I finally saw Wicked on Broadway in early 2022. I went in blind, and as I left, I was sad to find that I felt underwhelmed. Unmemorable, plotless songs plagued the performance, and the show centers oversimplified, cartoony characters in a story about leading causes of America’s current, renewedly urgent crisis.

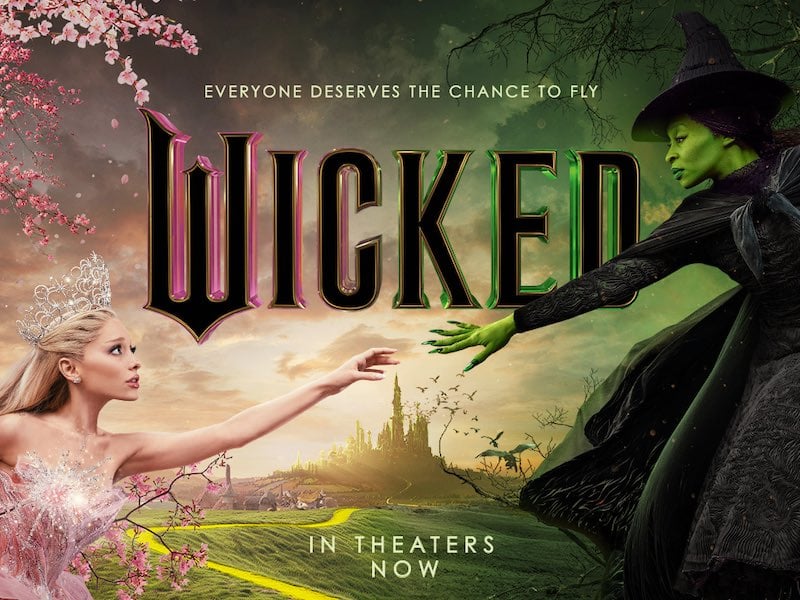

The Wicked movie released this past week, directed by Jon M. Chu (Crazy Rich Asians, In the Heights) and starring Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande, has erased these issues.

This film has improved on its source material for the same reason that Spielberg’s 2021 film West Side Story improved on the 1961 film version: it brought its source material’s symbol-based, exaggerated, made-for-musical-theater plotline into reality, taking stock characters and reconnecting them with our real world.

The stage version of Wicked — with its music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz and book by Winnie Holzman —gives us a cast of stock characters and too many unmemorable filler songs and pairs them with a story about a demagogue-led regime swindling large swaths of society into believing they are good and those who oppose the ruling ideology are evil. The ruling powers begin rounding up members of vulnerable communities and siccing law enforcement on its justice-seeking political enemies. Meanwhile, Elphaba’s character and song quality resemble Disney Channel fare.

This left something in my mouth somewhere between disappointment at a missed opportunity and a bad taste. It felt like the other Stephen Schwartz joint, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, this time with even less “God Help the Outcasts” and even more “A Guy Like You.”

Of course, you have to start somewhere in breaking what’s going on these days to America’s youth and politically unengaged, and in trying to make a great night out to see a megamusical “meaningful.” But I couldn’t help but feel quietly upset coming out of the Gershwin about Wicked’s lack of nuance in talking about these issues. It makes the show feel like less of a cautionary fable and more of a fairytale — not the best aesthetic for a textbook political allegory for America’s current struggles.

Wicked has been occupying the cultural pedestal that is Broadway — and its largest theater to boot — for over 20 years now. In a time when we desperately need to reach people about the gradual creep of fascism, which is starting to have crept, the Broadway narrative can feel too exaggerated and surface-level to have a chance at sending people back to their hotels thinking seriously about the story’s implications for their own world. The show is great at what it is trying to be — sanitized, family-friendly Broadway fare with some serious themes that won’t get you down too much if you’re not a member of a community feeling some of these very real threats. But as a lover of family-friendly musical theater, I say thank goodness we have other storytelling media too.

In the new film adaptation of Wicked, seeing these characters act with the realistic personal emotional nuance that film is so suited to portray brings Wicked into the three-dimensional Technicolor it needs to tell its story.

Cynthia Erivo’s Elphaba enters the story with strength, fed-upness, and a quiet sense of profound mourning that has replaced stage Elphaba’s nervousness. Through much of the film, we are not sure yet how much Erivo’s Elphaba cares about the constant emotional wounds her peers, and even family, inflict. Erivo’s Elphaba is not a stock-character victim who wears her suffering on her sleeve. How often in real life is the complexity of someone’s wounds visible on the surface? A story about issues this complicated demands that mature understanding of reality.

Erivo’s Elphaba maintains a strength, but a human softness under her armor. In this, we find ourselves far more eager to root for her. She’s not just shy, grumpy, and “adorkable” — she’s a survivor, and, thus, far easier to root for. Chu has fully taken advantage of film’s ability to show us an actor’s face up close to share this with us.

Erivo’s performance gives narratively satiating, affecting complexity to Elphaba’s response to her ostracization that she and Chu beautifully weave through the film through performance, new dialogue, and new flashbacks that flesh out her own family’s role in casting her out. In one such scene, we see how Elphaba’s sister Nessarose, a wheelchair user, unexpectedly lacks empathy for her also marginalized sister.

You could reasonably expect that someone who casually supports bigoted groups and institutions in their day-to-day probably wouldn’t leave the live theater Wicked with their pulse rushing, head reeling, and face flushing. The movie, however, is a different story — and not one that feels contrived. It makes the issues at the center of this narrative feel real by emphasizing how bigotry based on the color of one’s skin can truly affect someone — not just a stock character ready-made for Broadway Ballads™ and merchandise, but a real person, a person of strength succeeding as best they can while they are wounded by the scars of the closed-minded, both on an everyday and systemic scale.

Meanwhile, Ariana Grande’s Glinda stays perfectly within the realm of a big, loud stock character — a perfect foil to Erivo’s Elphaba. This contrast between the superficial/attention-seeking/harmful and the thoughtful/empathetic/good sits at the core of Wicked — and we get to see here how this serves to flesh out both characters and Wicked’s narrative as a whole.

It is then, thanks to these two performances, that when we get our classic moments like “Popular” and “Defying Gravity,” the significance of what “popularity” and “defying gravity” actually mean comes to vivid life. The joy from and meaning of these songs become exponential as they provide narrative catharsis and real-life applicability on top of their legendary theatrical status. And what’s more, the filler songs that weighed down the stage show Wicked now shine for their lyrics and the role they play in further developing these now fleshed-out characters.

Obviously, Wicked on the stage is doing good, and of course, it probably wouldn’t do as well if it had the nuance and seriousness I’m suggesting.

But this film’s party scene, where a sullen, triumphant Elphaba dances in front of her cruel peers and turns her head to reveal a single tear, would not be possible on the stage of a megamusical. We couldn’t see deep into this character’s eyes to see the person behind this performance.

Given what we are learning about what half the country either wants in leadership or is willing to overlook, maybe a simplified story of fascism creep is pushing the limit for mainstream entertainment. Obviously, there’s nothing “wrong” with a piece of entertainment that’s just a good time. But the story Jon M. Chu has given us in his film adaptation of Wicked has maximized the insight Wicked can give.

This isn’t just a narrative fighting to be part of national cultural conversations, either. The stage show was made in 2003 — wasn’t Trump doing commercials with Grimace then? And this adaptation is, first and foremost, a wonderful piece of entertainment combined with do-gooding.

Jon M. Chu’s Wicked is a deeply compelling story that also brings a message that could do exactly the kind of good the world needs. You will laugh, you will cry — you will want to see it five more times. It’s exactly what a movie with a message should be.