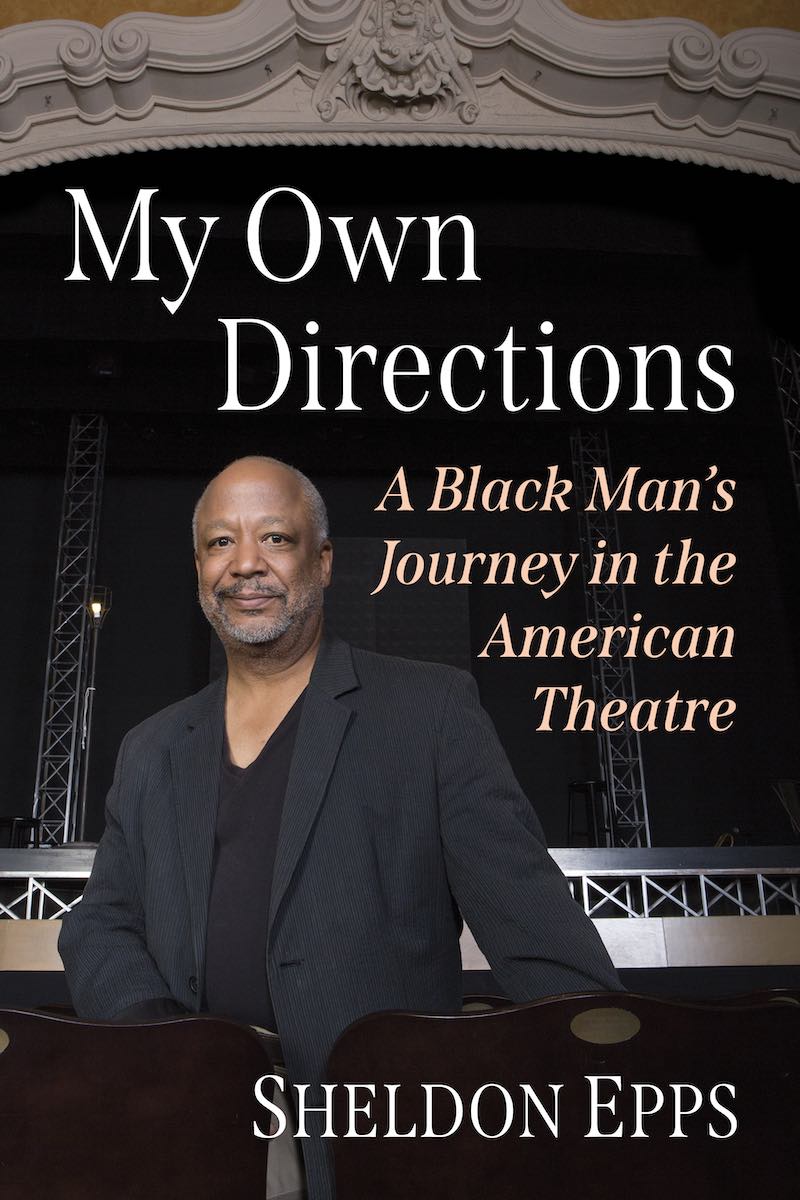

Sheldon Epps is regarded as one of the most successful and universally respected leaders in American theater. His new memoir, My Own Directions: A Black Man’s Journey in the American Theater (McFarland, 2022), shares his inspirational story of what it took to serve at the helm of the Pasadena Playhouse for 20 years as one of the few Black artistic directors in the country. Along the way, Epps describes the opportunities and challenges of decisive events that led to his directing major productions on and off Broadway and across the country, including in DC, and even London.

The list of premiere actors, designers, and writers who have been touched by his work reads like a “Who’s Who” in American theater arts, including television. Epps recounts “the roller coaster ride of life in the theatre” and is particularly forthcoming about being “chased by race” along the way. (See “Chased by Race,” an excerpt from the Prologue to his book, below.)

Throughout the high and low points, Epps was able to stay focused on the task at hand and lead through what would appear to be insurmountable challenges and circumstances. He states: “Sometimes, those who serve in the position that I held just have to operate by their theatrical gut sense of what is going to work” and get it done. Epps made a major life move when he accepted the position of senior artistic director at Ford’s Theatre three years ago. He hopes that the book “contributes to the ongoing evolution of the theatre industry.”

I talked to Epps about his career, opportunities, and choices to understand and share his life journey through theater. (Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.)

Throughout the book, you are confronted by crucial steps, seemingly insurmountable challenges, and caustic situations. Yet you find a way to persevere through and not just survive but thrive to new, sometimes unexpected heights! This is such an inspiring message in this “post-COVID” period when people are trying to return to their lives and dreams. What kept you going, fueled your tank, kept your eyes on prizes that sometimes you didn’t even know were there?

Sheldon Epps: Thank you for those kind remarks. I had the gift of coming from a very supportive family and community where people my age coming up during the late ’50s were encouraged not to accept limitations and instead to have big dreams and try to achieve them. I was also inspired by watching my father, a minister, who was driven to accomplish so much, and lead congregations from Compton, California, to Teaneck, New Jersey.

Outside forces have a tendency to put you in a “Black box” and define your choices in life, and I just had something burning inside that rebelled against that.

My career and my life continue in a way to just being a freedom fighter — I just wanted to have the same right to my artistry as any other artist.

There was also this constant need to go forward, to go to the next step and not to settle with the known. All that along with an artistic hunger to not repeat myself kept me going.

You describe magical theater moments such as “…theater could ignite the human passion for dark to light, tragedy to celebratory.” What does theater mean to you as part of the human experience?

The thing I love about the theater is that it is so immediate and so present. There’s a connection between all involved, an actor telling the story and the audience receiving it. It’s a shared experience. There’s a circle of energy that transmits out from the stage to the audience and circles back to the actors, a cause and effect on stage. Being right there with someone sharing the experience and breathing the same air — it’s electric, you can feel it. The actors are affected by the laughter in the audience and also the silence, profound attentive silence, that relays back to the actors on stage.

The pandemic has affected us in ways that we’re just starting to appreciate and understand, altering how we connect with each other.

Absolutely! We are wired for human connection. The pandemic altered that. We have need for human contact, touch, life, and energy. When we were all isolated and alone, we diminished the talent for human contact.

That’s why live theater is so important, to keep us connected, experiencing human emotions together in one specific place, listening to each other’s reactions, and getting energy from that. Including, and maybe especially, the actors.

How about when you embarked on new projects without experience, when you sometimes admitted to yourself you weren’t even aware of your next steps?

Sometimes you learn how to do it by doing it. I also learned as an artist, you don’t always have to have an answer on the spot. It’s quite OK to take a minute, regroup, and say I don’t know right now, but I’ll get back to you on that rather than just jumping out there to fill the space and air. Instead, sit someplace in silence and let the answers and responses come to you.

Accepting the role of associate artistic director at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego, for example — now, that’s a bold move.

[Laughing] There’s an example of “boldly going where one must go.” Actually, the people there were not much different from my artistic colleagues at the Playhouse. And truth be told, there was more diversity there than the early conditions at the Pasadena Playhouse. The Globe never felt as restricted, racially, as the Playhouse. The Globe was already doing August Wilson plays and had more people of color in the audience. In comparison, the racially and culturally limited programs at the Pasadena Playhouse when I started felt inherently wrong to me artistically and socio-politically and needed rectifying. So, I went about making that happen.

How did you do that?

In connecting to people on an artistic level I just overlooked the opposition and aligned with those who shared a vision for a stronger diverse representation at the Playhouse. Of course, I couldn’t have done anything alone — it took enlisting a village of support, and they stood and represented, giving me strength and the theater as well to keep moving forward.

The book is a flashback to the greats, especially considering your work on Broadway — Della Reese, Diahann Carroll, and André DeShields to name a few. You paved new pathways with amazing artists.

Yes indeed, Diahann Carroll, for example, was stunning to work with. She had a lightness, an effervescence about her you could feel when she walked in the room. The cast and crew were affected so much they almost couldn’t work, they wanted to just be in her presence and be mesmerized just watching and listening to her.

And the description of your production of Fences was exciting. Those who saw the Broadway production were blown away, but there was apparently something absolutely magical about the Pasadena casting.

The availability of top box-office actors just worked out perfectly. Lawrence Fishburne and Angela Bassett were captivating on stage in a way that took everything to a new level.

The hits just kept coming — until they didn’t. You went through a particularly devastating period when after so much success and acclaim, the stock market tanked, funding and resources dried up, nay-sayers were castigating you ferociously, and the theater closed temporarily, but somehow you turned things around. The book is must reading to gain insight and inspiration from that alone — I really liked how it isn’t a catalog of events but goes deeper as an exploration of possibilities as you were working through all that. How did you venture out of that darkness to a new positive reality?

That was a dark period indeed. The accusations were painful. Some said I was forcing diversity where it didn’t belong. That’s when I took a long hard look at the situation in front of me and dug deep inside to listen for the next steps, literally stopped and listened. There were times I sat in the dark, empty theater, just me and the ghost light. Only in the silence could I hear the voices, to keep going, that it’s going to be alright.

Silence is powerful, isn’t it? We’re surrounded by noise and chatter. It’s quite astounding what you can hear in the silence, right?

Definitely. There are forces that will keep you going if we take the time to just sit, be still and listen. The answers are right there, almost channeled from inside of and coursing through you. That’s what got me through, in leveraging the goodwill and faith of those who believed in us, making good choices, decisions. If you allow yourself to hear the answers, the universe will give them to you.

Fascinating. Once you got the theater back on its feet, you had even more accomplishments and box office success that nearly exceeded what had gone on before!

In the second half of my 20 years at Pasadena Playhouse, we were among the first to produce the Janis Joplin musical among other hits.

Theater-goers in the DMV have witnessed your work and didn’t even know about it — I saw that musical when it toured here. You developed Blue with Molly Smith at Arena Stage some years ago, and Twelve Angry Men at Ford’s Theatre just before the pandemic hit. What is it about the Washington area that was enticing enough for you to take the position of senior artistic advisor at Ford’s?

Paul R. Tetreault, Ford’s Theatre director, heard about my production of Twelve Angry Men at the Playhouse and asked if I would direct a local casting of the show. That connection led to further discussion of possibilities and eventually the offer.

In terms of the move, the Washington, DC, audience I feel is one of the brightest audiences in the country. Smart, passionate, committed. There’s a real dedication to building a theater community and I am happy to be part of that.

Well, we are thrilled and delighted that of all of the theater venues in the country, you chose to be part of the DMV at Ford’s Theatre. Your book provides fascinating insights about your life choices as part of the entire theater experience and really is a must-read. Thank you so much for taking the time to share with us.

My pleasure.

Chased by Race

By Sheldon Epps

Excerpted from the Prologue to My Own Directions: A Black Man’s Journey in the American Theatre by Sheldon Epps (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company) copyright © 2022 by Sheldon Epps. Reprinted by permission of the author and publisher.

If you are a person of color in America, race is always a factor. Being chased by race is often a terrible reality, and it can sometimes be an advantage. But it is always a factor in your life. I knew that from a very early age and accepted that as part of my very being. I had no choice. Nor did I want one. I am proud to be a Black man in America, even with all of the challenges, the slurs, the preconceptions and abuses that come along with that designation.

What I also wanted was to be celebrated for my race, to be celebrated by myself and others for being a Black man in America! A Black artist in America and a Black man in the American Theatre. I want to be recognized and honored for my race but not to be defined by it, and most certainly never to be constricted or diminished because of what I regard as a wonderful embellishment to my very being.

When you grow up in an African American neighborhood, you actually don’t walk around thinking about being Black all of the time. It is simply a part of your existence, much like breathing. You don’t necessarily think about it until something makes it difficult for you to breathe. And as we know all too well, that can sadly happen at any moment. But if you have had great support from a loving family and a smart and emotionally well-balanced community, you learn to think about being a person of color as a great advantage. You learn to speak of your race with pride. Also, you very quickly learn that one of your additional burdens in life will be to “represent” your race well.

Like many men of color of my generation, especially those of us who have had great advantages on our path through life, I always knew that I shouldered that additional burden. The truth is that I have resented it at times and wanted to set down that heavy load. But I knew that I could not. I had that strong family background and that supportive community. I was taught to view my racial heritage and my skin color as rich and wonderful parts of who I am. I was encouraged to think that if I worked hard enough I could do anything I wanted to do and be whatever I wanted to be.

For me, that was the desire to have a life in the theater, first as an actor and ultimately as a director. I decided early on that I wanted the world to think of me not as a “Black Director” but as a director who had the good fortune to be Black with all of the skills, the wide-ranging knowledge, the soul and the proven ability that went along with that appellation.

One would think that this would not be a problem in the supposedly highly evolved world of the American Theatre, which is presumed to be more liberal and forward thinking than many other fields. One would be wrong! I did achieve that goal. At least among those who allowed that goal to be achievable. Sadly there are many who do not. As the great writer Toni Morrison once said, “I’m tired of it! So I’ve decided to let racism be the racist’s problem, not mine.” Those simple words were a great release for me, and they allowed this Black man to be defined by his work, his ability, his ambition, and both his failures and his successes, not by his skin color.

There have been many moments when I have felt the pressure of what James Baldwin and Toni Morrison identify as “the White Gaze.” The additional challenge that comes from the desire to exercise your art without the necessity of proving to white society that you are good at what you do, according to and judged by white standards. It takes years to “knock the little white man” off of your shoulder. To avoid the white gaze and judge your work without looking at it through that omnipresent lens. That can be the “knee on my neck” that artists of color have been forced to deal with for many decades. We must fight constantly to get rid of it. We must fight to lay that burden down and stand tall.

I do not for a moment believe that the racial injustices that have chased me and burdened me as an artist in America are in any way tantamount to the brutal murders that have brought about protests after years of abuse. But the racial inequities that I have faced have their own brutality and ugliness. They have demanded that I fight back, that I shout, that I scream and that I light my own fires to shine the light on the racism and prejudice that has blocked my road and the roads of so many other artists of color over the years. This moment in time has allowed many to take the breath that is needed to raise their voices in protest and to honestly call out both the conscious and unconscious racism and prejudice that exist in our field.

My story is a unique one and carries some weight both in terms of triumphs and challenges. I have often been one of “the first” or one of “the only.” Sadly, during my two decades as artistic director of Pasadena Playhouse, I was always one of only three or four persons of color in a leadership position at a major theater, and for far too many years I was the only one. My hope is that my story can be both inspirational and a cautionary tale, with the ever-burning hope that those who follow may have fewer challenges than I have had, in part because of my journey.

Sheldon Epps has directed major productions on and off Broadway, in London, and at many theaters across America. In addition, he has had an active television career helming some of the classic shows of recent years. He was the artistic director of the renowned Pasadena Playhouse for two decades, and currently serves as senior artistic advisor at historic Ford’s Theatre in Washington, DC.