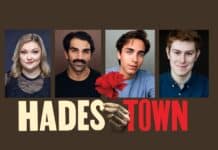

As playwright Bob Bartlett’s Love and Vinyl makes its DC premiere, this play about finding love in a record store in a digital age will perform at a record store, Union Market’s Byrdland Records. It’s about best friends Bogie (James J. Johnson) and Zane (Carlos Saldaña, who also directs), who visit a local record store and meet the “magic” of store owner Sage (Rachel Manteuffel).

DC Theater Arts caught up with Johnson and Manteuffel about the process, their relationships to record stores, and the community-building that comes with site-specific work. Manteuffel originated Sage in Love and Vinyl at KA-CHUNK! Records in Annapolis, Maryland; Johnson portrays Bogie for the first time. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

DC Theater Arts: How did you first become connected with Bob and why did you want to be involved in this production?

James J. Johnson (Bogie): In 2009, he reached out to me to audition for a production of Native Son that he was directing at American Century Theater. I couldn’t do it at the time. But we’ve been trying to work together since then, and this is the perfect blend. I love music, and I don’t go to record stores as much as I used to. I do have a record player and a small collection of vinyl. I was hitting up the stores quite a bit about five years ago. I slowed down, because I was like “Do I need all this stuff?” as we were moving quite a bit. But I still like to listen from time to time. Even before vinyl, I grew up in the ’80s and ’90s, so cassettes and CDs were just such a big part of my life and my identity. Getting the chance to live in that world again, not onstage but in reality, is exciting. In all my life, I’ve been doing shows onstage. To do a show in a real place presents a unique challenge.

Rachel Manteuffel (Sage): Bob and I did this small Maryland company that doesn’t exist anymore called Active Cultures that connected playwrights and actors. And we’d hang out a lot at the Fringe bar, back when there was a Fringe bar, the year he did Barebank Ink. We were friends; we talked about the shows; he said, “I’m gonna write a part for you.” That’s really awesome, obviously. He did. Then he did it again. It’s one of the coolest things that can happen for you, as an actor: Bob Bartlett wants to write a part for you.

What’s your own familiarity with record stores and browsing for records, cassettes, or CDs? Any favorites?

Johnson: Oh my gosh, cassettes. The first one I remember buying was a Philly hip-hop group called Three Times Dope. Then there was Candyman, who had his song called “Knockin’ Boots.” Mariah Carey, her first album, with “Vision of Love.” Even going back further, the first cassette I got, my parents bought Prince’s Purple Rain soundtrack for me when I was nine years old, not knowing what it entailed. That hooked me into Prince.

Manteuffel: My boyfriend is very into ’60s music, so he has a lot more than I do at the moment. I have some Alanis Morissette, the Killers, and the White Stripes. Leonard Cohen is the only one I have bought that is older. One of the great things about records is that every antique shop has some records that are maybe dodgy quality, but you never know what you’re going to get. I think there’s no way to actually be as cool as a record shop. I just feel like everything there is cooler than me, so me getting some of it is cool.

Can you describe your character in this story?

Johnson: Bogie is a fun-loving guy, a creature of habit. He loves a record store. He’s lonely, but has kind of come at peace with his loneliness. But he’s challenged by the presence of this new person, the owner of the record store, and her magic. He’s battling with all those things at his age — at my age, 50. Being open to discovering magic, not being too static and evolving, is what’s interesting to me. I told Bob last night, I’m getting a sense that we’re peering into his soul immensely. This is a very vulnerable piece. I feel like Bogie was me, especially before meeting my partner 16 years ago. I completely relate to this character in ways I don’t know if I related to a character before, outside of anything that I’ve written. People will relate to Bogie, or Zane (played by Carlos), or Sage, the three personalities that they represent.

Manteuffel: A lot of Sage’s magic is how reserved she is. She has this front that a lot of people working in retail have, that you want to seem like you know a lot of things, things matter to you, and this meeting that you’re having with a customer matters to you. But behind that, there’s this protectiveness you have to have. There’s no way you can — at least I couldn’t — let down walls in front of customers every day, all day. There’s the process of chipping away at it, and letting you see the real her. Because some of what she gives seems to be the real her, then that eventually is broken down. I’m not sure she’s any cooler than anyone else once you see that come down. That’s the best part.

How would you describe the experience of listening to records?

Johnson: Back then, when you wanted to hear something specific, you had to work to find it. Whether it was going to the store to buy it, and there’s a chance that it might not be there, or once you actually had it, and you want to listen to song number five, you had to fast forward, if it’s a cassette, through all the other songs, and hopefully you’ll land in the area that you’re looking for, as opposed to, “Let me just click this button and boom, the song is there.” That’s the big difference as someone who comes from cassettes to digital. I don’t miss cassettes as much. I do kinda miss CDs. Vinyl was big, as a format for listening, but it also was physically big. There’s something about flipping with your fingers, the excitement of coming across an album you love or something you hadn’t seen in a while. I was running into singers I hadn’t heard since the ’80s as I was flipping through in the store.

Manteuffel: The last show definitely got me to buy a turntable. Now I have records and am slowly figuring out how they work. It’s actually so much cooler than MP3s, and a lot more expensive, and you have to be more careful. That actually adds to the awesomeness of it. I feel like every time you play a record, the record is changed. There’s a physical process. Thinking about the person making this record, it being physically created, me physically playing it, and the way an album is put together, it feels more like the musician or something of the musician is in the room with you, and that’s amazing.

How does it feel to do this show in an actual record store? What elements of it are being used that maybe you wouldn’t think of?

Johnson: What’s been a revelation is the use of the door. We come in through the front door, where everyone comes through. There’s no real separation of the reality and the stage. We’re there in the midst of the record shop. We’ve been inside the record store for a photo shoot but we haven’t had the chance to stage or play it out in the store, so those elements are what I’m curious and excited about.

What’s the importance of building community in this type of work?

Johnson: To look at the current state of things politically, not knowing exactly what’s in store for mainstream theater…building community with things outside of the box may be a good way to go, for it to survive as a discipline. Bob has already started doing that with laundromats, so he has other ideas. Building community with Byrdland Records, but also other vinyl stores throughout the country, or other venues, so that they can coexist — the worlds of retail, commerce, and the arts — is a possible way for theater to persevere. When we were there doing the photo shoot, customers saw us, and Bob was able to talk about the show. Being there creates a natural curiosity. People there are natural shoppers for vinyl, so it’s like, “Oh, something that’s related to that!” in a space where they’re not used to seeing a play.

Manteuffel: The great thing about record people is they put in the work. They are used to having to do work to find the things that they love. If a record person is intrigued by this, they’re going to show up. Theater people are the same way, but in different circles. Record people and theater people coming to the show is a cool way to build community. I know one person who was a regular at KA-CHUNK!, saw a poster, and was like “Hey, look at this play you’re in!” I was like, “Oh, I know!” ’Cause it’s just such a different world. Also, he goes to Annapolis to look for records. When you love something like how record people love records, you’re willing to put in the work.

Rachel, after playing Sage at KA-CHUNK!, what has changed or expanded, and how is that affecting your performance?

Manteuffel: It sounds like there will be a lot more people in the audience. Having more people there opens it up. It was a small space at KA-CHUNK!, so it was more like a conversation. Opening it up, the playing of it will have to be bigger, which is a nice challenge, because it is a very intimate play. Also, there tend to be more people in Union Market, lots of passersby in a way that maybe wasn’t true on Maryland Avenue.

A big challenge: you don’t get a lot of time to rehearse in the space. One problem last time was that I am not actually familiar with record playing and I have to do it. I didn’t get much chance to practice on it. 60% of the audience is going to know exactly how it looks. If I screw it up, it’s like “She doesn’t own a record store.” It’s stuff you find out when it happens. We had all this blocking last time, and then it turned out you couldn’t really move around much in that space, but now we can! Unless once there are people, they take more space. A lot will be figured out with the audience, which is exciting but also daunting.

What has Carlos being a returning performer and directing added, and what’s it been like introducing JJ to the process?

Johnson: There’s something nice about having someone whose mind is surrounding the piece in various ways. It’s nice to be welcomed by them and them having the comfort of doing it before. I need people who are confident. I get to reap the benefits of their lessons.

Manteuffel: It’s like discovering the play again. Sage has this speech about how people leave their dead loved ones’ records at the store for her to deal with. Her big emotional connection is to her mother’s records. The implication is that her mother’s dead. So her mother’s record she plays at the end is a dead person’s record. It was something Bob, Carlos, and I hadn’t noticed, but somehow with JJ in the room, we all went “Oh! This is brilliant!”

How do you hope audiences walk away from this production feeling? What are the biggest takeaways?

Manteuffel: It’s something my character says: this is a sacred space, the record store. Beyond an individual’s feelings about music and listening to a song, there is something about being in this place that is dedicated to putting in the work. It requires more of you to visit a record store, to see them there, to get the right machine to play it, and to take care of the records. It’s irreplaceable. It’s something you can’t get any other way than doing it.

It’s been very cool for me, because I hadn’t been like that at all, to be let into that world that can take over people’s lives, in a good way. I hope the audience can do that too: get a backstage pass into the love of records, see something that usually takes years to learn about, see people who are in that space and how they operate in it and absorb it. It’s the feeling of going to a record shop and feeling like you can belong there. Like, you know what its secrets are.

Love and Vinyl will play from February 13 to March 9, 2025 (Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays at 8:30 PM), at Byrdland Records, 1264 5th Street NE, Washington, DC. Love and Vinyl runs 85 minutes with no intermission. Because of the uniqueness of the venue/performance space, the production seats only 30 guests per performance. Audience seating is provided. No late seating. Tickets ($35 plus taxes and venue processing fee) are available here.