Think back on what you were taught in U.S. history classes, especially in your younger years. Probably a lot of downright lies, like the old fabricated story of Washington chopping down a tree and telling the truth about it. But how many of us were not taught that the so-called Founding Fathers who championed equality for all men were also slave owners? (And state legislation in places like Florida ensures these complicated truths are not explored in classrooms.) Histories that center the experiences and lives of those who were enslaved, exploited, and abused, and stories of resistance and rebellion in the Land of the Free… we don’t learn those narratives that create a fuller portrait of American history in our textbooks.

This is the thesis of the world-premiere Mexodus, written and performed by Brian Quijada and Nygel D. Robinson, onstage through April 7 at Baltimore Center Stage and from May 16 to June 9 at Mosaic Theater. This exhilarating theatrical experiment traces an erased history and sets it to a hip-hop-inflected score.

Quijada and Robinson researched a lesser-known Underground Railroad that led south to Mexico. After Mexico fought for its independence from Spain in 1821, the territory of Texas (formerly Mexico) was a contested site for several decades. From 1829, when slavery was abolished in Mexico, through 1865, the year of the 13th Amendment, over 4,000 (and up to 10,000) enslaved Black Americans made the arduous journey from the U.S. to Mexico, evading posses in the Texas territories looking for rewards and crossing the deadly Rio Grande, searching for freedom.

As they rap in the opening number and closing reprise, “We didn’t know this shit…. The facts we never learned in history class.” How can we ever move toward a more perfect union without this knowledge?

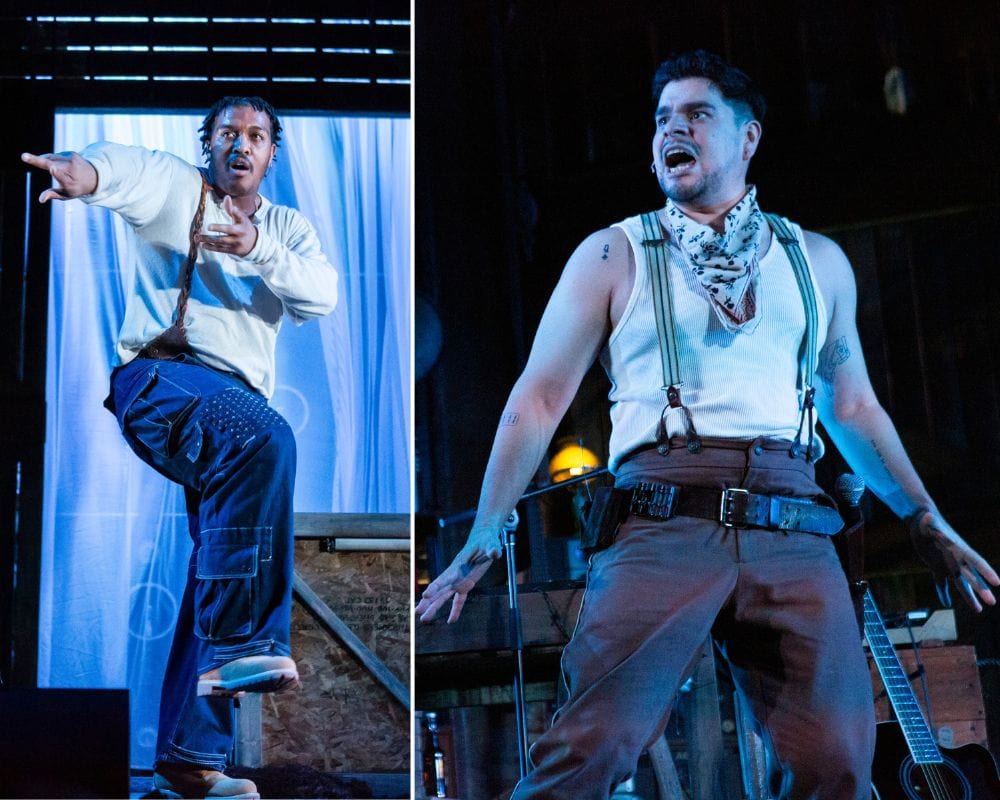

In Mexodus, they tell the intertwined stories of Henry and Carlos. Robinson plays Henry, a young, enslaved Black man who was ripped away from his mother during his childhood and forced to do hard labor, and who flees to Mexico after killing a slave owner in self-defense. Quijada plays Carlos, with a backstory less well known to most USians: he was a Mexican soldier who fought for and helped secure his country’s independence from Spain, but lost everything — his family, his homestead, his livelihood — in the process, and is now an inexperienced tenant farmer working land owned by someone else and fearful of U.S. invasion. When Henry almost drowns crossing the Rio Grande, Carlos takes him in and they begrudgingly live together, until both a flood and Henry’s fugitive status bring them closer than ever. “Todos estamos juntas en esto, we’re all in this together,” Carlos explains.

In many ways, this is a standard two-hander in a bottleneck situation, but not as conceived and performed by Quijada and Robinson and ably directed by David Mendizábal.

Mexodus is also an electrifying live-looped concert experience.

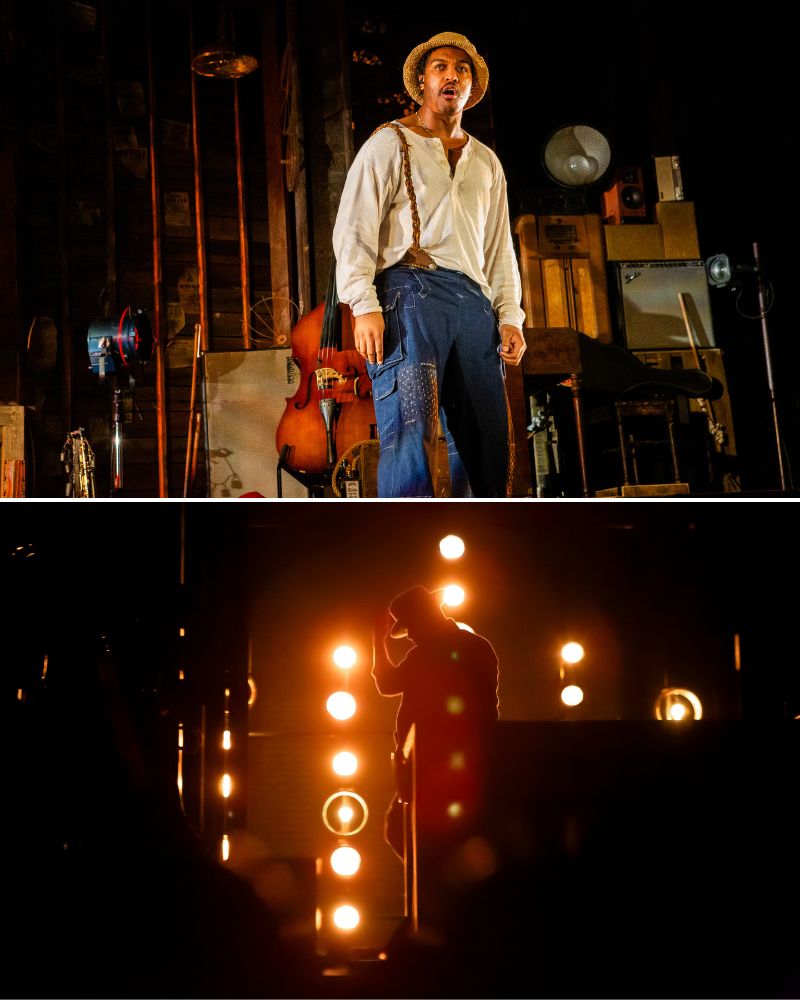

The deceptively simple stage setup — designed by Riw Rakkulchon — has a large barn door, a string of bare bulbs strung over the orchestra, cotton branches poking through wooden crates, and a variety of old-timey speakers, musical instruments, and audio equipment stacked at either end of the stage. Quijada and Robinson crisscross the stage, picking up and playing various instruments, recording a musical passage or vocal motif into microphones, and stomping on the sound-effect boards scattered across the floors to create and loop the music that they then sing and rap over.

Robinson plays standup bass, piano, keyboard, and trumpet, and sings with a powerful, crystalline voice. Quijada plays accordion, guitar, harmonica, and percussion, beatboxes, sings in a gruff bass-baritone and raps at a lightning pace in both English and Spanish, and remixes everything at a central soundboard, disguised as a wooden crate. Audio engineer Simon Briggs also deserves recognition for his sonic wizardry.

In an extended comic scene, we watch Carlos work on the farm, performing on different percussion instruments, and Henry occasionally joining in by banging on his tin coffee mug. During a threatening storm, Robinson plays the piano and sings his heart out in a moving gospel number while Quijada conjures up a dysphonic storm on his soundboard. And during the opening night showstopper “Henry 2 Enrique,” they teamed up to create a full-on concert experience, rapping together in English and Spanish, and bringing the audience to its feet

It’s a high-stakes gamble to create their own score each evening, but they display a handful of aces, becoming their own full symphony and creating layered, complex tracks. The songs are the American dream of the melting pot, bringing together elements of both traditional and contemporary musical styles based in the U.S. and Mexico: Black spirituals and gospels, R&B harmonies, interpolations from hip-hop classics, Spanish classical guitar, and Mexican folk ballads, in addition to more traditional musical theater style ballads. All of this they perform with not only a technical mastery but an exuberance and joy.

The North Carolina-born DC transplant Robinson shares a personal story partway through the performance, noting that he is living the “wildest impossibilities” of his ancestors. Likewise, the Chicago-born and -based Salvadoran American Quijada shares his first memory of anti-Black racism.

These moments, along with their opening and closing numbers frame the musical as poly-temporal: it’s exploring the past through the hopes and fears of contemporary Black and Latinx Americans. The legacy of slavery and the treatment of people entering the U.S. through Mexico are ongoing and urgent. In their final number, they warn that “Black and Brown bodies continue to be hunted… America forgot she was supposed to welcome all.”

There are a few hiccups in Mexodus: sometimes the recording of the loop (as fascinating as it is to watch) pauses the plot progression or even dialogue; the characters feel more archetypal than fleshed out; and the farewell between Carlos and Henry seems overlong as they say goodbye over three songs. But that does not take away from this innovative and impressive theatrical experience. Head to the theater early to watch the accompanying documentary film playing and to visit the theater’s Indigenous Art Gallery.

Yes, Mexodus is deeply indebted to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, but it’s all the more powerful for that. If Hamilton leads to a hundred such musicals that sing to today’s audiences while exploring U.S. history through a contemporary lens, offering a brave space for writers, actors, directors, and creatives from underrepresented backgrounds to tell our complex histories, and providing an education in civics, we will all benefit from this. Todos estamos juntas en esto.

Running time: 85 minutes with no intermission.

Mexodus plays through April 7, 2024, at Baltimore Center Stage, 700 North Calvert Street, Baltimore, MD. For tickets ($39–$74, with senior and student discounts available), call the box office at (410) 332-0033, or purchase them online.

The program for Mexodus is online here.

Mexodus then plays from May 16 to June 9, 2024, presented by Mosaic Theater Company performing in the Sprenger Theater at Atlas Performing Arts Center, 1333 H Street NE, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets ($42–$70) online or from the Box Office at (202) 399-7993 x501 or [email protected] from 11 AM–5 PM Monday through Friday, or two hours prior to a performance.

COVID Safety: Baltimore Center Stage’s current policy includes mask-optional performances on Thursdays, Saturday evenings, and Sunday matinees, and mask-required performances on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturday matinees. During those performances, masks may only be removed in designated eating and drinking areas. For more COVID-safety information, please visit here.