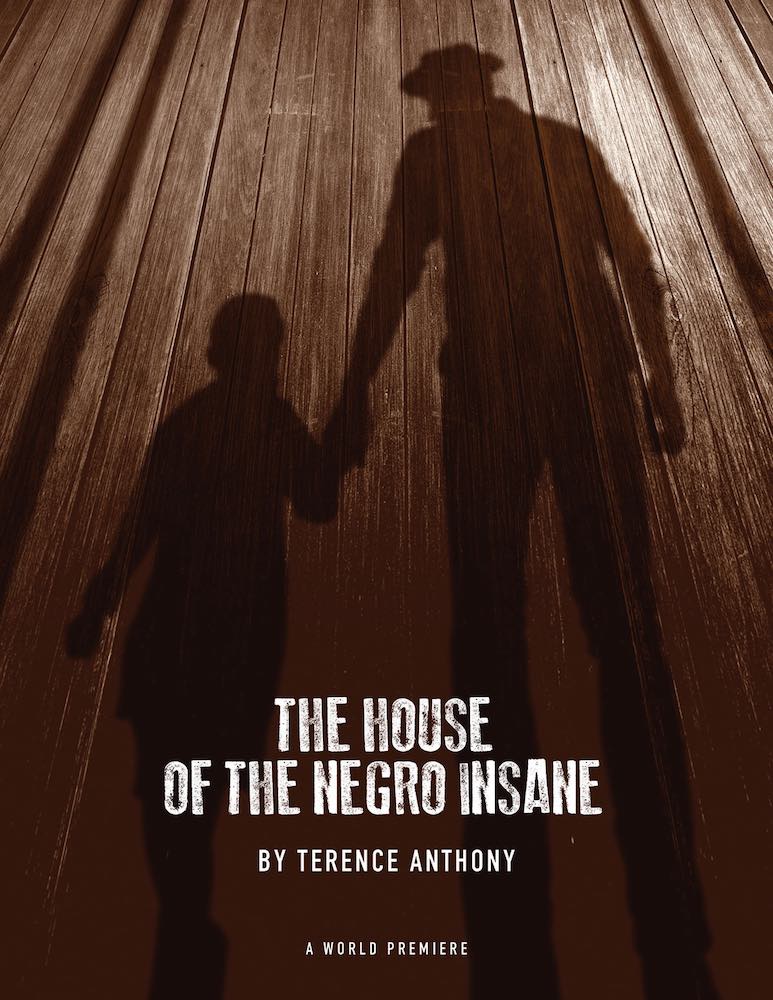

Terence Anthony’s The House of the Negro Insane, now playing at the Contemporary American Theater Festival in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, paints a picture of madness, violence, and death in a microcosm of Jim Crow America. The setting is a carpentry shop in a mental hospital for Negroes in segregated 1935 Oklahoma (only 14 years after the Tulsa Massacre), a cage within a cage within an oppressive society.

The carpenter, Attius Grimes, a powerful Jefferson A. Russell, builds coffins for the many inmates who do not survive the lack of food, poor medical care, and brutal treatment — including what can only be called torture — meted out by the staff. Taft State Hospital was not unique. An equally understaffed and overcrowded chamber of horrors in nearby Anne Arundel County, Maryland, gave Anthony many of his ideas for the play.

In the shop, death surrounds Attius, as he carefully builds his simple wooden coffins. His workplace is a box that confines him, but it’s also the closest thing he has to a safe space, unseen by the “blue shirts” who police the lives of the inmates in the main building of this total institution. Attius is most free when he is alone, working autonomously, sometimes letting his imagination roam to passages remembered from his father’s scratchy record of Stravinsky’s The Firebird.

From the beginning of the play, Attius must deal with the disturbing, part-time presence in his space of a white man, Henry (Christopher Halladay). Forgetful and at least half-mad, Henry sometimes exhibits a strange form of courtesy, from which he can turn on a dime to racist demands and threatened or real violence. He sometimes tries to ingratiate himself with Attius, repeating that Attius is his only friend, a sentiment Attius emphatically does not share (the first line of the play has Attius muttering “son of a bitch” under his breath as he sees Henry in the shop).

Henry is a reminder that a social order based on an insane racial caste system does not spare the sanity of members of its upper caste. A lower-class white man, who hates being called a “hayseed,” Henry deeply resents being hired out to a local farmer, while at the same time lording his superior racial caste position over Attius. Halladay conveys, in convincing detail, the contradictory wounded and hateful parts of his character’s fragmented self.

Attius regards Henry, and most of his world, with anger that is only barely suppressed, the terrifying sources of which become evident as the play proceeds. Russell uses this undercurrent of rage to drive the atmosphere of tension that pervades the play. The tension increases when Effie (CG) inserts herself into the shop.

With nonstop energy, Effie is someone who has moved around all her life. Attius wants her gone and tries to throw her out. Effie — an indomitable “hot potato of sass and resiliency,” as Tamilla Woodard, the pre-pandemic director of the CATF production, calls her — does not let anyone tell her what to do, and begins negotiating for a place with a stolen egg as her first bargaining chip.

The final piece of the picture is a 10-year old girl, Madeline, dropped off at Taft’s door by relatives who wished to be rid of her. Brought to the workshop by Effie, Madeline is young enough to follow older people’s instructions, even to the extent of lying in one of Attius’ coffins when he tells her to. Her spirit not broken, she brings some lightness into the shop, reciting poetry and dancing. Like the children in the recent touring production of To Kill a Mockingbird, Madeline is played by a young adult actor (Lenique Vincent; it could be difficult for an actual child actor to navigate the content of the play). While not completely convincing as a 10-year old physically, Vincent effectively portrays the innocence, sense of wonder, and fear of a child in a new, strange, and frightening environment.

Attius finds shelter in the darkness of the shop, hating and fearing the bright light of the outside world that has so damaged him. Yet Effie and Madeline begin gradually to pull him into the world; he cannot resist the tide of their energy and need. Effie affects him through her determination to escape, all the more so after she suffers a horrifying “medical treatment.” Madeline does so through storytelling, imagining a children’s story version of The Firebird that is about her and Attius. Attius must change to do what is needed to free Effie and Madeline from their captivity, in the process freeing his own soul. His growth is the strong emotional center of the play.

The violence that has felt inevitable from the beginning of the play erupts in a fiery conclusion. At this point, as well as in an earlier confrontation between Effie and Attius, fight director Aaron Anderson creates graphic and wholly credible confrontations among the characters. The violence has all the more impact in the intimate space of Studio 112, where audience members sit only a short distance from the action.

Claire Deliso’s scenic design involves a detailed, realistic evocation of a mid-1930s workshop, complete with a workbench, finished and incomplete coffins, wood planks, period tools, and a cot. The most dramatic coming together of John D. Alexander’s lighting design and Sarath Patel’s sound design is an overpoweringly loud thunderstorm midway through the story. Their designs work well together at quieter points as well, as in Attius’ Firebird reveries, when a warm special isolates Russell’s face as a passage from Stravinsky’s music plays.

Jerry Johnson’s costumes clearly identify the characters and where they stand in the institution’s society. Attius has a faded workman’s coverall. Henry’s outfit makes it easy to see why he is thought of as a hayseed. Most interesting, perhaps, are the shapeless blue sack dresses that Effie and Madeline wear, identifying their status as inmates as well as any traditional prison garb.

Anthony clearly intends to use the 1935 story to cast light on current reality. As Effie says, when white society no longer had Black folks in chains, they stuffed them in places like Taft. The point readily extends to present-day mass incarceration, and all the other legal, economic, and political devices used to keep Black Americans in a subordinate position. “Institutional racism” is made manifest in a literal racist institution like Taft Hospital, a point that would be hard for anyone watching the play to miss.

The actors, and Cheryl Lynn Bruce’s direction, maintain the play’s forward movement and sense of tension, foreboding, and incipient violence throughout. This constancy of feeling, and fine attention to detail in all aspects of a production that the audience sees up close and personal, make for a grippingly intense experience of theater.

Running Time: 110 minutes, with no intermission.

The House of the Negro Insane is playing in repertory at the Contemporary American Theater Festival through July 31, 2022, at Studio 112, 92 West Campus Drive at Shepherd University, Shepherdstown, WV. The performance schedule is online here. Tickets ($68 regular, $58 senior, or $38 for Sunday evening performances) are available online.

The Contemporary American Theater Festival program guide is online here and downloadable here.

COVID Safety: Masks must be properly worn (covering the nose and mouth) while inside any building for all CATF performances and events. You will be asked to provide proof of vaccination and a photo ID. The CATF complete COVID Safety Policies are here.