BOOK REVIEW

Shakespeare in the Theatre: Shakespeare Theatre Company

by Drew Lichtenberg and Deborah C. Payne

Bloomsbury, 2024

13-minute read

The ghosts of the Founders walk the streets of DC. What are they thinking? We cannot know. But one thing some among them — Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams — have in common is a deep love for the works of William Shakespeare. Drew Lichtenberg and Deborah C. Payne share that devotion — their eminently readable history of the Shakespeare Theatre Company is a beautifully written, nuanced paean to DC, to theater, and to the role of Shakespeare in America.

Drew Lichtenberg is the resident dramaturg and artistic producer of STC. Deborah C. Payne is a scholarly consultant and professor of literature at American University.

Their book is part of the Arden Shakespeare in the Theatre series, which introduces readers to theater directors and companies whose work has been influential and transformative. Series editors Peter Holland, Farah Karim-Cooper, and Stephen Purcell assert that each book also “reflects upon…the broader artistic, cultural and socio-political milieu” surrounding the productions.”Lichtenberg and Payne also remind us (if we need reminding) that, thanks to its hyper-political atmosphere, DC is indeed a Shakespeare town.

The book aims to trace the history of STC: cultural, social, and political. It also deals, inevitably, with the pressures of the marketplace. In all these aspects, it is a resounding success. Lichtenberg and Payne do not shy away from controversial issues or missteps. Theirs is a balanced portrait, and it is refreshing to read such an unsparing account from theater insiders. There are many intriguing stories to recount, but they are a mere fraction of what you will find in the book itself. In a sense, the Shakespeare Theatre Company is a tribute to not only the donors, artists, production staff, and two iconic artistic directors, Michael Kahn and Simon Godwin, but to everyone who contributed to the extraordinary institution it is today. Perhaps, even the critics. (Well, maybe not.)

Shakespeare in DC: The President, the Library, and the Theatre

Shakespeare’s influence on American culture began early. On April 14, 1865, at the Ford’s Theatre in DC, John Wilkes Booth, actor and scion of a well-known acting family, shot Abraham Lincoln. As he jumped down to the stage, Booth yelled Brutus’ line from Julius Caesar, “Sic semper tyrannis!” Another seminal event was the founding of the Folger Shakespeare Library in 1932 by oil baron Henry Clay Folger and his wife, Emily. It contained (and still does) the largest collection of Shakespeare First Folios in the world. At the behest of the Folgers, designer Paul Phillipe Cret included a theater, but it would remain dark for nearly four decades.

The Folger Theatre Group was founded in 1970 by Folger director O.B. Harbison, with its first artistic director, Richmond Crinkley. Attractive and faux-Elizabethan in style, the theater itself had limitations — just 243 seats, impeded sightlines, and limited backstage space. Folger left it in trust to Amherst College and its management to a Board at the university, which was his alma mater.

The first three directors of the new Folger Theatre Group, Richmond Crinkley (1969–73), Louis Scheeder (1973–81), and John Neville-Andrews (1981–86) faced a time of struggle. Crinkley had successful productions but, according to the authors, did not seem particularly interested in Shakespeare. The second, Scheeder, wasn’t either; he produced only two Shakespeares in his first two seasons. Possibly due to pressure from the Board, and to a lagging box office, he turned to Shakespeare, and attendance improved. However, the critical response was disappointing. In 1980, his Charlie and Algernon, based on Daniel Keyes’ science-fiction novel, became a hit and went to Broadway. Despite this success, the Board demanded severe budget cuts, and he resigned. The third, John Neville-Andrews, focused on classics, especially Shakespeare. He formed a 12-person resident company, which included Ed Gero, Floyd King, and Franchelle Stewart Dorn, all of whom would make major contributions when Michael Kahn took over. But his productions had two problems: first, they were expensive, and second, critics did not like them.

In her witty, wide-ranging Foreward, Maureen Dowd calls Shakespeare “an avatar of national identity.” It is tempting to conclude that there was not enough support yet for Shakespeare as an inspirational figure and theatrical lodestar. But suddenly, that changed. Why? Because in an unusually stark example of unintended consequences, the Folger Board moved to close the theater.

This led to what is known as the War of 1985, during which outraged Washingtonians, Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, complainants from all over the country, and many others, united to “save our Shakespeare.” In the end, the Library and the Theatre parted ways, although under the terms of the agreement the new company would still use the playhouse. In May 1986 Neville-Andrews resigned. The new artistic director, Michael Kahn (1986–2019) would lead the theater to a period of astonishing achievement.

Enter Michael Kahn

The Folger, of course, was in financial difficulty. It was the period of Reagan and later George H.W. Bush. Kahn would face a number of challenges in his effort to turn things around.

Kahn’s life up to that point had been immersed in theater. In his interview with Payne, Kahn describes himself as a “bossy” little boy who produced plays in first and second grade. As a student at Columbia, he directed the first American production of Pericles (1960). Kahn relates that after college “my friends and colleagues were young playwrights like Sam Shepard and Jean-Claude Van Itallie and Andy Warhol, who was a young artist at the time. I did a bunch of work off-Broadway, at Caffe Cino and La Mama, productions of writers like [Joe] Orton and [Eugene] Ionesco.”

Three people, Kahn says, were “pivotal” to his career: playwright Edward Albee, who offered him the off-Broadway premiere of Lanford Wilson’s The Rimers of Eldritch (1967); director John Houseman, who mentored him, and recommended him to teach at Juilliard; and the famed artistic director of the Public Theater, Joseph Papp, who asked him to direct Measure for Measure (1966) for Shakespeare in the Park. Starting in 1968, Kahn taught at Juilliard. By the time he got to the Folger, he had been artistic director at the American Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford for ten years, and for the last five also the artistic director at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton.

Kahn began to think about a new way of doing a close reading of Shakespeare’s text, using the same moment-to-moment technique (based on American “method” acting) he would use with a modern play. He says, “I found a way of getting the actors to examine what the text actually means and why those words and no others were on the page.” He also stressed the heightened nature of the language. He brought Liz Smith from Juilliard as the first vocal and text coach for the company. It was all part of his “vision” of “an American classicism in acting.” Three of the first five shows at the Folger — Romeo and Juliet, The Winter’s Tale, and The Witch of Edmonton — were co-produced with the Acting Company, where he was still artistic director.

He developed an exceptional acting company: Ted van Griethuysen, Ed Gero, Emery Battis, Floyd King, Pat Carroll, Franchelle Stewart Dorn, Bradley Whitford, Craig Wallace, and many more. He brought in stars, such as Stacy Keach, Kelly McGillis, Avery Brooks, Andre Braugher, and Brian Bedford.

Kelly McGillis, known for her work in the movies Witness (1985) and Top Gun (1986), played Portia in The Merchant of Venice (1988). She also starred in the 1989 production of Twelfth Night. When Stacy Keach starred in Richard III (1990), theatergoers famously lined up around the block to see the open rehearsal. In 1990, the Folger Library’s scholar-in-residence, Miranda Johnson-Haddad, wrote in Shakespeare Quarterly that the future “of Shakespeare productions in Washington, D.C. looks brighter than ever.”

Kahn felt that Twelfth Night, (1989) with McGillis (a Juilliard graduate), was about “being in a strange place.” So he picked Sri Lanka to highlight the play’s class differences and Malvolio’s snobbery, which in Kahn’s view is racist colonialism. Still, he cautioned, the choice of location must always illuminate something about the play. In the Washington Post, Lloyd Rose called it “a midsummer night’s dream.”

Influenced by Joseph Papp’s theory of “color-blind” casting, Kahn liked to cast actors of color. Franchelle Stewart Dorn received a Helen Hayes Award in 1987 for her performance as Paulina in The Winter’s Tale. Craig Wallace appeared in numerous productions and performed in Godwin’s Lear (2023) as Gloucester. Jeffrey Wright, another company favorite, later appeared on Broadway in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America (1993), in the film Rustin (2023), and on television in Westworld (2016–22). Sabrina LeBeauf of The Cosby Show played Rosalind in As You Like It (1987) and Cordelia in King Lear (1992). The production of Othello (1990) starring Avery Brooks, Braugher, and Dorn (directed by Harold Scott) came at what the authors call “a fraught cultural moment” — the crack epidemic and rising homicide rate in DC. In 1991, Gale Grate, a Black actress, was cast as the lead in Shaw’s Saint Joan by director Sarah Pia Anderson. In the same year, Kahn was named the “Play-Maker” of the year by Washingtonian magazine.

Kahn made strides as well in gender equity. He cast Pat Carroll (another Juilliard graduate) as Falstaff in a re-gendered The Merry Wives of Windsor (1986). “I don’t think art and responsibility to society can be separated,” he told a reporter in 1988. “I don’t think they were separated for Shakespeare. They certainly can’t be separated for any theatre that I’m the head of.”

At the end of his first year, subscriptions had doubled. He improved marketing and fundraising, and overhauled box office procedures. At the end of the 1989 season, the Folger was taking in $150,000 more than expected. A subsidy from the NEA and the University of South Carolina was also a welcome revenue stream. Kahn was hailed as a modern Prospero.

Still, the small size and spatial limitations of the Folger at that time made it challenging for both theater artists and audiences. Kahn began looking for a new space that would give him more opportunity to expand his vision of American Shakespeare. That theater was the Lansburgh.

Golden Days at the Lansburgh

In 1992, the Folger Theatre became the Shakespeare Theatre Company. The company would perform at the new 451-seat Lansburgh Theatre downtown, in a neighborhood still recovering from the riots following Martin Luther King’s death. The years there became, by all accounts, a kind of golden era. Kahn won Best Director at the Helen Hayes for Hamlet (1993); Mother Courage and Her Children (1994) with Pat Carroll; Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 (1995); and Henry VI, Parts 1, 2, and 3 (1997). Kahn’s Love’s Labour’s Lost (2006) was inspired by the Beatles’ trip to India, to satirize all the Brits who went to India to find themselves. Upon the company’s move to the Lansburgh, David Richards of The New York Times wrote, “The Shakespeare Theatre seems positioned as never before to make good on its ambitions to become America’s foremost classical theatre.”

The larger stage of the Lansburgh proved to be a blessing. In his third season, Kahn was able to mount Shakespeare’s War of the Roses history cycle over the next four seasons: Richard II (1993); Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 (1994); Henry V (1995), and Henry VI, Parts 1, 2, and 3 (1995). Lloyd Rose said, “Michael Kahn may one day top his direction of this Henry V, but if he does there’s the danger the roof will blow off the theatre.” (1996). It became possible to produce minor classics such as Oscar Wilde’s A Woman of No Importance (1998), verse dramas such as Friedrich Schiller’s Don Carlos (2000), and Alfred de Musset’s Lorenzaccio (2004). Lesser-known Shakespeare works such as Troilus and Cressida (1992) and King John (1998) were introduced to the DC audience.

Despite its larger size, the Lansburgh was quite intimate, and the acoustics were excellent. Theater was suddenly very popular in the city in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Kahn founded the Shakespeare Theatre Academy for Classical Acting, now directed by Alec Wild, a 12-month intense program to train actors in Shakespeare and the classics. It is still operating today. Kahn’s ReDiscovery Series, which featured free staged readings of minor classics, often led to mainstage productions.

DC is a majority-Black city. The Supreme Court, the President, and Congress are here. Human rights and national issues will always have a critical role in our artistic conversation. This has inspired some of DC’s finest productions, but it has also caused controversy.

In a famous 1996 speech at the Theatre Communications Group, playwright August Wilson decried the racist attitude and practices and coded standards of artistic excellence of regional theaters. “Colorblind” casting, in his view, was “an aberrant idea that has never had any validity other than as a tool of the Cultural Imperialists who view their American culture, rooted in the icons of European culture, as beyond reproach.” He proposed that support be given to Black theaters and cultural institutions.

Kahn, whose theater was dedicated to the ultimate European playwright, may have felt attacked, according to the authors. Although discrimination against actors of color was indeed shameful, he felt that he had championed such actors from the beginning. There were missteps in this area, such as Patrick Stewart’s Othello (1998) with a race-reversed cast, directed by a white female British director, Jude Kelly. Ironically it was a box office hit due to Stewart’s star power, despite much criticism.

The authors believe that during this era Kahn moved on from the “color-blindness” advocated by Joseph Papp to more contemporary “racially conscious” casting. There were significant successes, such as a production of The Oedipus Plays, set in Southern Africa, with WHUT-TV, hosted by Howard University television, as a media partner. Avery Brooks played Oedipus, and recent Juilliard graduate Tracie Thoms was Antigone, with Earle Hyman as Tiresias (2001).

A proud gay man, and a strong advocate for gay rights, Kahn found queer subtexts in Richard II with Richard Thomas (1993) and had a special attachment to the work of Tennessee Williams. At the Lansburgh, he produced Sweet Bird of Youth (1998) with Elizabeth Ashley and Camino Real (2000).

The theater benefited from the “Third Way,” the Clintonian policy of public-private partnership. In the District, PADC Realty Investors, formed in 2004, invested in mixed-use development. The budget grew from $1.2 million in the Folger days to $11 million. Shortly after the move to the Lansburgh, Kahn became the Richard Rodgers director of Juilliard Drama.

The rebound of the economy in the 1990s added to the starry night of the Lansburgh years. STC revitalized the surrounding area, which had been in a troubled state for some time. It even had a new name, Penn Quarter. But Michael Kahn had another dream: to turn STC into the nation’s premier classical company. And he wanted to turn DC into a theater destination like New York or London. For that, he would need another, even larger theater: the Harman.

The Harman: Looking to the future

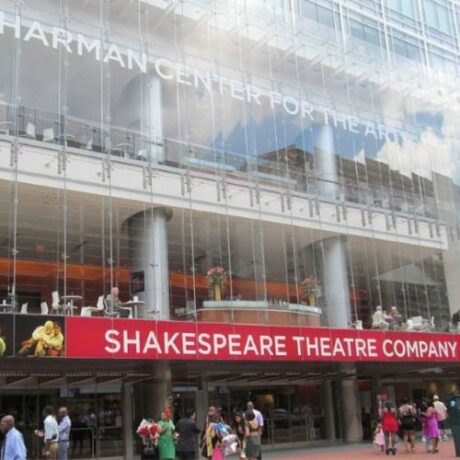

The ribbon-cutting ceremony for the new theater was held in September 2007. It was six stories high and had a large glass atrium. The complex took up half a block. Kahn envisioned the Harman as part of a strategy to elevate DC into the status of a “destination” theater town like New York or London. Despite the Harman’s many successes, the recession put something of a damper on this concept.

It is true that Sidney Harman’s contribution of $20 million was part of the funding, but the DC Council matched his gift. (The final cost was $89 million). Although Kahn had originally wanted an intimate theater, the plans were changed because Harman wanted the building to be a performing arts center. Despite the excitement of the opening, some reviews were mixed.

Charles Isherwood of The New York Times felt that the named plaques such as “The Arlene and Robert Kogod Lobby” conveyed the message that culture belongs first and foremost to the rich. This seems slightly unfair as this practice was common in museums and cultural centers at the time, and still is today. Philip Kennicott, in the Washington Post, felt that the glass facades would induce in onlookers feelings of “envy and desire and appetite.” My guess, however, is that onlookers would be more concerned about their own affairs than the architecture of the buildings around them.

There was a building boom in DC when the Harman was under construction. There was huge growth in Penn Quarter. In his first five seasons at the Harman, Kahn directed Antony and Cleopatra (2007), Richard II (2009), and All’s Well That Ends Well (2010). There were repertories of Julius Caesar and Antony & Cleopatra (2007–08), Richard II and Henry V (2010–11), Schiller’s Wallenstein and Coriolanus (2012–13), and Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 (2013–14). Stacy Keach made an appearance as Falstaff in Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, which was directed in reaction to Newt Gingrich’s Contract with America. In 2014, Moliere’s Tartuffe at the Harman and David Ives’ Metromaniacs were at the Lansburgh, the latter successful, the former not so much. On the other hand, Kahn’s Hamlet (2018) with Michael Urie, and Patrick Page as Claudius, was Kahn’s highest-grossing production at the theater.

Kahn then turned to younger directors — Rebecca Taichman’s Taming of the Shrew (2007), with an interracial romance between Charlayne Woodard’s Katherina and Christopher Innvar’s Petruchio. Taichman also directed The Winter’s Tale (2012) with company members Ted van Griethuysen, Nancy Robinette, and Tom Story. David Muse, now the artistic director of Studio Theatre, directed Julius Caesar (2008), Henry V (2010), and Coriolanus (2013). In 2008, he directed an all-male Romeo and Juliet. His wildly successful King Charles III with Robert Joy was timed to coincide with the 2016 election. In the spring of 2019, he would direct Richard III.

Ethan McSweeney was also a frequent guest director: Major Barbara (2007) and Ion (2008) at the Lansburgh, and at the Harman The Merchant of Venice (2010), Much Ado About Nothing (2011), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2012), The Tempest (2014), and Twelfth Night (2017).

And then there was the matter of the League of Resident Theatres (LORT) Equity, Diversity and Inclusion training (2016) with artEquity. This training is designed to launch, sustain, and engage antiracism in an institution. In Kahn’s view, the need for such training was theater-wide and had to be addressed. Like many other institutions, the theater was mostly run by white men. He views today as a transitional period, when the theater will have to reinvent itself. It will have to, he says, be reinvented by young people with new ideas.

Two young directors received mixed reviews. At the Harman, Ed Sylvanus Iskanker’s “immersive” production of The Taming of the Shrew (2016) was found to be confusing, and Peter Marks found it full of “elaborate distractions.” South-African born Liesl Tommy directed a Macbeth (2017), transformed to North Africa, largely with actors of color, and with white actors David Bishins, Naomi Jacobson, and Tim Getman as the Weird Sisters (actually CIA operatives). Kahn says of the Macbeth, “It took me a while to understand that Liesl, as a South African, was using the concept of the Macbeths to explore the misrule of contemporary South African politics.”

Yaël Farber’s Salome (2015) was one of the highlights of the Women’s Voices Theater Festival. Musicals such as Alan Paul’s Kiss Me, Kate (2016) did well at the Harman, as did his Camelot (2017).

As Peter Marks noted, the Harman era featured some of Kahn’s most adventurous programming. His partnership with David Ives as a playwright — an adaptation of Molière’s The Misanthrope, School for Lies, for example (2017) — was also very successful. Kahn’s tenure ended with the world premiere of Ellen Mclaughlin’s The Oresteia (2019). Although it engendered controversy regarding nontraditional casting and some aspects of the script, it was an engaging and provocative production. In 2019, Kahn retired. In a speech at Georgetown shortly after his retirement, Kahn advocated for the restoration of arts education, which would help young people and lead to a creative blossoming.

Enter Simon Godwin

Simon Godwin was announced as STC’s new artistic director in September of 2018, after an international search. Now an associate director of the National Theatre of London, he was “a veteran of the Royal Court, Royal Shakespeare Company, and Royal National Theatre.” Godwin’s parents were successful literary agents. He studied with Thomas Prattki, former pedagogical director of École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq, which focuses on mime and movement.

Prattki taught him this:

The stakes are high, but also low. For instance, as soon as you say to an actor ‘this better be good’ it will be bad, whereas if you say ‘this might be bad’ it has a chance of being good…. [T]heater has to be rooted. It’s physical. As a director, you are reflected back in your work.

Godwin brought directorial skill, artistic achievement, and transnational professional relationships. But there were some challenges — the theater was running at a deficit and was also in need of a new vision. As he crafted the theater’s future, Godwin credits Michael Kahn with generous support and encouragement.

Godwin’s first production as artistic director was the progressive, playful, and quite enjoyable Everybody (2019) by Black author and MacArthur “Genius” grant recipient Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, directed by Will Davis and presented in the Lansburgh. Gender nonbinary and racially inclusive, it was a modern version of the medieval Everyman. Peter Marks, for whatever reason, was not impressed.

However, popular playwright Lauren Gunderson’s adaptation of J.M. Barrie, Peter Pan and Wendy (2019), was beautifully rendered and well reviewed.

And then there was the pandemic.

Godwin had to cancel the remaining shows of 2019–20, and the entire 2020-21 season. Jose Saramago’s Blindness (2020), adapted by Simon Stephens, was a fascinating exception, and the only live production of the season. It required the audience to listen to Juliet Stevenson’s voice as she narrated the harrowing story of an apocalyptic pandemic. Frightening, original, and strangely moving, it was one of very few theatrical experiences available during the pandemic. In 2020, Godwin directed an online production of All the Devils Are Here (which they certainly are) created by and starring well-known Shakespearean actor Patrick Page. Page’s All the Devils Are Here recently had a run onstage at the Lansburgh, directed by Godwin. It was a masterfully enlightening and transformative experience

In 2021–22 the company re-opened. Our Town (2021), directed by Alan Paul, suffered from COVID outbreaks; understudies went on for nearly every performance. These kinds of absences also plagued Lolita Chakrabarti’s Red Velvet (2022), the story of pioneering Black Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge.

To boost the finances, Godwin launched a fundraising drive called the Phoenix Fund. Still, in July 2020 STC had to lay off some of its staff and cut its 2020–21 budget from $18.5 million to $10.5 million.

Renaissance

In 2021, James Baldwin’s The Amen Corner, directed by Whitney White, was an artistic and commercial landmark. As the authors note, White added a gospel chorus, which added depth and musicality to the story of a Black single mother trying to keep her family together. And to keep her son from the dangers outside. The role of the church in the Black community was front, center, and fascinating. White was to return with the compelling Macbeth in Stride (2023), a musical with strains of pop, rock, gospel, and R&B that examined Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth and the many sides of Black female ambition, rage, humor, and desire.

By fall 2023 the company had come back financially somewhat; the budget was back to $16 million, but the repertory was a combination of co-productions, Broadway tryouts, and international productions. Before the pandemic only one of the six shows was a co-production for a season; next season at least five were.

Once Upon a One More Time (2021), the Britney Spears musical, smashed box office records. However, STC workers said conditions were unsafe, and wages were low. They also cited the 2020 layoffs, which meant that workers were without healthcare coverage in the midst of the pandemic. Consequently, STC production staff joined IATSE Local 22, the local stagehands union. This made everything more expensive.

In 2023–24 there were more co-productions: Evita, co-produced with American Repertory Theatre, and As You Like It (co-produced with Bard on the Beach) featured the music of the Beatles, adapted and directed by Daryl Cloran. The Jungle (2023), co-produced with St. Ann’s Warehouse and Good Chance), and directed by Stephen Daldry and Justin Martin, was an immersive work about a refugee camp during the Syrian war. The entire Harman space was converted into the camp, and the plight of the refugees was electrifying. Some actors were actually from the Middle Eastern and Syrian diaspora. Others were well-known English performers. The audience shared the performance space with the actors, on different types of chairs, benches, or couches.

Godwin’s directing credits at STC include an astonishing number of artistically arresting Shakespearean productions: Comedy of Errors (2024), King Lear (2023), Much Ado About Nothing (2022), Timon of Athens (2020), and the 2024 production of Macbeth with Ralph Fiennes and Indira Varma, which also played in Liverpool, Edinburgh, and London.

One of the strengths of Lichtenberg and Payne’s book is its contrasting portraits of Kahn and Godwin. By highlighting their similarities and differences, the authors deepen our understanding of both. Like Kahn, Godwin utilized star actors, such as Kathryn Hunter in Timon of Athens and noted Shakespearean John Douglas Thompson in the “color-conscious” Merchant of Venice (2022). Godwin starred Patrick Page in a King Lear (2023), which Peter Marks described as “one of the best…maybe the best.” It became the best-selling Shakespearean production in STC history, and established Godwin as a major interpreter of Shakespeare. He began work on Lear, he says, not as a tragedy but as a group of people looking for what they want. You want to see in a classic something people have not seen before, he says. (You can imagine Michael Kahn saying much the same thing.)

Godwin, like Kahn, addressed social and political issues, as in The Jungle and Tom Stoppard’s incandescent Leopoldstadt (2024), about the history of a Jewish family up to and including the Holocaust, directed by Carey Perloff.

As for differences, Kahn’s focus was on ideological and aesthetic principles, while Godwin’s unique talent was his flexibility and gifts for improvisation and problem-solving. Kahn patterned STC after the National and the Royal in Britain, but Godwin’s style is more transnational, combining pop culture with contemporary social and political trends. His programming would be big-budget musicals, family programming, and adaptations of Shakespeare.

Godwin is quick to respond to cultural shifts. It was the time of George Floyd, Black Lives Matter, and the infamous incident of the protests at Lafayette Square. Inspired by the BIPOC letter “We See You, White American Theater” and “Principles for Building Anti-Racist Theatre Systems,” there were new standards for hiring, workplace behavior, and planning.

According to Godwin, since we know that Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Kyd, and Thomas Middleton wrote small parts of Shakespeare plays, we can be more collaborative instead of idealizing the text. This is counter to the American tradition of viewing a Shakespeare play as a kind of sacred document. Maureen Dowd argues that despite the fact that Americans have a certain colonial resistance to the deification of Shakespeare, we are drawn to him nonetheless by a Freudian desire for a father figure. I would add that if Shakespeare is a religion, Americans have something of the zeal of the convert. This collaborative focus has led to remarkable results. Godwin’s productions of Macbeth and King Lear were instant classics. His delightful Much Ado About Nothing showed us that in comedy his work is equally mesmerizing.

Godwin’s international stature has not lessened his openness, empathy, and interest in STC’s ability to engage the local audience. As STC associate director and scholar Dr. Soyica Colbert, Idol Family Professor of African-American studies and performing arts at Georgetown, relates about their first meeting: “He wanted to be in conversation with folks who were part of the D.C. theatre scene from different cultural perspectives, class and race and gender. He seemed really invested in community building.”

As a Brit, what are Godwin’s thoughts on America?

Being a Brit has been helpful, because it’s made it easier for me to ask simple questions. You could say useful naivety is ignorance or even irresponsibility, an unhelpful lack of preparedness. I’m always walking that line! But I’ve tried to be open-hearted. In England, I am steeped in class history. I’ve found the relative classlessness of America liberating. It’s a younger country. This youthfulness causes a huge amount of conflict, but it also provides room for great adventurousness.

Let us hope that America’s “relative classlessness” will continue. Meanwhile, Godwin reminds us of a timeless truth: Classics, he says, can be more of a commentary on the present than plays written today. He quotes the words of Peter Brook, “Hold on tightly, let go lightly.”

One can imagine Michael Kahn saying the same.

About the Wendi Winters Memorial Series: DC Theater Arts has partnered with the Wendi Winters Memorial Foundation to honor the life and work of Wendi Winters, the DC Theater Arts writer who died in the Capital Gazette shooting in Annapolis, Maryland, on June 28, 2018. To honor Wendi’s legacy, the Wendi Winters Memorial Foundation has funded the Wendi Winters Memorial Series, monthly articles to be produced by DC Theater Arts to bring attention to theater companies and theater practitioners in our region who engage in exemplary work that makes our community a better place. The centerpiece of these articles is a series we are calling “The Companies We Keep,” articles offering an in-depth look at one local theater company each month. In these times of division and conflict, DC Theater Arts chooses to celebrate those who do good.

For more information on DC Theater Arts’ Wendi Winters Memorial Series, check out this article graciously published by our friends at District Fray Magazine.