Call it a fictionalized autobiography — or a memory play, if you will — The Berlin Diaries, extended through June 29 in its regional premiere at Theater J, is the story of the author’s search for a secret that lay hidden for more than 80 years.

It’s a Holocaust tale — told in its original form by the playwright’s great-grandfather, who buried the truth in order to spare his children and grandchildren from the knowledge of a terrible loss. In the play, facts that were deliberately omitted have been resurrected.

Curious to know why and how the play came about, I talked to Andrea Stolowitz, the multi-award-winning playwright, over a video link from her home in Portland, Oregon, where she lives with her husband, an East German–born physics professor at Reed College. Our interview was sandwiched between her older son’s college graduation and a trip to Ireland, where she is now working on a new play commissioned by the Abbey Theatre.

Berlin Diaries begins in Durham, North Carolina, in 2006. A letter has arrived from the U.S. Holocaust Museum, announcing that the playwright’s great-grandfather’s diary, which she has long refused to read, has been donated to the museum.

The letter informs Stolowitz that — in return for this donation — she will be getting glossy copies of the diary, which was written in 1939 and addressed to her mother’s generation. The diary describes his life in Germany, how he left the country, and his subsequent life in the United States.

Stolowitz, played by Dina Thomas, looks at the diary and finds it impossible to read. It is written in the tiniest script you’ve ever seen.

“Who reads script anymore?” she asks. She puts it on a shelf and — though she takes it wherever she moves — she never opens it again until she is about to go to Berlin for one of her husband’s sabbaticals. At that point, she thinks, “Maybe this diary will have the makings of a good play.” In the past, she had never wanted to read it because she didn’t want to deal with the Holocaust.

“It’s like enough already,” she told me. “But then I realized that this is not a diary about the Holocaust. There is nothing about the Holocaust in it. It’s about family history and a lot of other things. So I decided that I would make it the basis for a new play. I managed to read seven pages of the document, wrote a proposal, got funding, and then moved to Berlin with my husband. (He’s not in the play, it’s just me, since there’s only so much room on the stage.)”

But then — in both real life and the play — she gets to Berlin and sits down and actually reads the diary, and realizes it is extremely complicated and there’s nothing in it that would lend itself to a play. She is horrified.

“I practically lose my mind because I have promised this arts organization that I would write a new play, and they have given me money to do it. So I have to do something. And so I begin to think about the time that he was writing this diary, from 1939 to 1948. And I realize that what he’s written is a children’s book. A nice book for nice children. There’s nothing about the Holocaust because, when he starts writing, it hasn’t happened yet.

“He arrives in the U.S. in 1936. By 1939, his daughters are here too. They’re having babies. He begins writing this on the first of January 1939, to give his grandchildren details of his life in Germany. He’s telling them where he is from, his family background, and who he is, because they’ll never know anything about that other world. They will grow up here, in the United States.

“When he starts the diary, Germany has not yet invaded Poland. So yes, there is antisemitism. And yes, Hitler’s in power. But nothing else has happened. And as he’s writing this book, he’s trying to figure out how to report both past and present. But a lot is hidden. He’s not saying things because he’s writing to children.

“So I use the diary to try to uncover what he would have known, what he could have known, about what did happen to his family. And so I become the first person in my entire family to know that we had 21 first cousins who were killed or rounded up in Berlin and sent to death camps. We didn’t know this. His myth was that everyone made it out alive. In our immediate family, they did. In the rest of the family, they did not.

“So the play is about my discovery of the past, my reconciliation with it, and my reconciliation with my own family. In doing so,” she concluded, “I set out to change some of the things that needed to be changed.”

Her great-grandfather left Germany in 1936. His first daughter left two years earlier, in 1934. She had been studying medicine in Freiberg and was no longer allowed to continue her studies because she was Jewish. It was the beginning of a series of repressive laws, preventing Jews from entering the professions or from studying at “Aryan-only” schools.

At the time, he was a doctor in Berlin, but under Nazi law, he could no longer earn a living. Luckily, he left early enough to get out, and to be able to work as a doctor in the U.S.

He was a writer as well, though not professional. He wrote poems, stories, and songs. “I think writing is a Jewish trait, part of keeping memory alive,” Stolowitz said, adding, “that’s just my theory” and acknowledging that many other faiths share the same proclivity.

“The play is a memoir,” she explained. “And the way I report it is how I experienced it when I searched for the truth in Berlin. Is it the truth? No, because everything that happens in the play is filtered through my personal lens.”

However, in writing the play, she did set some rules for herself. “I never changed the diary itself. However, I did move portions. For example, sometimes, in the diary, he has an idea, and then he spends five pages explaining it. But all I really needed was the idea. I didn’t need the interstitial stuff. So what I allowed myself to do in the diary was to use certain sections but remove others. Some of it is written in German, which an American audience might not understand. So I translated some things, or just omitted the German.”

“But the diary itself is intact,” she averred. “I didn’t add anything, but I did remove sections and words for clarity.”

In fact, she explained, she couldn’t fictionalize any of the diary, since that would amount to Holocaust denial. “This diary is an actual book that sits in the Holocaust Museum. So if I were to start making up stuff about the Holocaust, that would open the door to people who say, ‘Well, look, if this isn’t true, then that isn’t true. And so I’ve been very careful in this play to remember that the tool of Holocaust deniers is any misrepresentation of the Holocaust.”

Stolowitz never knew her great-grandfather, since he died in 1949. She was born in 1972.

“I’m 53,” she laughed, describing it as a liberating age. “You don’t care anymore what people think,” she explained, counting the ways in which turning 50 is a freeing experience. “Nobody looks at you as a sex object. Your children still need you, but not in the same way. And you’ve been alive for so long that you can’t really get excited about things. And if you’re still healthy, as I am, it’s perfect.”

Another liberating aspect of her current life is the freedom from teaching, which leaves a lot more time for playwriting. She just quit this year, after teaching full-time since 2003. She began her teaching career at Duke University in North Carolina — where the play begins — then moved west to UC-San Diego, where she got her MFA. Her final stop was at Willamette University in Oregon, where she taught playwriting and screenwriting for film and TV.

“I left Willamette this year because I received a fellowship from a foundation that gave me $25,000 — the same amount that I had made as an adjunct professor — and they said they couldn’t hold my position if I left for a year. So I said, ‘Okay, I guess I’ll leave.’ And so now I no longer teach. My husband is still on the faculty at Reed, which is good, since somebody in the family has to have a regular salary.”

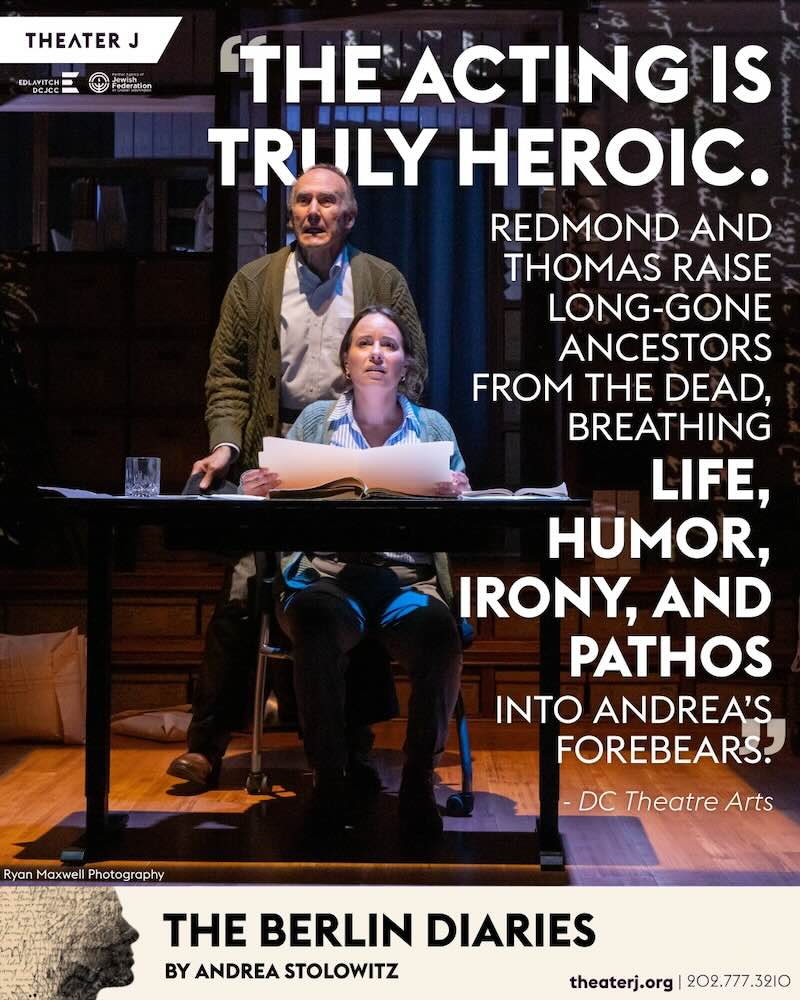

The play itself, according to Stolowitz, is a little different from most because of the way it’s designed. There are just two performers, portraying 14 characters. The two are Lawrence Redmond and Dina Thomas, both well-known and admired for their work on the DC stage. Directing the play is Elizabeth Dinkova, artistic director of DC’s Spooky Action Theater.

The Berlin Diaries has had several lives, beginning with a two-act version that was produced in Berlin and Oregon before going on tour in Canada. At the time, Stolowitz was working on a shortened version, aiming for its opening in New York in 2019.

The Berlin Diaries has had several lives, beginning with a two-act version that was produced in Berlin and Oregon before going on tour in Canada. At the time, Stolowitz was working on a shortened version, aiming for its opening in New York in 2019.

“The two-act productions were like out-of-town tryouts,” Stolowitz said. “I realized the play was too long, so I wrote the current version, which is one act. But then the pandemic came, shutting down the theaters. When we finally opened in New York, it was 2023.” The theater was 59E59, a small, nonprofit venue adored by serious New York theatergoers.

Following that run, the play was picked up by the National New Play Network for a Rolling World Premiere. Due to Equity rules, the 59E59 premiere was not included, nor were other productions, including one in Chicago and the other here at Theater J.

While many of her plays have Jewish characters, she did not realize until recently that the plays themselves were Jewish. For example, her first play, Knowing Cairo, which was produced in 2003, was about old age and how we, as a society, care for the aged. “It was not until I wrote Berlin Diaries that I understood that the fact that the character was a Holocaust survivor — like my great-grandfather — had a lot to do with what happened in the play.

“I now recognize that Cairo is a very Jewish story, as is Berlin Diaries and the new play that I’m working on in Ireland. In fact, the Irish play owes its existence to this one,” she said.

What happened was that the Abbey Theatre, Ireland’s national theater in Dublin, liked The Berlin Diaries but didn’t want to produce it. Instead, they proposed a play about the remnants of what was once a thriving Jewish community in County Cork, detailing its recent history, what it’s like now — with just two thousand Jews left — and its hopes for the future.

“It raises questions that face worldwide Judaism today,” she said, adding that the project began before October 7 and is now quite different from what she envisioned at that time.

In addition to the Irish play, she has several other productions in the works. One is an opera libretto, called The Limit of the Sun. “We’ve had the workshops, and now we’re waiting for an opera company to take it over,” she sighed. “It’s about a U.S. journalist who’s been kidnapped and is being held hostage. The other characters include the handler, the journalist’s mother, and an FBI agent. It’s based on a true story, and it’s about international justice and who is tasked with upholding it. It’s also,” she added, “about mothers and children.”

Berlin Diaries is her eighth play to be produced, though she has dozens more in development or commissioned.

Stolowitz grew up in Riverdale, a leafy oasis located improbably in New York City, just north of Manhattan, and went to the Horace Mann School and then Barnard College. After Barnard, she moved to Berlin, then returned for graduate school in California, followed by marriage, family, and teaching at Duke in North Carolina.

Asked why theatergoers should rush to see the play before it closes next week, Stolowitz agreed that the rise in antisemitism — along with the return of autocratic rule — makes the Holocaust more relevant than ever. “The question, “ she asked rhetorically, “is how do we, as third- or fourth-generation survivors, move on, while making sure that the Holocaust itself is not forgotten.”

The first generation of survivors is nearly all gone, though their descendants live on, still trying to piece together the puzzle of how it happened and whether it could, given the circumstances arising today, happen again.

EXTENDED: The Berlin Diaries plays through June 29, 2025, presented by Theater J at the Aaron & Cecile Goldman Theater in the Edlavitch DC Jewish Community Center, 1529 16th Street NW, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets ($70–$80, with member, student and military discounts available) online, by calling the ticket office at 202-777-3210, or by email (theaterj@theaterj.org).

Running Time: 90 minutes with no intermission

The program for The Berlin Diaries is online here.

SEE ALSO:

In ‘Berlin Diaries’ at Theater J, an absorbing remembrance of lost family (review by Amy Kotkin, June 11, 2025)