By Sam Berit

The only way I can make sense of the severe moment we find ourselves in is to see it as a story that’s been told before. In history and art, there are many stories that align with the present — but there’s one that feels personally important to consider now. It’s a musical that addresses desire, as many do, but further explores the act of desiring itself — of wishing. Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s 1987 musical Into the Woods depicts humankind’s most persistent and cyclical qualities and consequences.

Into the Woods is a show of familiar fairy tales — notably Cinderella, Rapunzel, Little Red Riding Hood, and Jack and the Beanstalk: weaving famous plot points together to create a new story centering an invented Baker and Baker’s Wife duo. Act I begins with a sprawling opening number listing the goal of each character’s journey: “Into the woods to sell the cow/Into the woods to get the money/Into the woods to lift the spell/To make the potion/To go to the Festival/Into the woods to grandmother’s house….” Despite the varied goals listed in the song, the line “I wish…” reverberates from character to character as a constant ringing. They all long to improve their lives through their quests in the woods. This longing remains evident throughout Act I, which ends soon enough in a neat braid of success: Cinderella and Rapunzel both with their respective princes and free from their oppressive homes, Little Red reunited with her grandmother and avenged through skinning the Wolf who tried to eat her, Jack and his mother rich with gold — the giant he stole from now dead in his own backyard — and the Baker and Baker’s Wife expecting a child after undoing a curse of infertility. The characters’ journeys converge in the woods and separate again once their wishes come true.

Into the Woods is a show of familiar fairy tales — notably Cinderella, Rapunzel, Little Red Riding Hood, and Jack and the Beanstalk: weaving famous plot points together to create a new story centering an invented Baker and Baker’s Wife duo. Act I begins with a sprawling opening number listing the goal of each character’s journey: “Into the woods to sell the cow/Into the woods to get the money/Into the woods to lift the spell/To make the potion/To go to the Festival/Into the woods to grandmother’s house….” Despite the varied goals listed in the song, the line “I wish…” reverberates from character to character as a constant ringing. They all long to improve their lives through their quests in the woods. This longing remains evident throughout Act I, which ends soon enough in a neat braid of success: Cinderella and Rapunzel both with their respective princes and free from their oppressive homes, Little Red reunited with her grandmother and avenged through skinning the Wolf who tried to eat her, Jack and his mother rich with gold — the giant he stole from now dead in his own backyard — and the Baker and Baker’s Wife expecting a child after undoing a curse of infertility. The characters’ journeys converge in the woods and separate again once their wishes come true.

Unlike many a theater fanatic, I discovered my love for musicals a little later in life. I was 24 — no need to be dramatic. But I was certainly no buzzing theater kid. I saw a clip online of Broadway performers singing “Sunday” from Sunday in the Park with George in Times Square to honor the show’s composer and lyricist, Stephen Sondheim, just days after his passing in November 2021 — and a new religion took shape for me. Sondheim’s legacy quickly became a pillar of my life and I devoted much of my free time to watching old performances, reading up on his personal history, and listening to select cast albums as prayer. All this to say, I went to see the national tour of Into the Woods in 2023 at the Kennedy Center.

The Kennedy Center, grand like a grandparent, looms large in the nation’s capital as a historic venue for the performing arts. First conceptualized in 1955 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the institution was intended to put the United States on the world’s cultural stage. After the signing of the National Cultural Center Act and years of fundraising under successive administrations, the much-anticipated site opened its doors to the public in 1971 — not only as an artistic mecca but also as a living memorial to one of the building’s greatest champions, President John F. Kennedy. Since its opening, the center has hosted countless events and performances, attracting over two million visitors annually. It also boasts three volunteer programs, all dedicated to supporting the arts.

I saw Into the Woods at the Kennedy Center prior to becoming a volunteer there. It was my first time stepping foot in the hallowed halls, and I wore my best clothes for the evening. There is no more esteemed occasion than attending a Sondheim show at the Kennedy Center — a pinnacle theatrical experience certainly by my measure. I went into the show already knowing most every word.

Sondheim faced criticism throughout his career, especially early on, for writing music that seemed cold and cerebral — unlikely to linger in the ears of the audience after the show ended. In a lyric from his 1981 musical Merrily We Roll Along, Sondheim pokes fun at this criticism through a bloodless producer character offering songwriting advice to two eager musicians: “There’s not a tune you can hum…Why can’t you throw ’em a crumb?/What’s wrong with letting ’em tap their toes a bit?” I’m always baffled when I consider this pushback against Sondheim, mainly because I find that his words dependably reappear in my mind when emotions are heightened.

While lyrics like “No one acts alone/Careful, no one is alone/People make mistakes/Fathers,/Mothers,/People make mistakes/Holding to their own/Thinking they’re alone” bring tears to my eyes as an audience member in the Kennedy Center’s Opera House, they bring solace at home — offering guidance in uncertain times. When Donald Trump won the presidency for the second time, “No One Is Alone” came to mind. The song features toward the end of Act II of Into the Woods. The fulfilled wishes in Act I do not bring lasting satisfaction, and the second act commences with a new prologue that mirrors the first, complete with varied goals and the recurring line “I wish…” punctuating the number yet again. Desire did not end at intermission. As the wishes multiply, danger moves in lockstep — beginning with a tip-toe in the first act and thudding down with the stomp of a scorned giant’s foot in the second. The band of characters must reunite in the woods, a collective goal: taking down another giant.

I began volunteering at the Kennedy Center at the start of 2025 with hopes of cultivating a community of my own. In that first month, I helped conduct sessions for children to get hands-on experience with orchestral instruments and assisted singers auditioning for the Washington National Opera. Given how rewarding these experiences were, I jumped at the chance to help with a post-show activity for the National Ballet of China’s performance of Chinese New Year (A Ballet in Two Acts).

I took the bus and arrived early, giving me plenty of time to pace the iconic Grand Foyer I was now relatively familiar with. The height of the hall immediately conveys the building’s renowned grandeur, while the red velvety carpeting and long Orrefors crystal chandeliers drive the notion home. On one lap, I noticed a quote next to the large bust of JFK that I’d either never seen before or never given much thought to: “The life of the arts, far from being an interruption, a distraction, in the life of a nation, is very close to the center of a nation’s purpose…and is a test of the quality of a nation’s civilization.” There’s something about fine words hitting you on the right day, at the right moment. I believe it’s why you go to church or listen to the same song throughout different stages of your life — it’s not quite that you’re learning something new, but rather that you’re widening the well for more of the message to flow through you. That was my experience on this day, reading the words written years prior to the building’s opening and taking them in at the right moment. Only then did the fragility of the day set in.

I was given a free ticket to watch the ballet and made use of my time shifting my focus from the show to the audience. The ballet itself was hypnotic and more familiar than I anticipated, as it was set to Tchaikovsky’s famed Nutcracker score. The crowd was diverse, with people of all ages sporting a variety of attire — from sweaters to cheongsams. I took in the experience with great care. Just before the curtain call, I darted out to begin the activity.

I was handing out stickers of the different Chinese zodiac signs to exiting audience members, so it was a pretty sweet deal for a free ticket. People with wide smiles swarmed the table I was standing at and sifted through baskets, one calling out “Does anyone have a pig?!” in hopes of finding the sticker that aligned with their birth year. Given this enthusiastic overtaking, I willingly stepped back to allow for a more independent sticker search and began to take in what was behind me.

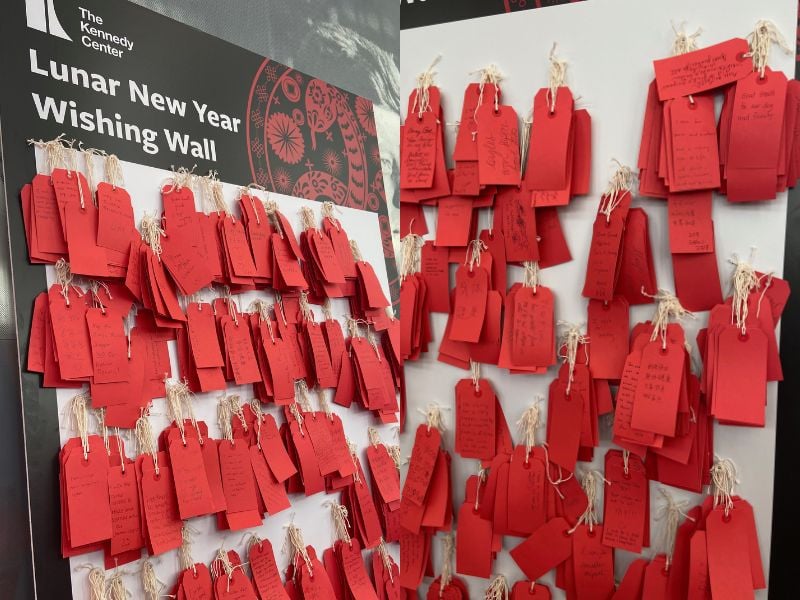

I turned to face the Lunar New Year Wishing Wall — covered completely in rows of red tags, reminiscent of the red envelopes traditionally given out during the holiday. There, in black ink, in different languages, in scrawled and neat handwriting alike, were the simple truths of humankind strung together on display: “I wish for stability”; “I wish for good health and joy for my family”; “Productive and healthy year”; “I wish my friends and family health”; “I wish for good health, luck, and happiness. I also want a cat”; “Health, happiness, chill”; “Health, happiness, and positive leadership”; “I hope peace, justice, and hope are restored to this country”; “I wish for career success and peace and safety within our communities”; “Peace on Earth”; “I wish for world peace and for everyone to be happy no matter what! I also wish for everyone to love and respect others because happiness is our only true destiny!”

Our first-instinct wishes are often, at the core, quite basic. I believe that when given a pen and paper, most people would write incredibly similar hopes for a new year: good health, financial security, and peace — not just for themselves but also for their loved ones and potentially even all people. And despite knowing this on some level, I was overcome with emotion during my head-on confrontation with the Wishing Wall. Not because I was learning anything new about the human condition, but because I was meeting the moment. These wishes, this plain yearning for a good life, seem so dissonant against the time we live in. At this point, so much was already hanging in the balance: Freezes on humanitarian aid, censorship of public health information, and threats to federal workers made up only a fraction of the news. And yet, just miles from where these sparks of horror were igniting, here were those tags scripting for a different reality.

The characters who actively wish in Into the Woods are not all plainly good. They may all be victims of circumstance, but by no means are they portrayed as wholly virtuous figures. They pursue their initial goals through deception, theft, and violence in hopes of changing their lives for the better. The second giant haunts the second act because Jack inadvertently killed the first, too spellbound by the exorbitant riches of the world above the clouds — a world he never knew before. When the characters are summoned back to the woods, they do not initially form a unified front despite now sharing a collective goal. They argue and barter each other’s lives and get easily distracted, often leading to the needless deaths of many at the hands of the second giant. As grief surfaces for the Baker who loses his wife, he sings a song of cynicism called “No More”: “No more giants/Waging war/Can’t we just pursue our lives/With our children and our wives?/Till that happier day arrives,/How do you ignore/All the witches,/All the curses,/All the wolves, all the lies,/The false hopes, the goodbyes,/The reverses,/All the wondering what even worse is still in store?/All the children…/All the giants…/No more”. This song has come to mind a lot in recent weeks. It’s a song that explores the depth of the Baker’s despair and his closeness to abandoning the narrative altogether — and yet still manages to be all about wishing.

I think many of us are currently on a losing team, whether we all realize it or not. We’re losing access to information, access to healthcare, jobs, coworkers, allies, loved ones — and somehow, our wishes never abandon us. Although, we often misguide this desire. Some rationalize the upheaval of good in the world simply because they can’t resist the urge to wish for a different way of living altogether, full of possibility. Others succumb to wearing the veil of apathy to shield themselves from the pain of their own unmet or even unconscious wishes. And many fight on, their wishes bright against darkness — unwavering in their vision of better days. In this way, we all sing the sorrowful song of “No More” and find a way to articulate a dream, some dream, through our times of defeat.

Trouble arises when greed parades as hope. When President Trump, a week after the ballet, announced his plans to terminate members from the Kennedy Center’s board of trustees and appoint himself as the chair, all the memories I have of this institution crystallized into a message: this was — and remains — a moment in time where those who lead a simple life wish for simple solutions, while those who lead a life of excess don’t wish at all — they merely take. That is the point of division, the marker that differentiates us. It’s when those who ascend their goals of wealth and power refuse to reach contentment but instead rage forward, theatrically ripping flowers from the earth to demonstrate they can have power over something beautiful. However, despite their shared prevalence throughout history, the act of taking and the act of wishing could not be more different from each other. This is because the act of taking lacks the true, enduring quality of humanity: hope.

It takes hope to try and revise a story where the ending will always remain unclear. Given enough privilege and power, we all could abandon revision for deletion — erasing all that challenges us. We all could become takers. Clearly, humankind has the capacity to bend that way. But most of us don’t. Most of us write our goals, see our shows, and humbly reach for the lives we want, the lives we may well deserve — and we find greater success or salvation alongside each other. Eventually, the Baker finds his way back to the few characters still alive. They come together, take down the second giant, and reconcile with all they’ve lost. The musical concludes on that pivotal line again, shouted at the end of the final number: “I wish…”. That’s all we can know of what happens after the curtain falls — that those who survived will go on…wishing.

Sam Berit is a writer and theater enthusiast based in Washington, DC.She studied Media and Production at Temple University, pursuing screenwriting. She is always seeking out opportunities to learn more about Sondheim’s work.

Sam Berit is a writer and theater enthusiast based in Washington, DC.She studied Media and Production at Temple University, pursuing screenwriting. She is always seeking out opportunities to learn more about Sondheim’s work.