BOOK REVIEW

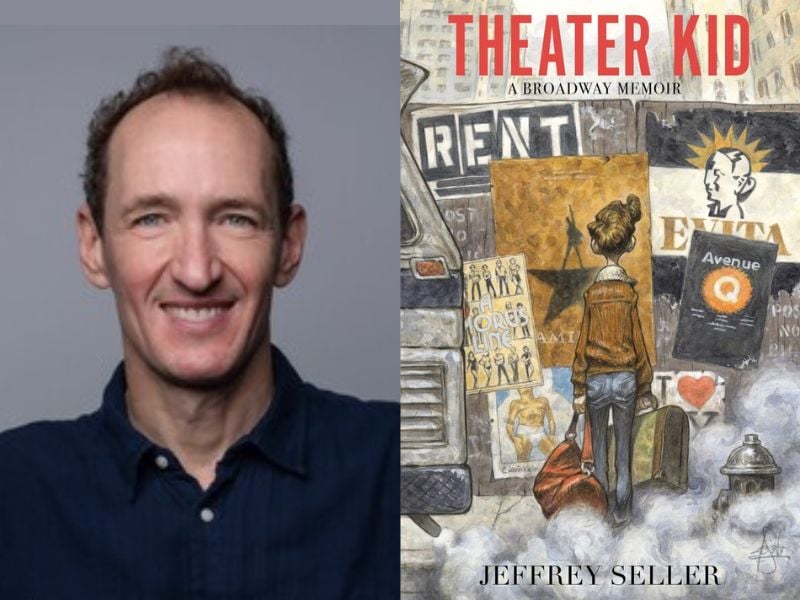

Theater Kid: A Broadway Memoir

by Jeffrey Seller

Simon & Schuster, 2025

I remember when the phrase “theater kid” became an insult. It was back in 2013, when former theater kid and Broadway alumna Anne Hathaway was campaigning for an Oscar for her performance as Fantine in the film version of Les Misérables. Since then, the term has become shorthand for excessive enthusiasm and earnestness.

Search for “theater kid” on YouTube these days and you find a video that asks, “Why are theater kids so cringe?” Over on Reddit, a typical thread begins with a slash to the jugular vein worthy of Sweeney Todd: “Theater kids are some of the most annoying people you will ever meet, no matter what age.”

So I thought Andrew Garfield was rather brave when he proudly self-applied the sobriquet in an interview with Vanity Fair, telling the magazine that as a child, theater “saved my life.”

Jeffrey Seller, one of the masterminds behind the Tony Award–winning musicals Rent, Avenue Q, In the Heights, and Hamilton, and the only producer to have mounted two Pulitzer Prize–winning musicals, doesn’t make that claim as flatly in his new memoir, Theater Kid, but it’s clear from the circumstances of his hardscrabble childhood in suburban Detroit that theater — specifically musical theater — saved his life, too.

In that sense, Seller’s book bears a strong resemblance to Act One, Moss Hart’s memoir of growing up poor and ashamed in the Bronx and rescuing his family from poverty after the triumphant Broadway opening of his 1936 play, You Can’t Take It with You.

Seller, we learn, was a shy, bookish, adopted, gay teen, who stuck out conspicuously in his family, which for the first 100 pages of this book is constantly threatening to unravel due to the outrageous behavior of Seller’s father, an opera buffa character who resembles a “Jewish Paul Bunyan” and works as a part time children’s clown when he is not missing car payments, bedding other men’s wives, or stealing food from a baby.

As a high school student, Seller watches the 1980 Tony Awards on TV, where he “escape[s] into another world” watching Patti LuPone and Mandy Patinkin sing a duet from the new Andrew Lloyd Webber/Tim Rice musical Evita, which “pricks his ears in wholly new ways” and leaves him transfixed. He buys the double cast album and memorizes every word.

Seller’s talent as a producer quickly emerges. While working for a youth theater troupe in high school, he convinces the board of directors to ditch Punch and Judy–style puppet shows for more substantial fare with good parts for children.

Later, while working as a drama counselor at a summer camp in Michigan after his freshman year of college, he implores a troupe of distracted ninth grade thespians to block out all the external forces that threaten to interfere with their performances — sibling rivalries, parental divorces — so they can put on the best show possible of Aesop’s Fables.

His supervisors bristle at his sternness, but Seller insists that the students aim higher. Theater, he says, “gives them the chance to make something. It’s not easy, it demands creativity and commitment.” The phrase “Can we do better?” becomes his mantra.

It’s a question that Seller will continually ask himself and his collaborators, who will eventually include Jonathan Larson and Lin-Manuel Miranda, once he moves to New York City following his graduation from the University of Michigan and launches his career as a producer after an unsatisfying start as a theatrical booking agent.

We are fully halfway through this 368-page book when he meets Larson after an assistant urges him to attend a “rock monologue” called Boho Days by the lanky 30-year-old composer who longs to break into the theater and ditch his day job waiting tables in SoHo. The idea of a “rock monologue” intrigues him.

Larson’s songs, Seller writes, “make the hair on my arms stand up, make me laugh and cry, fill me with awe and hope.” Larson’s autobiographical musical, about a theater kid who yearns to make it in New York, feels like Seller’s life. The next day, Seller writes him a handwritten letter, earnestly making his case for why Larson should take a chance on him as a producer.

The direct approach works.

Two weeks later, Seller is fired from his theatrical booker job and the path before him is clear. He and Larson meet, hit it off, and convince each other that they are just the sort of young strivers who can shake late 1980s Broadway out of its creative slump and revolutionize the art form with true-to-life characters and genuine emotion. Phantom is the biggest show on Broadway, but the spectacle doesn’t speak to them.

“Those aren’t our stories, those aren’t our characters, that’s not our music. I’m making musicals for our generation,” Larson tells him.

When Larson says he is contemplating making a modern-day La Bohème set in the East Village, “a show about people living with AIDS and not dying from AIDS,” Seller, 30, realizes this is their shot.

Now comes the best section of the book, as Seller shows us how a new musical is produced bit by bit, link by link, drink by drink. “Art isn’t easy,” as Sondheim famously said, and Seller and Larson work incredibly hard to bring their latter-day La Bohème to life, laboring over lyrics, changing focus, cutting characters, scrapping songs, and adding new songs.

Rent starts out with a reading at the New York Theatre Workshop in March 1993, and although the opening number “slams like a jolt of energy,” Seller finds that the energy dwindles, and he can’t latch on to any character or find the plot.

Over hamburgers, he offers Larson a straightforward assessment: Stop writing a collage and tell the story of La Bohème, with a beginning, middle and end.

“I’m going to do this,” Larson tells him. “You’ll see.”

Real life tragedy right out of a Puccini opera strikes when Larson suddenly dies of an undiagnosed aortic dissection in 1996 after the musical’s final dress rehearsal before its off-Broadway opening.

I’ll confess that Rent has always left me as cold as a Paris attic flat in the 1830s, but it’s a testament to Seller’s gifts as a storyteller that I was wiping away tears as he describes how the first preview became a sing-through of the musical in Larson’s memory.

Seller and his producing partner Kevin McCollum would later bring Rent to Broadway, where it would go on to earn 10 Tony nominations and win four, including Best Musical, Best Score, and Best Book for Larson. In the process, the pair would also work to democratize theatergoing by introducing the first Broadway rush ticket policy and lottery ticket policy.

In the summer of 2003, a group of guys from Wesleyan University were developing a new musical called In the Heights, and McCollum showed up to a draft presentation at a small theater on 42nd Street. Seller is honest enough to admit his mistake in declining to attend that fateful evening; he might have tried to take credit for being the first to discover the musical’s now-famous creator, Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Unfortunately, having given over so much of his memoir to his early childhood, Seller doesn’t have much space left to describe his partnership with Miranda, for whom he produced In the Heights and the mega musical Hamilton.

But I am grateful for the scene in which Seller describes his initial reaction to the song “96,000” from In the Heights. “How did a twenty-four-year-old composer understand the life experience of a seventy-five-year-old woman? This was the first time I wondered if Lin’s gift was divine.”

I have sometimes wondered the same about Stephen Sondheim, and once Seller raises the stakes that high, I craved more philosophical musings from him on the value and import of musical theater.

Great musicals like West Side Story and Fiddler on the Roof “enriched our culture, our civility, our community,” he writes. I wanted to hear more about what his musicals did to change us for the better. On the last page of his memoir, Seller argues that Rent did accomplish what Jonathan Larson set out to do, “create a Broadway that was about our characters, our stories, our music.”

And maybe that’s enough.