Ambiguity. Uncertainty. Absence of any clear, unitary truth. Identities in conflict. Events seen in diverging ways through the lenses of those identities. Perhaps better, as the title of the play suggests, events distorted in the mirrors of a people’s consciousness of who they are and who adjacent “others” are. Such is the world of Anna Deavere Smith’s Fires in the Mirror, now playing at Theater J.

The groups Smith examines are Blacks (many of Caribbean origin) and Hasidic Jews (the Chabad-Lubavitch branch), living in close proximity in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn but in different cultural worlds, with tension not far under the surface. In August 1991, a car driven by a bodyguard to the leader of the Hasidic community ran a red light, causing an accident that killed a 7-year-old Black boy on the sidewalk, Gavin Cato. A few hours later, a Hasidic man, Yankel Rosenbaum, was attacked by a group of young Black people, later dying of his injuries. Four days of violence followed.

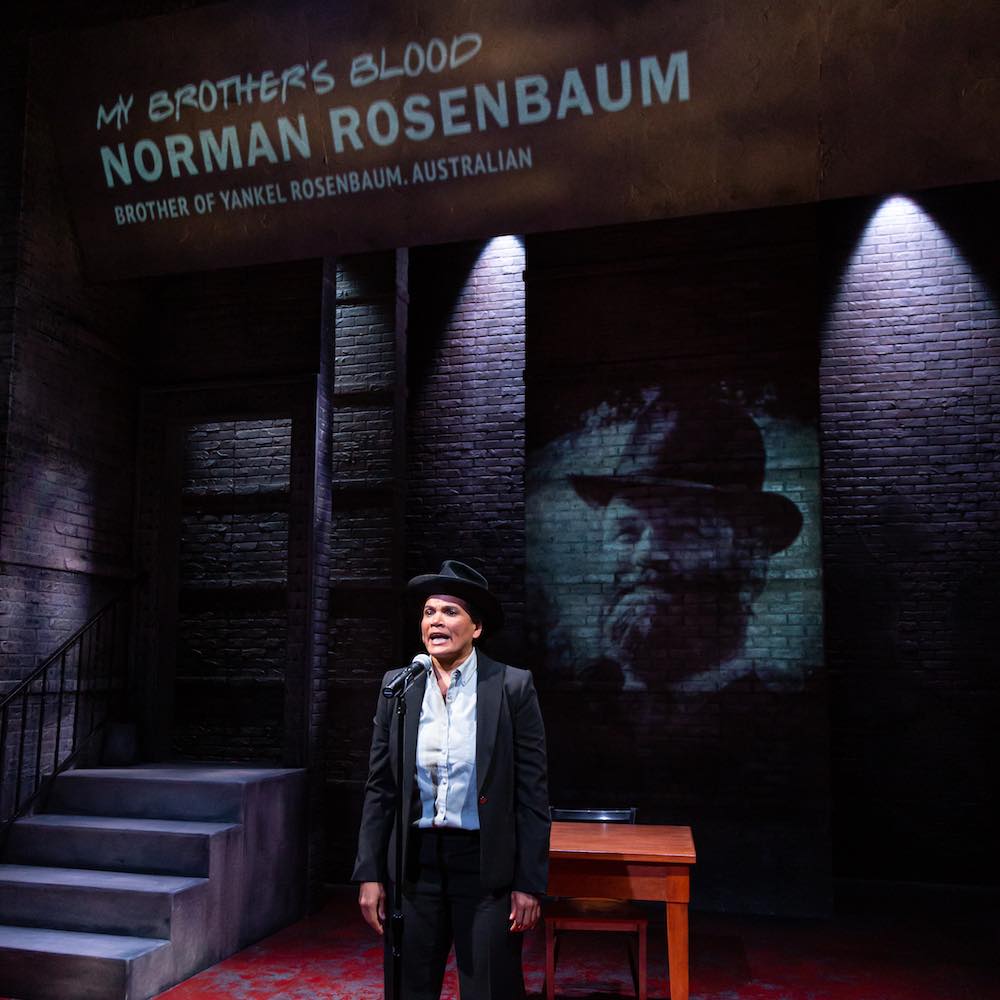

In the year following the events, Smith interviewed many witnesses and commenters, weaving excerpts from their statements into an intricately constructed fabric (not a narrative, in the conventional sense) of perceptions of the events and their meaning. The sole actor, January LaVoy in this production, portrays 26 different people in a series of brief monologues. LaVoy also co-directed the production with Theater J Artistic Director Adam Immerwahr.

The play demands that the actor represent, in quick succession, people who vary by race, religion, ethnicity, culture, age, sex, position, and education. LaVoy does so compellingly. Each individual is distinct, in terms of voice, physicality, and emotion. There are no false steps, no lapses in authenticity. Pamela Rodriguez-Montero provides LaVoy with readily changeable costume pieces — jackets, ties, hats, scarves — that make immediately visible where each character fits in the complex mosaic of Crown Heights.

When I say that LaVoy “represents” the various people Smith interviewed, I mean that she does not attempt a literal impersonation of them. But she faithfully conveys what they have to say, in a way consistent with who they are, giving the audience the chance to consider and understand their contrasting perspectives. Meanwhile, Bradley S. Bergeron’s projections — which at other points provide illustrative scenes from the neighborhood — display a photograph of the person LaVoy is playing at the time.

Nepheile Andonyadis’ set design, all gray brickwork, and Tosin Olufolabi’s sound design, which before the show and in the background of many scenes provides ambient traffic and other city noises, establish the firmly urban setting of the play. It’s not a specifically Brooklyn setting, like one might find in a Spike Lee movie. It could be any city, which may be the point.

Smith’s arrangement of the scenes is exquisite. Roughly the first half of the show explores, sometimes indirectly, the kind of identity issues that ultimately drive the conflict in Crown Heights. A Haitian American high school girl talks about the stylistic and social divides between Black and Hispanic girls in her school. Al Sharpton talks of modeling his hairstyle after that of James Brown, followed immediately by a Hasidic woman’s discussion about the role of wigs in her life. Angela Davis addresses Black/white race relationships analytically, while another Black academic, Leonard Jeffries, provides a more intensely ideological take on the subject.

The second portion of the show deals directly with the Crown Heights conflict. Different people see the same things differently, based on the experiences of their communities and their own lives. An ambulance operated by the Hasidic community arrives at the accident scene. Did its personnel simply assist city EMTs, as requested, or did they ignore the injured Black children?

Looking at history, which was worse: American chattel slavery or the Holocaust? That people Smith interviewed think the question is worth debating speaks eloquently about the strength of the competing grievances of the groups involved and how their ways of seeing the world are influenced by the long histories of racism and anti-Semitism.

From the point of view of a spokesperson for the Hasidic community, the crash that killed Gavin Cato was simply an accident, no malice involved, while the killing of Yankel Rosenbaum was an anti-Semitic murder by Blacks who hate Jews and celebrate Hitler. In an impassioned speech, Yankel’s brother, Norman, demands justice, his speech coming just before a section recounting how, at home in Australia, he is shocked to learn of his brother’s death.

From the point of view of Black residents and community activists, the Hasidic community is privileged, enjoying the racially tinged favor of police and city officials. Why are Jews allowed to drive, carelessly and too fast, down a main neighborhood street, kill a child, and suffer no consequences? Gavin Cato’s father’s solemn grief over the loss of his son speaks louder than any outpourings of rage. Smith’s script and LaVoy’s acting capture the truth of, and the contradictions among, all the voices.

Fires in the Mirror shows members of two groups, each marginalized in its own way, deeply distrustful of and full of hostility for each other, unable to agree on facts or what they mean, not truly listening to one another or recognizing their shared humanity. Such a dynamic is not limited to 1991 Brooklyn, and Fires in the Mirror is far from simply a documentary about a half-forgotten conflict from the past century. In a country far more divided and distrusting than 30 years ago, the play’s resonance is more alive than ever, a mirror of our own time worth seeing and reflecting upon.

Running Time: One hour 40 minutes, with no intermission.

Fires in the Mirror: Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and Other Identities plays through July 3, 2022, presented by Theater J performing at the Aaron & Cecile Goldman Theater in the Edlavitch DC Jewish Community Center, 1529 16th Street NW, Washington, DC. Purchase in-person tickets ($40–$60) online or by calling the ticket office at 202-777-3210.

Fires in the Mirror also streams from June 21 to 30, 2022. Streaming tickets ($60, good for viewing 10 AM to 11:59 PM ET) can be purchased online or by calling the ticket office at 202-777-3210.

The program for Fires in the Mirror is online here.

COVID Safety: In accordance with the Edlavitch DCJCC policy, all individuals will be required to show proof of full vaccination each time they enter the EDCJCC by presenting either digital documentation on a smartphone or a physical copy of their vaccination card. Individuals with medical or religious exemptions to vaccinations will be required to show proof of a negative COVID-19 PCR test taken within 72 hours of their arrival to the EDCJCC. All patrons in the Goldman Theater will be required to wear masks. Only performers and guests invited onstage may be unmasked. Masks are optional but encouraged in the Q Street and 16th Street lobbies, hallways, and other public spaces. Theater J front-of-house staff and volunteers will continue to wear masks. For more information, visit Theater J’s COVID Safety Guidelines.