“Revenge,” Kurt Vonnegut wrote, “provokes revenge which provokes revenge which provokes revenge — forming an unbroken chain of death and destruction linking nations of today to barbarous tribes of thousands and thousands of years ago.” Richard Strauss’ Elektra compresses the culmination of one of the most famous chains of revenge in Western culture into 100 intense, utterly thrilling minutes in Washington National Opera’s current production.

The backstory: Agamemnon, seeking revenge for the Helen/Paris matter, wants to set sail to conquer Troy. The gods tell Agamemnon that to get favorable winds for his fleet, he must sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia. He does. His wife, Klytämnestra, takes revenge by killing her husband. Agamemnon’s other children, Elektra and Orest, then seek vengeance against Klytämnestra.

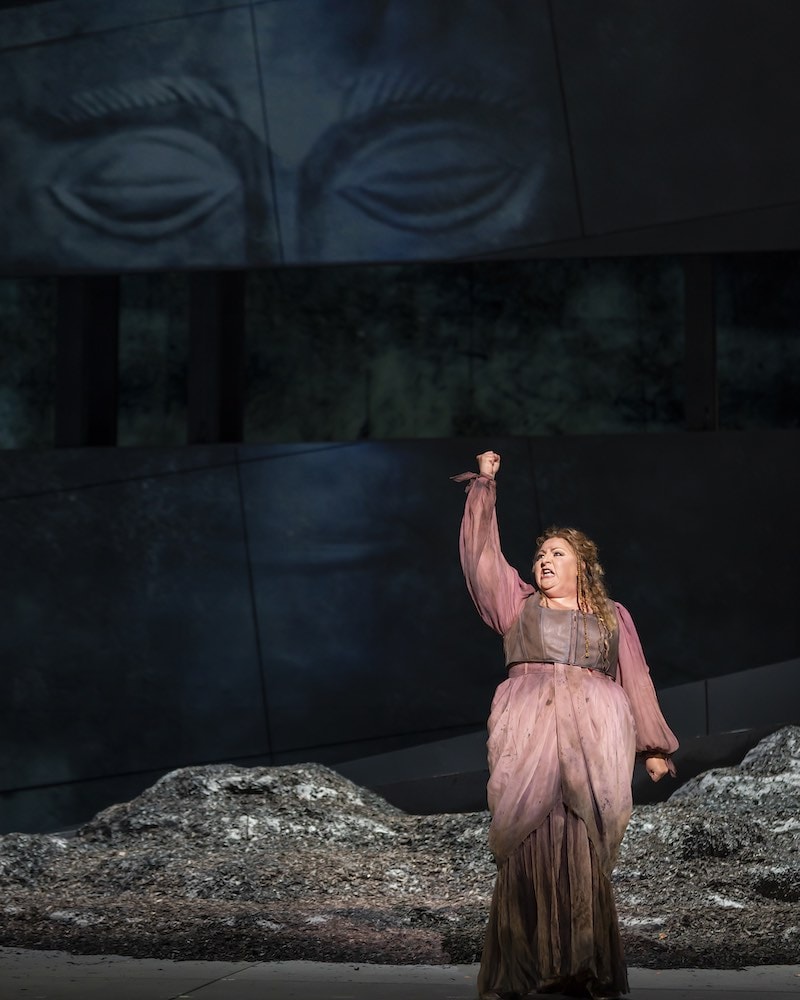

It is at this point that the opera begins. Elektra (Christine Goerke) paces the stage, full of furious energy, her obsession to kill her mother uncontained. Goerke is spectacular in the role, her vocal and emotional strength overwhelming. I have not heard a dramatic soprano of her power and precision on a Kennedy Center stage since I saw Galina Vishnevskaya in a magnificent 1979 performance of Britten’s War Requiem.

Elektra’s passion manifests itself in her ability to visualize acts of violence that she has not personally witnessed, whether looking backward to her father’s murder or forward to her mother’s being hunted and killed. In Goerke’s characterization and singing, Elektra does not so much imagine these moments as live them.

Elektra’s sister, Chrysothemis (soprano Sara Jakubiak), is of a different mind and heart, longing for a peaceful home and family. In a scene of intricate sororal dynamics, Elektra employs every psychological ploy in her considerable repertory to enlist her sister in the plan to murder their mother. Jakubiak matches well vocally with Goerke in their scenes together — no mean feat. Her character is as determined to pursue her objective as Elektra is hers, her more traditional femininity not to be confused with weakness.

Elektra’s manipulations have more success with her intended victim. Strauss’ vocal and orchestral music for Klytämnestra (mezzo-soprano Katarina Dalayman) is noticeably lower in volume than for the other major characters, consistent with the physical and mental deterioration of the character. Illuminating her character’s fear in the anxious tones of her vocal lines, she leans on a scepter like a cane, her mind contorted by constant frightening dreams. Elektra toys with her prey, who wants to know what animal sacrifice will end her nightmares. Elektra enjoys leading her to the reveal of the intended blood sacrifice.

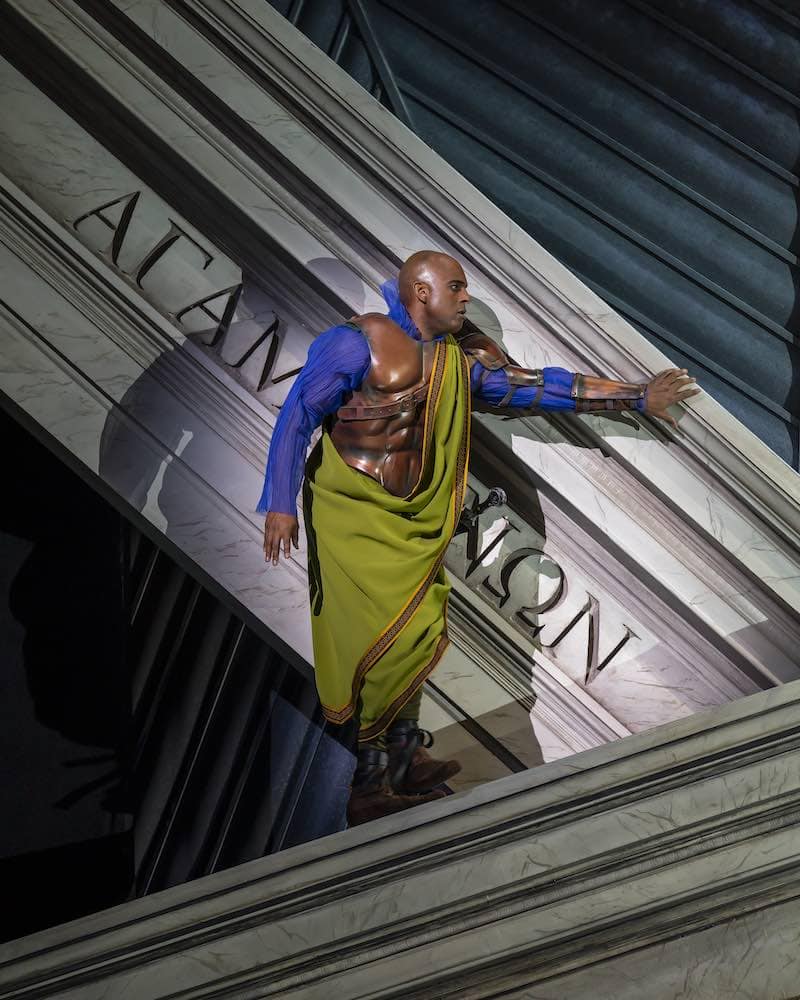

But what of Orest? Reported dead — much to the delight of Klytämnestra and her supporters — he turns up in disguise. After initially not recognizing him, Elektra joins him in a rapturous reunion. With a vibrant sound, bass-baritone Ryan Speedo-Green projects solid masculine strength in a scenario otherwise dominated by its female characters. This revenge has the sanction of the gods, and it is the man’s responsibility to carry it out. And when the job is done, he crowns himself king, Napoleon-style, in a brief, chilling touch at the opera’s conclusion.

Orest is up to the task.

The dramatic arc of the story is far more straightforward and propulsive than in many operas in the standard repertory. However, what I count as a weakness in the libretto is the anticlimactic appearance of Aegisth, Klytämnestra’s consort, in a short role for tenor Stefan Margita. In the peak moment of the dramatic tension of the opera, Klytämnestra has already been killed. Aegisth wanders on after the fact, his seemingly limited wits addled by alcohol. Elektra all too easily steers this inebriated, though far from innocent, lamb to the slaughter.

Too often operas bog down in stand-and-sing stasis. Not this production. Director Francesca Zambello keeps the cast in constant, restless motion, their movement embodying the disturbance of their souls. Zambello’s direction also makes this production one in which the characters are as vivid as the singing. The staging is also consistent with the constant perturbation of Strauss’ massive orchestral score, which, under Evan Rogister’s direction of the Washington National Opera Orchestra, contributes not just expert accompaniment to the singers but power and color of its own, especially in passages featuring the brass.

Erhard Rom’s set is an interesting mix of classical and modern. There is a tall column and fallen pediment pieces, on one of which “Agamemnon” is spelled out, suggesting the decline of the state’s legitimacy. Portions of a death mask of Agamemnon are projected onto the set at times. Much of the rest of the set is massive and modernist, with structures at disquieting angles, suggesting to me, at least, the links between Bronze Age revenge and the revanchist nationalism of today.

Bibhu Mohapatra’s costumes are well suited to the characters and their differences. Elektra is in a pale, subdued outfit, contrasted with Chrysothemis’ flowing blue gown and the sparkling regal red worn by Klytämnestra. Orest is in blue, military garb, complete with armor.

There are a couple oddities in the staging of the latter portion of the show. The murders of Klytämnestra and Aegisth are depicted on a high, upstage platform slotted into one of the larger set elements, looking from the house almost as if in miniature. Following the tradition of Greek tragedy in which much of the violence takes place offstage, with the focus on characters’ reactions as they hear of it, could have been stronger. In the midst of the mayhem, Elektra forgets the axe she intended to give to Orest, leading to what played as an “oops” moment and drew a probably unintended laugh from the audience.

Starting with the vocal performances of Goerke and the rest of the cast, Washington National Opera’s Elektra is a stunningly effective mixture of all the elements that make opera worth attending. It was among the very best opera experiences I have enjoyed in my decades in the Washington area.

Running Time: One hour 40 minutes, with no intermission.

Elektra plays five more performances from October 31 through November 12, 2022, presented by Washington National Opera performing at the Kennedy Center Opera House, 2700 F St NW, Washington, DC. Tickets ($45–$269) are available at the box office, online, or by calling (202) 467-4600 or (800) 444-1324.

The program for Elektra is online here.

COVID Safety: Masks are optional in all Kennedy Center spaces for visitors and staff. If you prefer to wear a mask, you are welcome to do so. See Kennedy Center’s complete COVID Safety Plan here.