She was able to silence everything going on around her. Imagine what it was like to do that in the fifties. Toni’s mental and physical strength is something I really want to bring to this role and in my own life: that hyper-focused mental strength and the endurance it takes to play the game.

Lydia R. Diamond, the playwright, has written several award-winning plays celebrating female characters. There’s her adaptation of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and her plays based on Lizzie Stranton and Harriet Jacobs. Do you see connections between these characters and Toni’s life story?

You’ve worked professionally in theater and film, but you’re also a teaching artist with the Leap Arts in Education organization in the Bay Area, doing work with underserved communities. What made you take that leap from your initial interest in being a dancer to acting to arts education and activism?

I moved to New York with a scholarship to Alvin Ailey when I was 18. I quickly stepped away from dance because I thought I wanted to be a sports writer. When I was growing up in Florida, I would take my quarter and go to the corner newsstand and buy the St. Petersburg Times just so I could look at the sports section. Growing up my goal was to work for ESPN. I achieved that goal twice, once when I was an intern and years later when I worked in their Creative Works Department. I got to spend a lot of time at the network and experience what it was like to be in the industry. Then I started to feel a shift in myself. I wanted to have a different impact than what I saw behind the scenes.

I started to take acting classes as a way to open up because I was super shy. I didn’t consider acting as a career until years later. My first year acting, I needed a way to make money. A neighbor randomly recommended me for a teaching artist job in the Bronx. I had no experience but I went to the interview anyway because I needed the money. The job was in the neighborhood literally behind Yankee Stadium. I arrived for my interview, and the program director asked if I had any experience. I’m like, “no.” He says, “OK, let’s take you in the room and see what you can do with the kids.” And I tell you, as soon as I walked into the room, I immediately connected with those students and with teaching. I immediately felt like I was in my element. Teaching is one of those things in life that I’ve never needed to learn how to do. I have benefitted from mentors who have provided guidance, but teaching itself came naturally for me.

Acting is not therapy, but it does have the potential to allow individuals to channel trauma into productive outlets. That is what arts therapy is. I see an opportunity in arts education to allow us to speak truth to and heal our students. I believe when we do not speak the truth of our pain, dysfunction develops and that is where children can go off path. As a teaching artist in the Bronx, I was serving kids who faced challenges at school and at home. I created improv games and exercises where we could take characters and real situations from within the community and create art, and sometimes humor, around those experiences. We created a safe space where they could speak their truth and then we dreamed beyond that reality.

In all of my classes, I draw the comparison that we use imagination to become characters, and that students can also use their imagination to become whatever they want in life. I tell students: When I was a little girl, I wanted to work in sports television and I did, and then I wanted to become an actor, and I did. Before I achieved those goals, I first had to see it in my mind and imagination. Imagination is a powerful tool for anyone, but especially in underserved communities, where we don’t always see Toni Stones represented, I didn’t always have images of someone like Kamala Harris growing up, seeing these images is where inspiration develops. And without imagination we limit ourselves to only that which we can see.

Thinking about those underserved communities, what tools can we use to engage them, get them more involved?

Something that I’m learning is racial esteem — because I’m in school as well. Racial esteem is something that is developed when we Black people understand the full journey of our history — from Africa going everywhere that we have now touched the world. There’s an element of our history that is still hidden, elements of history have been changed. What I have found is that in learning the truth about where we come from — specifically the history in Egypt and the impact that we have had on the entire world — we gain esteem for ourselves, for our history, for each other. I know that that sounds very pie in the sky, but in truth, it made a tremendous change for my perspective and how I see the community. I hope to create teaching around racial esteem that will empower the youth — even if there’s still a debate around critical race theory. If we teach racial esteem, if we teach the true history of our people, I think that that could have tremendous impact on underserved communities.

Toni Stone was a trailblazer. She struggled to be accepted in a male-dominated game. What is the message that you most want to convey to the audience about her life that gives relevance for the racial and gender inequities of today?

Black women in sports are highly scrutinized. I mean, Sha’Carri Richardson, Serena Williams, Naomi Osaka, Simone Biles — for these women presenting their true selves is a feat within itself. They face challenges and obstacles, from within our community and from outside of it. Toni’s resilience is something that has impacted me, because what she did in the 1950s was so incredible.

There’s a story in the last chapter of the book [that Toni Stone is based on, Curveball by Martha Ackmann], about Toni in Cooperstown. Before she passed away, the living Negro League players were brought to the Baseball Hall of Fame, as a way to acknowledge that they existed. As someone on the podium was giving a speech, the book describes a little voice in the back that speaks up and says, “I want to say something.” It’s Toni’s voice. She makes herself heard in the space just to say, “I’m glad that we’re being acknowledged. And I just want to say, I’m grateful to be here.” To me that is Toni inserting herself in the room and into the legacy of baseball to say, “I am here, I exist.” That is also what the play is doing. I hope people walk away more fascinated about Toni, and the other women who played in the Negro Leagues, and I hope Toni’s name rings in the minds and the hearts of people who come to see this play. Because her name needs to be heard and people need to know that she existed.

Toni Stone runs September 3 to October 3, 2021, in the Kreeger Theater at Arena Stage, 1101 Sixth Street SW, Washington, DC. Tickets may be purchased online at arenastage.org, by phone at 202-488-3300, or at the Arena Stage sales office Tuesday through Saturday from noon until 6 p.m. For information on savings programs such as pay-your-age tickets, student discounts, Southwest Nights, and hero’s discounts, visit arenastage.org/tickets/savings-programs.

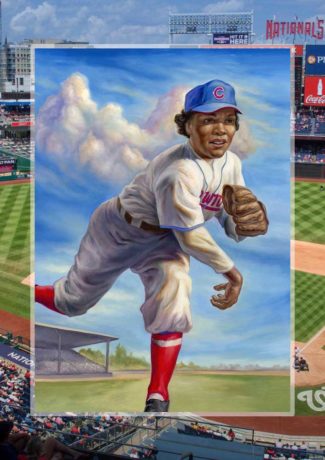

For a special one-night-only event September 26, 2021, Toni Stone will be simulcast to the center field videoboard in Nationals Park ( 1500 South Capitol Street, SE

Washington, DC) for up to 12,000 people to experience. Reservations are free and available online.

Santoya Fields is a teaching artist and actor whose credits include School Girls; or the African Mean Girls Play (Berkeley Repertory Theater); Men on Boats (American Conservatory Theater), Black Odyssey (California Shakespeare Theater) and White (Shotgun Players). For her performance in White, Fields was nominated for two theater awards. Offstage Santoya studies African American Studies at UCLA. She is an advocate for arts and education, and creates workshops and trainings focused on historical cultural awareness, racial esteem, and equality in organizations and classrooms.

This interview was re-edited for clarity August 29, 2021.

SEE ALSO: Arena Stage to roar back with mix of bubbly and soul

i would love to play profeshenel baseball