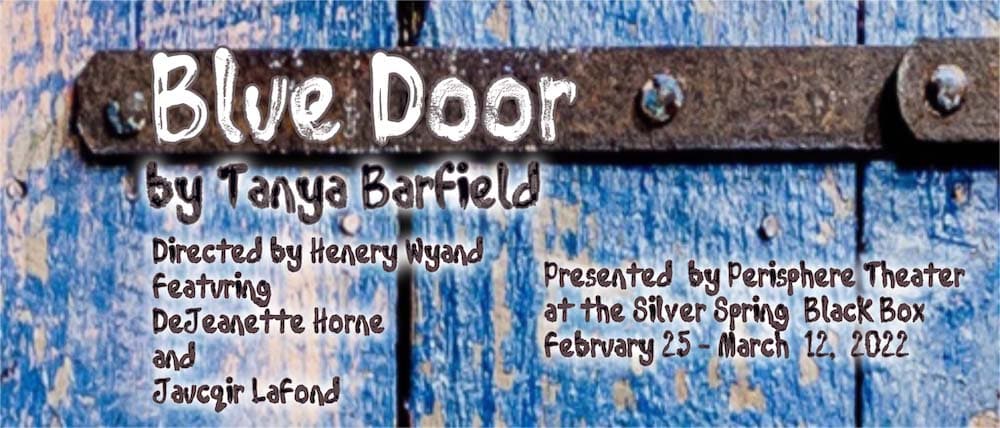

The title of Tanya Barfield’s play Blue Door derives from “a belief in Gullah culture that if you paint your door blue, you keep away the evil spirits,” she has said. Those ghostlike spirits, as she understands them, were “the white slave masters or KKK.” It is a powerfully poetic image for a powerfully poetic play, now running in a beautifully staged and stunningly evocative production directed by Henery Wyand for Perisphere Theater.

At the center of Blue Door is a man named Lewis (a prepossessingly expressive DeJeanette Horne) who lives behind a closed door of another sort, one he uses to keep away from his consciousness the historical fact of being Black — the generational heritage of slavery and the psychic injury of racism. He is fiftyish, a high achiever, a successful professor, a philosopher of mathematics, and he is married to a white woman. She, sensitive to his ambivalence about being Black, has urged him to take part in the 1995 Million Man March in DC, but as the play begins she has left him because he won’t — also because he shirks his share of housework. Bereft and beside himself, Lewis is now in his office trying fitfully to sleep but beset by insomnia and apparitions of his ancestors.

In his waking dream, a cast of deceased characters going back to the 1850s appear — including his great-grandfather Simon, who was born into slavery; his grandfather Jesse, who was freed then lynched; his father Charley, who drank and beat him; and his younger, more militant brother Rex.

All of these spectral figures and more are portrayed with transfixing grace and quicksilver versatility by Jaucqir LaFond, a graduating senior acting major at Howard University whose work first impressed me in a Young Playwrights’ Theater virtual production last March.

In multiple narratives and portrayals, from charming to alarming, LaFond encircles Lewis with the past his mind wants not to know. When we learn, for instance, how Simon sweetly courted Katie, who was owned by the master of a neighboring plantation, LaFond’s Simon comes alive with animated excitement. LaFond’s understated recounting of Jesse’s lynching makes the mental picture all the more horrific. And throughout Blue Door are a capella songs by Barfield, some in English, some in Yoruba, which in LaFond’s lovely voice become haunting pleasures to the ear.

Vivid incidents of indignity abound in Blue Door in both Lewis’s life in the present and his ancestors’ lives in the past. Among them are a familiar scene when Charley in a tux at an all-white professional social gathering is mistaken for a waiter, a historically resonant episode of early voter suppression, and a chilling vignette when 7-year-old Simon is molested by a 15-year-old white male tutor.

Barfield’s poetry in Blue Door is the sort that sends shivers it’s so emotionally precise and profound. Here for instance is a passage from the scorching scene in which Rex excoriates Lewis for his accommodation to “the white gaze” (always looking at himself through the eyes of white people) and his being “afraid to be Black”:

LEWIS: Your mentality, illiterate victim mentality, you call being black. You want me to talk the talk, walk the walk, hang with the homies, gangsta rap my way to the American dream by bitch-slapping our people outta intellectual parity.

REX: Keep it real, Lewy-Sambo. [to the audience:] He a white devil in black skin, my bro. [back to Lewis:] Go on, brother, defame my image…. Tell Whitey ’bout your drunk of a daddy, how you reinvented yourself in yo’ own image, pulled yourself up from your bootstraps, you American dreamer. Tell ’em all ’bout after Malcolm and Martin shot, when I (your blacker bro), spiraled down outta The Movement. Ended up homeless and on crack. Why don’t you tell Whitey how both our mama’s boys (you the good son and me the bad) suffer the same sickness, self-loathing, the silent affliction, a plague of the skin. Both our daddy’s sons suffer the phantom illness called self-hate.

Henery Wyand not only directs with an assured vision but also designed the evocative set— a wood-chip-covered surface in which are buried props and the past — the costumes, and scene-setting sound. The lighting by Adam Mendelson flows in subtle sync with the show’s emotions. And the costumes — classy silk pajamas for Lewis; roughspun henley shirt and suspenders for his unwelcome visitors — are exactly apt.

The eloquence of this fine play is beyond saying. Like the best of dramas, it opens a door to understanding. And the beauty of its staging is indelible.

Running Time: One hour 35 minutes with no intermission.

Blue Door plays to March 12, 2022, presented by Perisphere Theater performing at the Silver Spring Black Box Theatre, 8641 Colesville Rd, Silver Spring, MD. Tickets ($34 regular price, $28 senior, $24 student) are available online.

The Blue Door program is online here.

COVID Safety: Proof of vaccination against COVID-19, including a booster, is required to attend the play. Requests for exemptions must be made at least 48 hours before a performance. Patrons are required to wear masks that provide a full seal over both mouth and nose at all times unless drinking water. For more information about COVID protocols see perispheretheater.com/covid-19-precautions/

SEE ALSO:

‘To tell a Black story by a Black artist’: Henery Wyand on directing ‘Blue Door’ (interview by John Stoltenberg)

CAST

DeJeanette Horne: Lewis

Jaucqir LaFond: Simon/Rex/Jesse

CREATIVE TEAM

Tanya Barfield: Playwright

Henery Wyand: Director/Sound Design/Set Design/Costume Design

Sarah McCarthy: Stage Manager

Kevin O’Connell: Producer, Dramaturg, Props Designer

Adam Mendelson: Lighting Designer

Renata Taylor-Smith: Assistant Lighting Designer

Steven Leshin: Scenic Assistance