In the world of opera, some directors hold up a composer’s score like the holy grail, convinced that there is only one way to honor the composer and a work’s tradition. Others gain notoriety for “revisioning” works by clamping a pet concept onto a score, so the creator’s intention and work’s meaning are all but completely obliterated. The battleground had been much the same in theater, working with Shakespeare’s canon. But, from the mid-20th century, the rise of “auteur” productions has dominated, often more about a director’s ego than the work itself. (In the case of Shakespeare, I have often wanted to ask a director about his or her take on a Shakespearean production, “Have you ever read the fourth act?” Being inattentive to an Act IV can be pure folly; this is usually where an iron-heavy concept approach falls apart.)

Now, there is a third group of directors who seem, like aerialists high above an arena, to daredevil dance between the two extremes, and, while directing is always a dangerous sport, the experience can prove mesmerizing and even at times revelatory to those present below. Timothy Nelson, artistic director of IN Series, at his best, has been known to pull off such an aerial ballet.

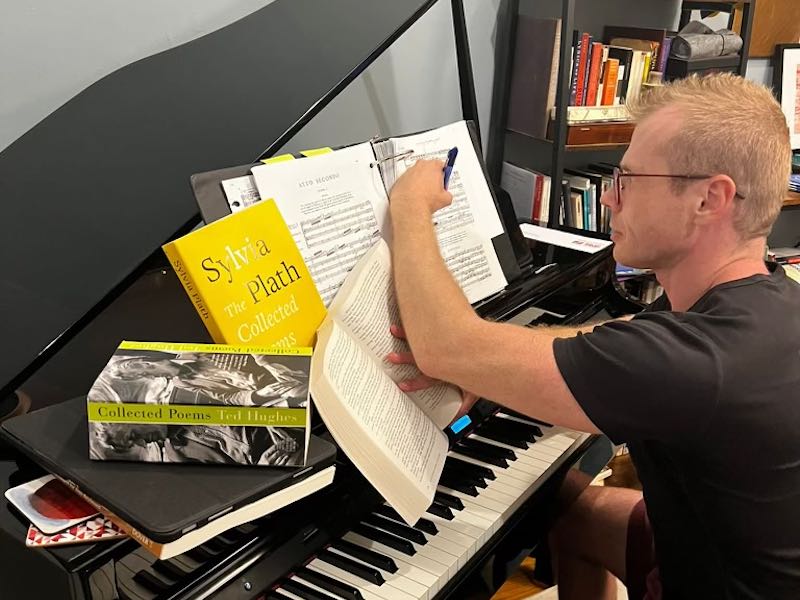

I had the chance to sit down with Tim, who opens his season with a world premiere of a staging of Alceste, based on the Euripides play Alcestis, with music by George Frideric Handel (from the composer’s two different operas on the subject) and — wait for it, love! —with texts plundered from poets Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, plus additional material conjoined from contemporary local playwright Sybil Roberts.

You said this work has been in your head for over ten years, what was your initial entry point?

Tim told me how, wandering around a flea market, he had come across a slim volume of four of Euripides’ plays. In it was Alcestis. He flipped to the end and was immediately arrested by the final words of King Admetus, whose wife is resurrected and restored to him, having been brought back from the Underworld by the courageous Heracles. Admetus brings to a close the rare 2,500-year-old tragicomedy with the words “For now we shall make our life again, and it will be a better one.”

The offer of hope and a new beginning spoke to him at a critical time in his life. ”The play ends as a beginning, only we don’t get to see it.”

What translation did you use? Richmond Lattimore’s?

Tim espied my own copy, and we both marveled for a time over Lattimore’s language and keen insight into Euripides’ almost modern sensibilities. The fifth-century B.C.E. playwright dared to show man not as an idealized classical hero but as he (or she) really is, full of complexity and changeable emotions. Also, as Tim said, “There’s also a notion of grace that speaks to us today and how sometimes, if we are lucky, the answer is yes.”

There is so much mystery in the play, don’t you agree? Why does Queen Alcestis sacrifice herself, accept death in her husband’s place? And why does he accept?

Tim agreed, saying, “We never know. But that’s why I felt I needed some other voices and perspectives brought in. I began to understand and even take the side of Admetus’ father. He challenges his son: Is his life of less value just because he is old, so why should he die?

The play and certainly Handel’s second attempt at the opera, with its lost libretto, seems incomplete. Why has this work held your attention for so long? And how did you start to reconstruct the lost shards? And why approach it as a play with music?

“The myth is one that has been used a lot in opera. There’s the early Handel and the later Handel. The later one had a libretto in English, but as you said the libretto has been lost so it’s just shards. But glorious shards! There’s one by Gluck. There’s a Lully. But it was the play that spoke to me. Then I struggled to settle on the right translation. As we discussed, I love the Lattimore. But when I found Ted Hughes’ version, I knew I had to use it. The language was so exciting, and Hughes goes big and wide.”

Would it be fair to call this project a “mash-up”? And don’t you enjoy “mashes”? Will you also admit that sometimes your “mashes” work phenomenally and sometimes —

He interrupted me laughing in agreement, “Not so much! Kind of like mashed potatoes. Sometimes you just can’t get out the lumps.”

So, why this work now?

Tim said that the reason has changed over the years. “At the beginning, it has to do with what was going on in my life then and the need to believe in the possibility of new beginnings and reinvention. Then, during COVID, it really became about life and death and my asking the question, ‘Who gets to live and why?’ Now there is some return to the original impulse but without the personal desperation. Something about the larger implications and, to quote Obama, the audacity of hope. I weary of the current endless political harangue and yearn to return to something more fundamental, simple, and powerful, and that is humanity’s capacity for hope. What is it to believe that the sun also rises?”

Yet you have integrated both Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, their writings, and something about their personal relationship. You must know that neither their writings nor their marriage had much to do with hope, so what is this about?

Tim confesses, “I would love to claim all of this was part of some original vision. I fell for the poet Hughes’ electric, powerful translation. Then I discovered, as one does about Hughes, you must excise a lot. But until we were workshopping it, I didn’t even know who he was. To find out he was Sylvia Plath’s husband made the work about this man whose wife has died.

Of course, many in the world indict Hughes, accusing him of being directly accountable for his wife’s suicide. Are you saying Plath’s suicide is to be interpreted in your vision as a sacrifice for him?

“Perhaps, yes. And Hughes/Admetus has to reckon with his own culpability. And, as subversive as this sounds, maybe he longs to reclaim her from the dead so they can have a second chance at life together on this earth.”

Then you must also know that after Plath’s death, Ted Hughes’ second wife, who was also a poet, and he, felt haunted by Plath. Do you see your production as Hughes’ longing to follow Sylvia down to the underworld? Sadly, Hughes’ second marriage also ended in something like a Greek tragedy. So, if there is reason to believe why Hughes made his translation in his later years, is there a connection to why Tim has made this work?

Tim assured me it happened providentially. His whole creative team was disturbed that there was so little of Alcestis in the original Euripides play with her name as the title. “So, as the Sylvia–Ted story became more salient, Sylvia became the vessel in which the story today would be an opportunity to give more voice to Alcestis. Plath’s poetry has now been inserted, including a whole big scene in the underworld where Alcestis gets to choose between life and death and has agency in that. But to be fair, we’ve also added other poetry by Hughes to fill out this story. In a way, it’s become the conversation they never got to have.”

Art imitates life imitates art?

Tim lets me into another major choice for this production. “Because there are only three main actors and they play multiple roles, through the use of masks, we think of the lens used as all being a conversation between a husband and a wife.

He also lets me into the thinking behind his musical choices. Some chorus passages were set by Handel in English. Some words by Hughes were originally in Handel’s Italian opera, now reset for scansion purposes in English.

I return to my theme, exploring with this artistic director who insists on high-flying aerial acrobatics.

Tim, are you ever concerned you might leave your audience down below in the dust?

“Yes.” Then he laughs cheekily, “Well, perhaps not as much as I should!”

Then he continues in a more serious vein, “I’m aware that sometimes I do, but I want my audiences to have a meaningful experience. Maybe I trust the audience more than I should.

“I have become less and less interested in audience alienation. However, you will remember, one of the first things I did in DC was a twist on Verdi, and a little old lady in the audience, within the first five minutes of a performance, ran out of the theater screaming, ‘This is unbearable!’”

Tim ties the process of developing his vision for a piece to the trajectory of his own development as an artist. “As I continue to grow as a director, I hope I will always strive to make pieces for opera and theater that work on multiple levels. I hope that over the years I will earn the trust of my audiences.”

Do you liken your work to an archaeologist excavating or — ?

“I believe I’m more like a sculptor working with found objects! I find things that seem antithetical to each other and explore putting them together so they seem new. I’d like to think I’m someone like what’s his name — Rausch—”

Rauschenberg?! You’re a Rauschie!

The world premiere of Alceste opens September 23 and 24, 2023, deep in the bowels of Dupont Underground, 19 Dupont Circle NW, Washington, DC, at 7:30 p.m. Saturday and 2:30 p.m. Sunday.

The following weekend the opera will be repeated at Baltimore Theatre Project, 45 W Preston St, Baltimore, MD, on September 29 and 30 at 7:30 p.m. and October 1 at 8 p.m.

Then IN Series comes back to DC for a final weekend of performances at GALA Hispanic Theatre, 3333 14th St NW, Washington, DC, on Saturday, October 7, at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, October 8 at 2:30 p.m.

Ticket prices for Dupont Underground and GALA Hispanic Theatre range from $35–$65; tickets for the Baltimore Theatre Project range from $20–$30. For more information and tickets, go to www.inseries.org/post/alceste